Reflecting On Pesach (Passover) – Analysis

Pesach is a very important holiday in the Jewish religion. It celebrates the exodus of the Jews from Egypt and the birth of Israel as a people. It also inaugurates the beginning of the barley harvest season. (1)

Considered as the Jewish Passover, Pesach begins at nightfall on the 14th of Nissan (in March or April depending on the year) and lasts for 8 days. Its celebration includes the Feast of Unleavened Bread, and is characterized by the prohibition for believers to eat food containing leavened flour.

The History of Pesach

The festival of Pesach commemorates the liberation of the Hebrews from slavery in ancient Egypt. By performing the rites of Pesach, they relive and feel the real freedom achieved by their ancestors.

After many decades of slavery under the Pharaohs of Egypt, during which the Israelites were forced to do overwhelming labor, God saw the plight of the people and sent Moses to Pharaoh with this message: “Let My people go, that they may serve Me. “

When Pharaoh refused to obey the command, God sent ten devastating plagues upon Egypt, destroying the livestock and the people. In the middle of the night of the 15th of Nissan in the year 2448 from creation (1313 B.C.), God inflicted upon the Egyptians the last of the ten plagues, killing all of their first-born. In doing so, God spared the Children of Israel, “leaping over” their homes – hence the name of the holiday: Pesach means “leaping” in Hebrew. (2)

Pharaoh literally drove his former slaves out of the land, and the Israelites left in such a hurry that the bread they were to use for the road did not have time to rise.

600,000 adult men, and many more women and children, left Egypt that day, beginning their journey to Mount Sinai and their birth as God’s chosen people.

In ancient times, the observance of Pesach included the sacrifice of the Passover lamb, which was roasted and eaten at the Seder on the first night of the holiday. This was the case until the Temple in Jerusalem was destroyed in the first century. (3)

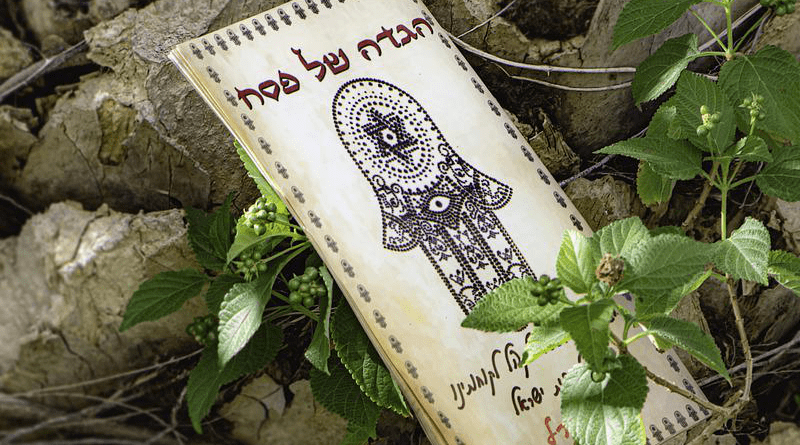

It is this story that is traditionnally read, in Hebrew, in the text on Pesach night, (4) in a book called the “Haggadah”. (5)

The wanderings in the desert

If the Hebrews are chosen by God to seal his covenant with mankind, they are first of all a “stiff-necked” people [Book of Exodus]. And this character is far from being a quality, so much so that their resistance to the divine orders will delay them, according to tradition, in the great plan that he has conceived for them.

Nevertheless, in the obstinacy of doing as they please lies certainly all the depth of the peregrination of the Hebrew people recounted in the Books of Exodus and Numbers: the Hebrews are above all human, and it is with this humanity that they will follow Moses into the desert – a geographical place which, in a spiritual reading, must be understood in a symbolic way.

