The Coming Global Coronavirus Contraction – Analysis

Despite China’s success in containment, the novel coronavirus is exploding in the US and Europe. The contraction will shake economies, politics and governments worldwide.

As the accumulated confirmed cases of the novel coronavirus (Covid-19) continue to soar, there is no immediate deceleration in sight. The official figures are just the tip of the iceberg. In the US and Europe, mobilization is 1-2 months late.

In China, the impact of the coronavirus is easing, but imported cases have only begun. Outside China, epidemiologists currently anticipate a peak around June. If that’s the case, economic damage in China would be largely limited to the first quarter, but international economic damage would endure into the second quarter, and in the most affected countries well beyond.

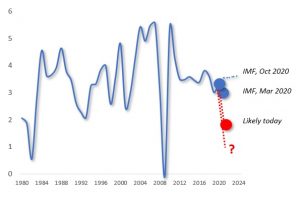

In early March, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projected global growth to fall 0.1 percentage points from the expected 3.3%. The estimate was too optimistic. In view of current data, a global contraction could cause economic growth prospects to plunge closer to 2% and below. The explosive growth of virus cases in the US and Europe will compound those rates in the rest of the world – which, in turn, could further undermine the year-end outlook (Figure).

Depending on the outcome of the virus battle in Europe and particularly the U.S., one plausible but dark scenario is that the battle against the coronavirus may last through the ongoing year and possibly through 2021.

China toward rebound

Thanks to China’s draconian measures, reported cases peaked and plateaued between January 23 and 27, and have largely declined since then.

Before the crisis, Chinese economy was benefiting from a mild recovery. In early March, IMF projected China’s growth to fall to 5.6% in 2020. Now estimates in the West anticipate baseline growth of less than 5%, with significant downside risk of less than 3%. In January, factory activity did contract at the fastest pace on record, as did the services activity. Yet, both plunges were only to be expected.

Economic shocks translate to contractions. The real question involves the strength of the post-shock rebound between mid-March and April, given the low starting-point.

As the populous country is moving from containment to the mitigation stage, the challenge will be to contain new imported cases in the borders, while quickly extinguishing potential new virus clusters at home. That will be the key challenge in Asian countries that are likely to prove relatively successful in containment.

In economic terms, China and the rest of Asia must prepare for the negative feedback effect from the world economy. In North America and Europe, the plunges of the 1st quarter are only a prelude to the carnage in the 2nd quarter.

Contraction in US…

Despite elevated warnings since mid-January, uncertainty began to grip the rest of the world only at the end of February. Instead of mobilizing against the virus, complacency in advanced economies led to a series of missteps, including faulty and belated local testing, failures in evacuations and quarantines, lax enforcement of self-quarantines. Hence the consequent multi-trillion-dollar market corrections.

Worse, thanks to a misguided and ill-timed price war, oil prices have plunged a whopping 60% since January 1, down to $20 per barrel. As the virus impact has not yet been fully factored into the prices, crude oil could fall even further.

Recently, the IMF projected US growth to suffer a slowdown from 2.0% to 1.6%. But the estimate is too optimistic. If the second quarter carnage proves limited, U.S. growth could still stay close to 0.2%-5%. But the risks are on the downside and, after a series of policy mistakes, the margin of error is slim.

After the White House’s delays in the outbreak management, the Fed cut interest rates close to zero, starting $700 billion quantitative easing, while pushing for liquidity. That is likely to be coupled with a $1.3 trillion fiscal stimulus. In the short-term, these moves are understandable. In the long-term, they will compound new risks. Under Trump, U.S. sovereign debt has soared faster than in decades – and now it will accelerate even more.

Despite their indebted economies, central banks in Europe, the UK and Japan will follow US footprints into more monetary and fiscal accommodation. In 2008-9, that worked. But if infection rates continue to soar, even these measures will not pacify virus fears, anxious markets and uncertain economies.

… Eurozone

Before the virus, the Eurozone quarterly growth was 0.1%; the weakest in seven years. Now things will get a lot worse. German GDP will stall further, France and Italy will remain in contraction. In the UK, annualized growth is likely to fall fast from 1% to contraction territory.

Soaring infection rates have already reversed Spain’s growth pickup. With sovereign debt at 134% of its economy, Italy is struggling against infections and deaths that are climbing faster than in any other major economy.

If the virus cases continue to soar in the Eurozone, regional growth prospects are likely reverse fully into contraction territory. In the most affected countries, the failure of timely containment is likely to foster a recession through the first half of the year.

If the virus cases continue to climb in the second quarter, the contraction will prove steeper. A potential protracted appreciation of the euro – a déjà vu of the sovereign debt crisis in the early 2010s – could penalize growth even into 2021.

If the virus is not managed appropriately, the consequent hit will cast a shadow over the hoped-for rebound in the second half of 2020 and beyond.

… And Japan

Prior to the coronavirus, Japanese growth contracted 0.7% in the fourth quarter of 2019, thanks to last fall’s consumption tax. With or without the Olympics, the outcome will further weaken the world’s most rapidly aging major economy that’s been in secular stagnation since the mid-90s.

In 2019, South Korea’s economy grew 2%, the slowest in a decade. With some 9,000 confirmed cases, expansion is reversing, and growth is plunging. Additionally, Australia and the regional financial hubs Singapore and Hong Kong are on their way to or in contraction. Since these countries are significant investors in Southeast Asia, their challenges will reverberate across emerging Asia.

Amid the struggle to restore their pre-virus output level, emerging economies will face an economic tsunami from the West. That will cause huge pressures on weaker healthcare systems and cast a dark economic shadow over countries depending on capital inflows and commodity reliance (Indonesia, Mexico and South Africa) or excessive debt (Turkey).

What is urgently needed is multipolar cooperation among major economies and across political differences. Otherwise, worse nightmare scenarios will loom ahead.

This is a short version of Dr Steinbock’s COVID-19 briefing on March 16, released as “The Global Coronavirus Contraction” by the World Financial Review (March/April) on March 23, 2020