Considerations On Legal Approach To Dispute Settlement: The Philippine Experience With South China Sea Arbitration – Analysis

By FSI

By Edcel John A. Ibarra*

The filing of a case against China was a historic moment in Philippine foreign relations: it was the first time that the Philippines resorted to the international judiciary to settle a political dispute.1 In retrospect, the effort was well worth it, at least from a legal standpoint. On 12 July 2016, three years since filing the case on 22 January 2013, the Philippines secured a favorable ruling which clarified important aspects of the South China Sea disputes. However, the new Philippine administration decided to set aside the Award. Critics blamed President Rodrigo Duterte for not taking advantage of the ruling, but they failed to see the limitations inherent in the legal approach itself. The legal approach denotes the referral of disputes to an international court or tribunal for a binding decision in accordance with international law (Keohane, Moravcsik, and Slaughter 2000, 457). Should the Philippines consider using it again to settle a dispute, foreign policy makers must understand its viability and limitations.

The South China Sea arbitration case can offer some valuable insights on the complexities of the legal approach to dispute settlement. Five considerations on the legal approach can be gathered from the Philippine experience.

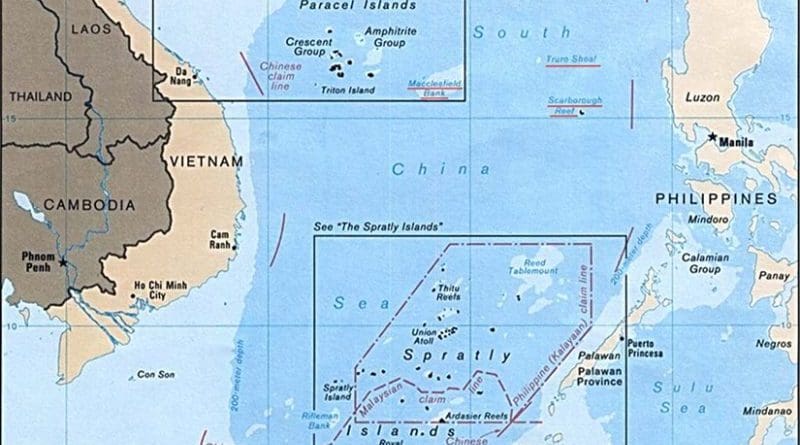

First, the legal approach is only feasible if the claim has a firm legal basis and if the case can be submitted to a forum having jurisdiction. The Philippines filed the case on the South China Sea believing that its claim would hold up well in a court of law, especially against China’s position. The Philippines’ submissions were strongly grounded in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), unlike China’s “nine-dash line” claim, which, at the outset, exceeded the 200-nautical-mile–limit set by the Convention, relied on “historic rights” existing outside the Convention, and infringed on the rights of coastal states given by the Convention. Indeed, the Philippines’ claims were later upheld by the Arbitral Tribunal.

An international court or tribunal, however, can only settle legal disputes over which it has jurisdiction. This depends on whether both disputants have previously consented, expressly or implicitly, to the court or tribunal’s authority to deliver a binding ruling on the issue. State parties to UNCLOS, including China and the Philippines, consented to UNCLOS dispute settlement mechanisms when they ratified the Convention, but this consent does not normally extend to sovereignty disputes. China additionally withheld its consent on compulsory dispute settlement relating to maritime boundary delimitation, historic bays and titles, military activities, and fisheries law enforcement, among others, in 2006. The Philippines thus had to avoid in its submissions questions of sovereignty (who owns the features?) as well as issues falling under the exceptions declared by China. Instead, it had to deal exclusively with questions of maritime entitlement (what rights over the surrounding waters do the features generate?). This careful framing of the dispute allowed the Arbitral Tribunal to exercise jurisdiction and decide the case.

States can refer disputes to two types of adjudicative forums: a permanent court or an arbitral tribunal. A permanent court is established indefinitely to resolve all cases that may be given to it, while an arbitral tribunal is formed only to settle the specific case lodged to it. The selection of judges, scope of applicable law, and procedure are usually already predetermined in a permanent court, but these may be flexibly specified by the disputants in forming an arbitral tribunal. Permanent courts, however, are less costly (being paid by the international community) and are generally deemed more prestigious (having judges presumed to have developed professionalism throughout their tenures), which makes their rulings potentially more authoritative (Bilder 2007, 198–205). Thus, the choice of forum can be strategic.

UNCLOS provided for a choice among two permanent courts (the International Court of Justice [ICJ] and the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea [ITLOS]) and two arbitral tribunals (one constituted under Annex VII and a special arbitral tribunal constituted in accordance with Annex VIII). Unfortunately, neither China nor the Philippines had previously declared consent to the ICJ or ITLOS, but the Philippines had the option to negotiate a special agreement with China jointly granting jurisdiction to either permanent court. However, knowing that China at that time would not agree to such an arrangement, and knowing that arbitration under Annex VII of UNCLOS allows for proceedings to continue even if China would refuse to participate, the Philippines strategically chose an arbitral tribunal rather than insist on a permanent court.