“The wanderings in the desert are the image of the inner life of the believer” and its trials are “so many purifications of the human heart“, explains the religious writer Philippe Plet in his book: Les Hébreux au désert. Lecture du Livre de l’Exode (6) (a spiritual reading of the biblical episode). Walking in the desert requires an initial act of faith: the Hebrews advance towards a land only promised as the believer walks in himself armed with the only certainty that he is going towards God. (7)

But before reaching the land “flowing with milk and honey” (“So I have come down to deliver them out of the hand of the Egyptians, and to bring them up from that land to a good and large land, to a land flowing with milk and honey, to the place of the Canaanites and the Hittites and the Amorites and the Perizzites and the Hivites and the Jebusites.” (Exodus 3:8)), (8) they must endure the desert, first of all a place of light and deprivation, and therefore of purification. It is also a place of temptation – Jesus will spend forty days resisting the devil – because everything is missing.

And it is precisely because everything is lacking that, laid bare, man cannot take refuge behind the vanities of worldly life. The violence of the trial can therefore shake the believer, as it inspires the murmurs of the Jewish people against their fate.

Two months after leaving Egypt, the Hebrews are thirsty and hungry. They rage: “Why did we not die at the hand of the Lord in Egypt, when we sat by the meat pans, when we ate bread to our fill? Instead, you led us into this desert to starve this whole assembly” (Exodus 16:3). (9) Faced with the difficulty of the path of faith, the believer is tempted to turn back and return to Egypt.

Here, the land of Pharaoh is the metaphor of a world of immanence, from which the spiritual journey must lead one to emerge. With its monuments, its paintings and its statues, “Egypt is by nature the world of images” and appearances, analyzes Philippe Plet, who sees a parallel with the current world. According to him, “to leave Egypt was therefore to leave the world of images and idols, to enter the desert without form, which purifies the sight of all human representations [and] prepares for the contemplation of God. “

Pesach, the festival of freedom

After 400 years of enslavement in Egypt, the Jewish people led by Moses are finally liberated. According to the Old Testament, ten plagues were necessary to convince the Pharaoh to let the Jews go, (10) among which the death of all the first-born in Egypt. The word “Pesach”, which means “to pass over” in Hebrew, refers to this plague, since the death spared the Jewish houses and fell only on the firstborn Egyptians.

For eight days, Jews do not eat any food containing leaven, hence the consumption of unleavened bread cakes called matzot, in memory of the flight of the Hebrews, who, in their haste, carried the bread away before it was leavened. The leavened food, called Hametz, (11) must be removed from the house, resulting in a great cleaning for this celebration. (12)

At the Seder meal, different foods are presented, each with a strong symbolic meaning. The Passover lamb is a reminder of the night of the Exodus when the Hebrews sacrificed a lamb as a sign of their conquest of freedom. The lamb, in fact, was considered by the Egyptians as a sacred animal, a god. (13) Sacrificing a lamb was therefore their first act of freedom. Herodotus, in his survey of Egyptian customs, writes (Histories, 2:42): (14) “Now all who have a temple set up to the Theban Zeus (=Amun) or who are of the district of Thebes, these, I say, all sacrifice goats and abstain from sheep… the Egyptians make the image of Zeus (=Amun) into the face of a ram… the Thebans then do not sacrifice rams but hold them sacred for this reason.’’

Bitter herbs are also found on the table, as a reminder of the bitterness of slavery. The Seder ceremony is marked by a reminder of the story of the exit from Egypt, where the children are invited to ask their questions.

There are similarities between the Christian feast of Easter and the Jewish feast of Passover. The Passover lamb is common to both feasts, but there is also a connection between the unleavened bread and the bread Jesus consecrated at the Last Supper. In fact, the Christian holiday of Passover bears this name because, according to the Gospels, the death and resurrection of Jesus took place during the period of celebration of Pesach. (15)

Meaning of the term “Pesach”

The term Pesach means “to leap, to pass over” in memory of the ten plagues, and in particular that of the death of the first born, from which the Hebrews were spared. It is said that death passed “over” (16) their houses which were distinguished by a red mark on their lintels (made with lamb’s blood): “I will recognize this blood and I will pass over you; the plague will not take hold of you“. (17) By extension, it is to be protected from any misfortune that Jewish houses carry a mezuzah (a box containing two biblical passages written on a small parchment) to the right of their entrance doors.

