Panama Papers And Bank Secrecy: Impact Of Blacklisting – Analysis

By VoxEU.org

The revelations in the Panama Papers have highlighted the role that banking secrecy plays in the global economy. In the absence of strong legal instruments to prevent and combat banking secrecy, soft law practices such as blacklisting have been introduced in the hope that a stigma effect will lead to a reduction in illegal international capital flows. This column argues against the existence of a stigma effect, suggesting that the demand for and supply of banking secrecy are likely to be relevant for a long time to come.

By Donato Masciandaro*

On April 2016 revelations in the Panama Papers spotlighted the role that banking secrecy performs in the global economy. The facts have caused increasing concern that banking secrecy lies at the centre of an international web of illegal and criminal conduct. In parallel, several policymakers in advanced countries are emphasising the need for enforcing the blacklisting tool against the territories that breach transparency standards. But does blacklisting work?

Banking secrecy is an evergreen issue in the national and international arenas. In the aftermath of the Global Crisis the fight against banking secrecy, as well as against banking secrecy havens, has become a priority in advanced countries. It is also a convenient way for political leaders of advanced economies to divert public attention away from other, domestic regulatory failures (Persaud 2009).

It is often the case that international organisations, as well as national governments, do not have strong legal instruments to impose strict measures to prevent and combat banking secrecy. For this reason, soft law practices such as blacklisting have been introduced. The aim of the soft law tools is to put the investigated country under intense international financial pressure, using the ‘name and shame’ approach. Under this approach, institutional regulatory organisations and/or national governments disclose the names of non-compliant countries and/or banks to the public, supplementing the disclosure with forms of official opprobrium. This approach is increasingly applied in the international context to address policy coordination problems among national policymakers and regulators.

The name and shame approach has been applied to increase worldwide country compliance with the international standards of the policy known as ‘anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT). In order to prevent and combat illegal financial flows, international organisations do not have hard legal instruments at their disposal. Therefore, they resort to blacklisting as a soft law practice.

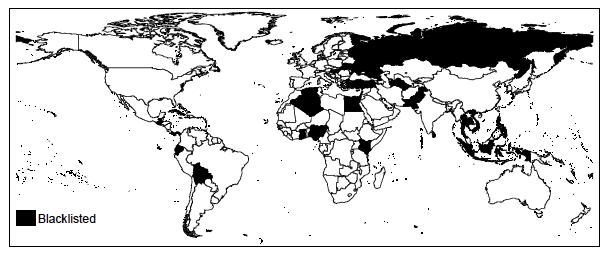

Established by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) in 1999, today the international standard consists of 49 Recommendations, dealing with anti-money laundering (40 recommendations) and combating terrorist financing (nine recommendations). Since 2000, the FATF has periodically issued lists (‘blacklists hereafter) of non-cooperative countries and territories, which identify the jurisdictions that the FATF believes to be non-compliant with international best practices. So far, 44 countries has been listed, including Panama (Figure 1); 12 of these countries and territories can be classified as part of the developed world.

The aim of a listing procedure is to put black-listed countries (BLCs) under intense international financial pressure, by employing the ‘name and shame’ approach in order to produce the so-called ‘stigma effect’ (Masciandaro, 2005a and 2008). By the stigma effect, we understand an inverse relationship between blacklisting and illegal international capital flows – the event of being blacklisted decreases the international capital flows to a country, and the opposite is true when a delisting occurs. Various sources of pressures on a BLC are expected to work.

First, most countries interacting with a BLC evaluate their financial transactions that are thought to be suspicious. This leads to more stringent and costly monitoring. Banks operating in multiple jurisdictions become more concerned by monetary costs, including compliance costs. The AML/CFT cost of compliance seems to continue to increase, at an average yearly rate of 45% (KPMG 2011).

Furthermore, financial transactions with a BLC can imply reputational costs. Suspicious financial transactions are attracting more and more attention from supranational organisations, national policymakers and regulators, and the international media. For a banking institution, engagement in opaque financial transactions can increase reputational risks. Just to cite the more recent and meaningful episodes, in 2012-15 various international banks were investigated for alleged illicit financial transactions and/or fined, and/or solicited to improve compliance (Powell 2013). Transactions with BLCs can produce similar negative reputational effects.

But both the existence and the direction of the stigma effect are far from obvious. As it was pointed out in different studies (Masciandaro 2005a, 2008, Masciandaro et al. 2007), the non-compliance of a country can be attractive under specific conditions, such as the potential existence of worldwide demand for non-transparent financial transactions. A BLC can be attractive for banking and non-banking institutions seeking to promote lightly regulated products and services to their wealthy and/or sophisticated clients. The international banking industry can have incentives to take advantage from the existence of BLCs.

Therefore the stigma effect, meant to be a ‘stick, can turn into a ‘carrot’. The ‘stigma paradox’ can thus emerge, as a specific case of regulatory arbitrage that creates the ‘race to the bottom’ strategy, which implies the desire to elude more prudent regulation (Barth et al. 2006). This strategy can noticeably influence international capital flows (Houston 2011).

