A New Central Asia? Kazakhstan’s Drift From Moscow – Analysis

By Julian McBride

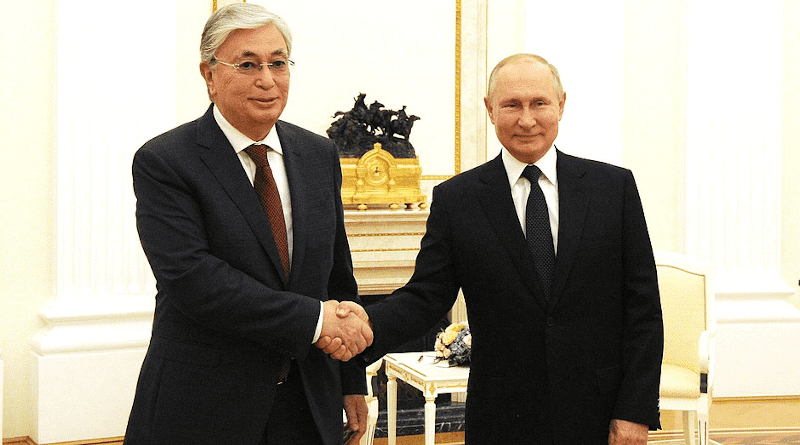

As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine escalates into brutal street-to-street combat in the Donbas region, the Kremlin has looked to gain international recognition for their proxy states before full annexation ala Crimea. Most international governing bodies have rejected any sort of recognition for the “LPR” and “DPR” save for states with longstanding despots such as Belarus, Venezuela, Eritrea, and Syria. What the Kremlin did not plan on, however, was a sharp turn from Kazakhstan’s President Tokayev who has refused to recognize Putin’s requests of backing illegitimate states in the Luhansk and Donetsk. This has followed months of belligerent talk from Russian MPs and talk show hosts of “disloyalty” from former USSR states, and it illustrates Russia’s weakening hold on Central Asia.

Russia has dominated Kazakhstan and most of Central Asia since the imperial conquests of Nicholas I. To consolidate those conquests, Russia sent Russian colonizers to change the demographics of the region, resulting in hundreds of thousands of Turkic people being forcibly deported to other regions. During the Soviet era, Kazakhstan was used as a point of deportation for Crimean Tatars, Pontian Greeks, Georgians, and others during Stalin’s brutal reign of terror. During the dissolution of the USSR, Kazakhstan was so committed to the union that it was the last state to secede; even the Russian Federation became independent before it. Moreover, earlier this year, the president of Kazakhstan had to request Russian and overall CTSO military assistance to help with a crackdown on protestors who were dissatisfied with Tokayev’s leadership, inflation, and corruption.

Yet despite this history of Russification and Russian political influence, Tokayev has also manifested a split with Moscow’s policies following the invasion of Ukraine.

The rift did not emerge for the first time last weekend. The Kazakh government, despite being protected by the Kremlin, turned down Putin’s request to send troops to Ukraine in late February. The rejection wasn’t particularly grating for Moscow at the time, which knew it still had a launch-pad in Belarus and assumed the war would end quickly, with few casualties. Fast-forward four months into the war and the quagmire in Ukraine has become protracted, with the Russian military suffering tens of thousands of casualties. The Kremlin has attempted to replace vast combat losses quietly and quickly without full mobilization of the public.

In May, there were rumors of Kazakhstan leaving the Eurasian Economic Union, the alternative regional bloc that Moscow drew up in opposition to the European Union. Kazakhstan denied the allegations, but the fear of losing vassals, such as Ukraine, has already been sowed in Russia. Astana also cancelled the annual Victory Day Parade of former Soviet states, reflecting the growing cultural separation from their former overlords. During this year’s Saint Petersburg International Economic Forum, Vladimir Putin publicly spurned Kazakhstan, stating it was “historically Russia.” In return, Tokayev stated he would abide by international law and not recognize the quasi-states Russia seeks to create in Ukraine to delegitimize Ukrainian sovereignty. However, Tokayev also stated he would not recognize Taiwan, effectively showing how Central Asia has leaned more toward Beijing as Russia’s grip on the region fades.

China has stepped up its own influence in the region with the expansion of the Belt and Road Initiative, along with the acquisition of key institutions under companies controlled the Communist Party. Turkey as well has attempted to subvert Russian authority in Central Asia in order to promote pan-Turanism. As Russia’s military continues to be depleted in the Ukraine war, you can expect both China and Turkey to step up influence in the region despite cooperation with Russia from both states.

Kazakhstan has not been the only country under Russia’s cooperative umbrella that has signaled a wind of change. On April 28th, Kyrgyzstan, a fellow Eurasian Economic Union and CTSO member rejected a Russian request to build a “biosafety” lab. The actual content of the lab was vaguely discussed, but the episode reflected the Kremlin’s waning influence over Kyrgyzstan’s sovereignty, along with some double standards as Moscow has spread its own bioweapon conspiracy with regard to the U.S. China also shares a border with Kyrgyzstan, which has a minority Chinese population. Beijing and Ankara have also looked to expand there as Moscow’s power fades.

Predictably, Russian media pundits and personalities have been outspoken over “disloyalty” from countries who do not follow the Kremlin’s narrative within Russia’s sphere of influence. Recent comments from Russian media commentators such as Tigran Keosayan and Margarita Simonyan have threatened Kazakhstan, with the former warning that the Kazakh government should “look at Ukraine carefully, think seriously.”

There may be some truth to the warning, as history has shown that Russia has not been kind to say the least toward former Soviet states seeking to split from Moscow, such as the Baltics, Georgia, and Ukraine.

Kazakhstan is home to a large Russian minority, which could be used as a casus belli for intervention if the country were to decisively split from Moscow, much like the Kremlin did with Ukraine and Georgia, and what it threatens to do with Moldova. Kazakhstan, with its subpar military and little in the way of geographic advantage, thus has to be careful its its foreign policy toward Russian. However, even despite these concerns, Kazakhstan has recently shown the world that Russia’s hegemony in the region is now fading even faster amid the Ukraine war. Time will tell if Kazakhstan looks to become fully independent of Moscow or looks to China as a new emerging power.

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com