This holiday is also called:

– “Feast of Unleavened Bread” (Hag Ha matsot)

– The Festival of our Freedom” or “The Time of our Freedom” (Zman Khirotenu, Hag Hakhirut)

– The Festival of the Sprouting of the Barley/Springtime (Hag Ha Aviv).

Particularly rich in rites and customs, the festival was originally distinguished by the Passover offering (lamb) which the Jews have not been able to perform since the destruction of the Temple (the Samaritans continue to offer it on Mount Gerizim). But also the great cleaning of ” Pessah ” (or of Spring) where the leaven (hametz) must be eliminated from the home. This is any food or product that comes from or derives from the fermentation of the five cereal species (wheat, barley, rye, oats, spelt) by the addition of ferments, heating or contact with moisture or water and having risen for more than 18 minutes.

This cleaning generally begins after the holiday of Purim (one month before), (18) which does not prevent a meticulous search for hametz on the eve of the holiday, (19) that is to say on the evening of the 13th of Nissan (this craze will be explained in Hasidic literature by the desire to drive out the “spiritual hametz“, i.e. the “evil inclination”, through the material).

The hametz must then be searched for throughout the house by candlelight, beginning at nightfall before the holiday. (20) Whatever is found during this search must be burned in the morning of Pesach Eve. Kitchen utensils must also be removed by boiling or heating them to a white heat; since not all utensils can be subjected to such processes, it is customary to have a set of dishes reserved for the week of Pesach. (21) Alternatively, some people sell their hametz to a non-Jew, possibly planning to buy them back after the holiday week.

According to rabbinic law, the practices of Pesach include: (22)

– The prohibition of consuming, possessing, profiting from or seeing hametz;

– The obligation to eat matzot (unleavened bread made of water and wheat flour, without yeast and made in less than 18 minutes) and maror (bitter herbs symbolizing the hard life lived by the Hebrews in slavery in Egypt);

– The Seder (23) (festive meal with an order of prayers to be respected) with the reading of the Haggadah (book telling the life of the Hebrews at the time of Pharaoh and the exit from Egypt), answering the four questions asked by the youngest children (in the form of a song: “My nichtana“?) and containing the story of the 10 plagues that afflicted the Egyptians; (24)

-The four cups of wine, symbolizing the festive meal and freedom from slavery, the tray made of harosset (paste of dates, nuts and grape juice) remindful of the mortar that the Hebrews, slaves of Pharaoh, used to make, bitter herbs (maror), a bone (zroha) symbolizing the strong arm with which God brought the Hebrews out of slavery in Egypt and an egg symbolizing the unity of the Jewish people.

Pesach means “passage”:

- Passage of the angel of death over the houses of the children of Israel (thus passage from death to life);

- Passage from slavery to freedom;

- Passage through the Red Sea;

- Passage from the non-existence of Israel to its constitution as a people, and;

- Passage from winter to spring.

The celebration of Pesach

Pesach (25) is divided into two parts:

(a) The first two days and the last two days (which commemorate the opening of the Red Sea) are days of full celebration. The festive candles are lit at night, and the Kidush is made followed by a festive meal on both nights and days. One does not go to work and refrains from driving, writing or turning on and off electrical appliances. Cooking and carrying outside is permitted.

b) The middle four days are called ‘Hol Hamoed, the half holidays, “intermediate days”. Most work is permitted during these days.

To recall the unleavened bread that the Israelites consumed upon leaving Egypt, Jews must refrain from eating or even possessing any form of “hamzah” from mid-day on the eve of Pesach until the end of the holiday.

Hametz is grain that has risen. It is therefore any food or drink containing even a trace of wheat, barley, rye, oats, spelt or their derivatives that has not been supervised to prevent fermentation. This includes bread, cakes, cookies, cereals, pasta and most alcoholic beverages. In addition, most manufactured food products are presumed to be hametz unless verified and certified otherwise. (26)

Clearing of homes of hametz is a meticulous job. It involves a thorough spring cleaning in the weeks leading up to Pesach and culminates in the ceremony of searching for hametz the night before Pesach. The next morning, the found hametz are burned to remove them completely. Hametz that cannot be disposed of may be sold to a non-Jew for the duration of the holiday. (27)

The holiday begins with a seder (traditional meal) and continues for seven days during which no hametz (leavened or fermented food) is eaten.