The economics of the stigma effect have been analysed in depth by Picard and Pieretti (2011), who focused on the incentives that banks located in a BLC have for complying with the regulation. The blacklisting practice is interpreted as a policy for international pressure on the BLC bank, and the stigma effect holds when the pressure policy is strong enough. The possibility of the stigma paradox has been empirically demonstrated by Rose and Spiegel (2006). Using bilateral and multilateral data from over 200 countries in a gravity framework, they analyse the determinants of international capital flows, finding that for a country the status of tax haven and/or money launderer assigned by the international organisations can produce beneficial effects. The analysis confirmed that the desire to circumvent national laws and regulations can be a driver in shifting financial assets abroad.

New evidence

In a more recent study, my co-authors and I evaluate empirically the trend, magnitude, and robustness of the stigma effect, analysing the relationship between international capital movements and FATF listing/delisting events in 126 countries in the years from 1996 to 2014 (Balakina et al. 2016).

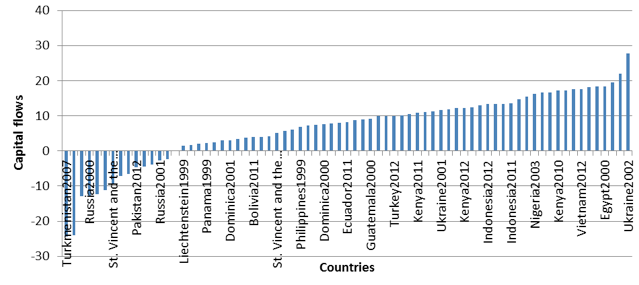

The variable of interest is a dummy variable, which is equal to 1 if the country is listed in the FATF list and 0 if the country complies with FATF conditions. The international capital flow measures are the growth rates of total inflows and outflows obtained from the BIS database. The stigma effect holds if a listing event is negatively associated with the capital flows; the visual description of the capital flows of the listed countries during the listing period (Figure 2) casts doubts on the robustness of the stigma effect. The econometric analysis confirmed that, in general, the stigma effect does not exist.

Therefore, is the era of banking secrecy definitively over, as a G20 official document stated in 2009? Probably not. The economic rationale of our results is easy to find out. If it is assumed that banking secrecy is the result of market mechanisms, it is natural to forecast that the worldwide demand for and supply of banking secrecy are likely to be relevant for a long time to come, and consequently the existence of tax and financial heavens.

Bottom line result

The growth of criminal and illegal activities systematically generates the demand for banking secrecy, while economic and political incentives can motivate national politicians and international banks to demand and supply banking secrecy. The use of a soft law practice such as blacklisting is likely to be a weak policy solution for a structural problem that has deep roots in the incentive structures of both offshore and onshore countries.

Banking secrecy is unlikely to disappear. It is a dynamic variable with booms and busts motivated by the changing preferences of national policymakers. Banking secrecy is a like a tango – it takes two to dance it. And the blacklisting is unlikely to stop the music.

About the author:

*Donato Masciandaro, Professor of Economics, and Chair in Economics of Financial Regulation, Bocconi University

References:

Balakina O, A. D’Andrea and D. Masciandaro (2016), “Bank Secrecy in Offshore Centres and Capital Flows: Does Blacklisting Matter?”, Baffi Carefin Working Paper Series, n.20.

Barth J.R., J. Caprio and R. Levine (2006), Rethinking Bank Regulation: Till Angels Govern, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Houston J.F., C. Lin and Y. Ma (2011), “Regulatory Arbitrage and International Bank Flows”, Journal of Finance.

KPMG (2011), Global Anti-Money Laundering Survey.

Masciandaro, D. (2005), “False and Reluctant Friends? National Money Laundering Regulation, International Compliance and Non-Cooperative Countries”, European Journal of Law and Economics, 2005, n.20, 17-30.

Masciandaro, D. (2008), “Offshore Financial Centres: the Political Economy of Regulation”, European Journal of Law and Economics 26, 307-340.

Masciandaro, D., E. Takats and B. Unger (2007), Black Finance. The Economics of Money Laundering, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham.

Persaud, A. D. (2009), “An Economic Defence of Offshore Financial Centres – Or How to Lose Your Liberal Friends in 800 Words”, VoxEU.org.

Picard, P.M and P. Pieretti (2011), “Bank Secrecy, Illicit Money and Offshore Financial Centres”, Journal of Public Economics 95 (7-8), 942-955.

Powell, J.H. (2013), Anti-Money Laundering and the Banking Secrecy Act, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, U.S. Senate, Washington D.C., March 7, mimeo.

Rose, A.K. and M. Spiegel (2006), “Offshore Financial Centers: Parasites or Symbionts?”, Economic Journal 117(523), 1310-1335.