Second, the legal approach is not exclusive from other approaches to the peaceful settlement of disputes and can, in fact, go together with them. In the UN Charter, the legal approach—which includes arbitration (adjudication through an arbitral tribunal) and judicial settlement (adjudication through a permanent court)—is only one method of resolving disputes. Other methods include negotiation, enquiry, mediation, conciliation, and resort to regional or international agencies. Indeed, the Philippines at that time pursued the legal approach (arbitration) simultaneously with two other approaches: a “political” approach (multilateral engagement of ASEAN) and a “diplomatic” approach (continued bilateral discussions with China on other issues).

Third, even though the legal approach is peaceful and depends on mutual consent by the parties, it can be viewed by the defendant state as unfriendly and adversarial, thus potentially damaging the bilateral relationship. Such was China’s reaction to the arbitration case. It returned the Philippines’ notification and statement of claims, refused to formally participate in the proceedings, and publicly denounced the ruling. Moreover, despite the Philippines’ efforts to engage its neighbor on other areas, China set restrictions on the import of agricultural products from the Philippines and issued an advisory against traveling to the country. It also repeatedly accused the Philippines of escalating tensions in the region. If states are thus to insist on the legal approach, they must also explore simultaneously pursuing conflict prevention and management strategies.

Fourth, the legal approach ultimately relies on the parties to enforce the settlement by themselves; it does not end with securing a favorable ruling. China’s rejection of the ruling is telling because there is no higher authority that can compel states to comply with international rulings. Absent the willingness of one party, the other party will have to induce compliance through other means. The Philippines initially attempted to rally international support to raise the reputational cost of noncompliance for China, but under President Duterte, it decided to set aside the ruling in favor of improving bilateral ties, hoping that it will eventually shape a regional environment more conducive for compliance. Other states may face the same problem with the legal approach because even if a party agrees to refer the disputes to an international court or tribunal, the agreement is not an assurance that that party will eventually comply with the ruling.

Finally, the legal approach cannot guarantee dispute resolution. Despite the Philippines’ efforts, the South China Sea disputes remain unresolved and incidents are still being reported. For one, the arbitration only settled questions of maritime entitlement and left open questions of sovereignty, which lie at the core of the disputes. For another, China rejects the ruling, which, if respected, can prevent incidents at sea, reduce tensions, and breed mutual trust and confidence among the claimant states. By itself, the Arbitration Award is an important step toward eventual dispute settlement in the South China Sea, but political realities must always be considered with the legal approach. However comprehensive the ruling may be in clarifying the issues, disputes will continue absent the political will and commitment of all parties to reach a settlement.

With these considerations, it is clear, drawing just from the Philippine experience, that the legal approach is inherently limited and its viability depends on many other factors. The legal approach is, at the core, a means to an end. It is not enough to develop solid, shatterproof legal arguments, but states must also be careful about whether to throw them at all and, if one decides to go with the legal offensive, be skillful about how best to deploy them. The choice of forum, the deployment of simultaneous conflict prevention and management approaches, and the post-verdict strategy to ensure compliance are as important as, if not more important to, having well founded legal claims. Ultimately, the success of the legal approach depends not only on legal brilliance but also on political and diplomatic ingenuity. The Philippines succeeded in securing a legal victory that changed the geography of the South China Sea disputes to its advantage. China’s “nine-dash line” claim was shown to have no legal basis; the extent of the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone was clarified and its rights therein were affirmed; and the legal status of the disputed features were established. The challenge now is to induce China’s compliance and translate the legal victory into concrete gains.

About the author:

*Edcel John A. Ibarra is a Foreign Affairs Research Specialist with the Center for International Relations and Strategic Studies of the Foreign Service Institute. Mr. Ibarra can be reached at [email protected]. The views expressed in this publication are of the authors alone and do not reflect the official position of the Foreign Service Institute, the Department of Foreign Affairs and the Government of the Philippines.

Source:

This article was published by FSI. CIRSS Commentaries is a regular short publication of the Center for International Relations and Strategic Studies (CIRSS) of the Foreign Service Institute (FSI) focusing on the latest regional and global developments and issues.

Endnote

- The Philippines had sued other countries to resolve international economic disputes under the World Trade Organization Dispute Settlement Mechanism. The Philippines had also submitted an application before to the International Court of Justice to intervene in a sovereignty case between Indonesia and Malaysia over the Ligitan and Sipadan Islands, but the Court eventually rejected it.

References

Keohane, Robert O., Andrew Moravcsik, and Anne-Marie Slaughter. 2000. “Legalized Dispute Resolution: Interstate and Transnational.” International Organization 54, no. 3 (Summer): 457–488. https://www.princeton.edu/slaughtr/Articles/IOdispute.pdf.

Bilder, Richard. 2007. “Adjudication: International Arbitral Tribunals and Courts.” In Peacemaking in International Conflict: Methods and Techniques, edited by I. William Zartman, rev. ed., 195–226. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1641165.