The Seder Tray (ke’ara) is a special utensil containing six dishes – symbolic elements for the Passover Seder. Each of the six elements placed in the Seder tray has special meanings in the story of the Exodus from Egypt. They are: Z’roa, Beitzah, Maror, Harosset, Karpass, Hazeret. (28) On this Seder table are represented all the symbols of Pesach to evoke its first moments dictated by God. It is the first Passover celebrated in Egypt.

The Pesach table has one seat not yet occupied, that of the prophet Elijah. (29) To allow him to enter, the door is left open and a cup of wine is poured for him.

On this particular point Rabbi Or Rose writes: (30)

‘’The notion that Elijah will return at the end of days to usher in the Messianic age is based on the dramatic description of his departure from the earth in II Kings. While the Bible tells us that great figures like Abraham and Moses died, Elijah ascended to the heavens on a “fiery chariot” in a “whirlwind” (II Kings 2:11). This tradition also led to the development of a genre of folktales about Elijah’s role as an intercessory figure, who would appear—often incognito—to help those in need.

Elijah’s name is also invoked at various Jewish ritual moments, including intergenerational and other liminal times. Doing so brings us solace, strength, and hope as we move, often haltingly, between life experiences. At the seder we welcome Elijah towards the end of the evening, as we turn our attention from the original redemption of our ancestors from Egypt to the future redemption. ‘’

The philosophy of Pesach

Tolerance is the essence of the Jewish Passover. The word “Pesach” means the mouth that tells. The ritual is based on a series of questions and answers, for the primary quality of man is to have the ability to question. Jews, therefore, celebrate the liberation of speech, the very foundation of tolerance and coexistence. (31)

However, the word “tolerance” can have a negative connotation. “Tolerating someone implies that the other feels superior“. “One has to go further. One must aim at recognition, at total respect for the other“. The term “tolerance” should be understood as the right to be different while respecting the life of the other.

According to the Torah, each human being is created in the image of God and for this reason each one is worthy. (32) This is the basis of Jewish philosophy. One must help the other person out of the conditions that deny his or her dignity.

Pesach conveys five concepts that have become true sacred formulas for living a productive and successful life. (33) These are five essential concepts to know about the holiday and to integrate into one’s daily lives. Because they have animated the soul of the Jewish people for thousands of years, these concepts have earned them the privilege of fulfilling, to a large extent, the prophetic role entrusted to them: “To be a light among the nations“. (34)

Here are, then, five words that describe the most beautiful contributions Jews have made to humanity: remembrance, optimism, faith, family and responsibility towards others.

1. The importance of memory

Upset by the way the Jewish people have literally transformed the world, an incredible answer is evident in many Torah texts. Because they were slaves in Egypt, then they must empathize with the oppressed of every generation. Because they were slaves in Egypt, they must be concerned about the rights of foreigners, the homeless and the poor. Because they have known oppression, then they, more than any other nation, must understand the pain of the oppressed.

Their tragic encounter with Egyptian injustice was meant, in large measure, to prepare them to serve as spokespersons for future generations, so that they can identify with anyone who is suffering. Undoubtedly, the concept of history is one of the most important Jewish inventions. “Remember that you were a stranger in the land of Egypt,” and “Remember that God brought you out of slavery.” Memory is a biblical injunction that apparently interested no other people than the Jews. And it is the story of Pesach that is the source of this duty to remember.

2. The importance of optimism

The story of Pesach makes one realize that the most difficult task that Moses had to face was not to get the Jews out of Egypt, but to get Egypt out of the Jews. They were so used to living as slaves that they had lost all hope of changing their fate.

The real miracle of Pesach – and its impact across generations – is the powerful message that with God’s help, no difficulty is insurmountable. A tyrant like Pharaoh can be dethroned. A nation as powerful as Egypt can be defeated. Slaves can become free men. The oppressed can break the chains of captivity. Everything is possible, if one only dares to dream the impossible.

3. The importance of faith

It is said that the pessimist is the one who does not believe in an “invisible help”.

The Jewish optimist, on the other hand, firmly believes in a help that comes “from above”, from a caring God. It is this faith in a benevolent God that gives one confidence in oneself, in one’s future and in one’s ability to change the world.

The God of Sinai did not say “I am the Lord your God who created heaven and earth” but “I am the Lord your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage.” In theory, the God of Creation could have forsaken this world once his task was done. But the God of the Exodus made it clear that He is constantly involved in the history of Jews and that He is committed to their survival.

4. The importance of the family

Pesach teaches another great truth: perfecting the world begins at home, with one’s own family.

God built his nation not by commanding hundreds of thousands of people to gather in a public square, but by asking Jews to turn their homes into a place of family worship, and to do so around a seder whose central activity is to answer the children’s questions.

This is the obvious! Children are the future. They are the ones who need attention the most. And the home is the first place where they form their identity and values.

5. The importance of responsibility towards others

An important question must be asked as one celebrates one’s divine deliverance from Egyptian bondage. One must thank God for delivering him, but why did God allow Jews to become victims of such mistreatment?

An incredible answer is evident in many Torah texts. Because Jews were slaves in Egypt, then they must empathize with the oppressed of every generation. Because they were slaves in Egypt, they must be concerned about the rights of foreigners, the homeless and the poor. Because they have known oppression, then, they, more than any other nation, must understand the pain of the oppressed.

The Jews tragic encounter with Egyptian injustice was meant, in large measure, to prepare them to serve as spokespersons for future generations, so that they can identify with anyone who is suffering.

Final word

The holiday of Pesach, which celebrates greatest series of miracles, is a time to rise above nature to reach the miraculous dimension of existence. But how are miracles accomplished? Take matzah for example: flat and tasteless, it embodies humility. By ridding oneself of oversized egos, one becomes able to tap into the miraculous source of divine energy that all humans have in their souls.

The current world is shaken by frequent crises: they are social, economic, climatic and now sanitary. Or perhaps it is the same crisis that is expressed in different forms? One is shaken, one suffers, one is in danger. What solutions can one bring to this? Nobody knows. Probably nobody has a ready-made solution. But one can do as the Sages in the Haggadah did: open one’s mouth, talk about it, think together, build the chains of thought that will deliver humanity from the present chains which are binding it. Like the Sages in Bnei Braq, humans must have the spark of genius that will bring them true freedom, the freedom that increases their joy of living and the hope for a better future for humanity.

You can follow Professor Mohamed Chtatou on Twitter: @Ayurinu

End notes:

- Hayoun, Maurice-Ruben. La Haggadah de Pessah : La Pâque juive. Paris : Presses Universitaires de France – PUF-, 2011.

- Alcoloumbre, Thierry. « Israël comme peuple : entre Juda Hallévi et Maïmonide », Pardès, vol. 45, no. 1, 2009, pp. 189-201.

- Ritmeyer, Leen. The Quest: Revealing the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Jerusalem: Carta, 2006.

- The Pesach Haggadah (Hebrew: הַגָּדָה שֶׁל פֶּסַח “Passover narrative,” also known among Yemeni Jews as Babylonian Judeo-Aramaic: אגדתא דפסחא) is a ceremonial ritual for the Jewish Passover Seder, which derives its name from the main element, the narration of the exodus from Egypt prescribed in Exodus 13:8.

- Yerushalmi, Yosef Hayim. Haggadah and History. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1974.

- Plet, Philippe. Les Hébreux au désert : Lecture du livre de l’Exode. Paris: Salvator Editions, 2018.

- https://www.jewishhistory.org/the-wilderness-years/

- https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Exodus%203%3A8&version=NKJV

- https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Exodus%2016%3A3&version=NIV

- Greifenhagen, F.V. “Plagues of Egypt”, in Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Amesterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2000, p. 1062.

- The Bible prohibits the eating of leaven during the festival of Passover (Exodus 12:15-20). The Hebrew word “hametz” is translated as leavened bread and refers to food prepared from five species of grain–wheat, barley, oats, spelt, and rye–that has been allowed to leaven. To these, Ashkenazic authorities add rice, millet, corn, and legumes, collectively known as kitniyot. [It should be noted that the Conservative movement has declared that kitniyot may be consumed on Passover even by its Ashkenazic followers.]

- The rule against leaven applies not only to its consumption but also to enjoying any benefit thereof and even to its possession. Therefore, before the arrival of Passover, all leaven must be removed from one’s premises. Nor should one have leaven in his legal possession.

- Assmann, J. Farber, Z. ‘’Sacrificing a Lamb in Egypt”, TheTorah.com, 2016. https://thetorah.com/article/sacrificing-a-lamb-in-egypt

- Lloyd, Alan B. “Herodotus’ Account of Pharaonic History.” Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte, vol. 37, no. 1, 1988, pp. 22–53, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4436037

- Daise, Michael A. “‘Christ Our Passover’ (1 Corinthians 5:6–8): The Death of Jesus and the Quartodeciman Pascha.” Neotestamentica, vol. 50, no. 2, 2016, pp. 507–26, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26417647

- McGinnis, Claire Mathews. “The Hardening of Pharaoh’s Heart in Christian and Jewish Interpretation.” Journal of Theological Interpretation, vol. 6, no. 1, 2012, pp. 43–64, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26421434

- https://www.history.com/topics/holidays/passover

- Purim is a Jewish holiday of biblical origin and rabbinic institution, which commemorates the events recounted in the Book of Esther: the miraculous deliverance from a large-scale massacre planned against them by Haman the Agaggite in the Persian Empire during the reign of Ahasuerus (Xerxes I).The festival is celebrated every year on the 14th of Adar (in February or March of the Gregorian calendar). When the month of Adar is doubled (embolismic years), Purim is celebrated on 14 Adar II. This date corresponds to the last Full Moon of winter, one moon before the first Full Moon of spring, marked by the festival of Pesach. To the traditional practices, recorded in the Book of Esther and ordered by the Sages of the Mishna, were added various customs, notably culinary, with the hamantaschen or deblas (ears of Aman), as well as joyous and carnivalesque demonstrations, and the use of rattles at the evocation of the name of Haman. Cf. Elliott Horowitz. Reckless rites: Purim and the legacy of Jewish violence. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2006.

- Bedikat Hametz: Searching for Leaven. The night before Passover, immediately after sundown, one begins the search for leaven (Code of Jewish Law, Orach Chayyim 431:1). The aim of the search is to be sure that no leaven has been left behind after the cleaning of the house. The procedure includes these items: a candle; a feather, which acts as a broom; and a wooden spoon into which the pieces of bread will be scooped.

- Kitov, Elyahu. The Book of Our Heritage. The Jewish Year and its Day of Significance Vol. I Translated by N. Bulman Tishrey –Shevat. New York & Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers, 1973, p. 518.

- Upbin, DAnielle. “Searching for Chametz in Home and Heart: Shloshim for Ari Gold Z”L, 5781” , Sefaria, https://www.sefaria.org/sheets/307890?lang=bi

- Klein,Isaac. ‘’The Laws of Passover’’, JTS, February 11, 2013. https://www.jtsa.edu/torah/the-laws-of-passover/

- The seder (Hebrew: סדר “order”) is a highly symbolic Jewish ritual specific to the festival of Pesach, aimed at making its participants, especially the children, relive the sudden accession to freedom after the years of slavery in Egypt of the children of Israel.

- Sicker, Martin. A Passover Seder Companion and Analytic Introduction to the Haggadah. Bloomington, Indiana: iUniverse, 2004.

- Bokser, Baruch M. “Unleavened Bread and Passover, Feasts of”, in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman (New York: Doubleday), 1992, 6:755–765.

- https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/why-do-some-jews-burn-hametz/

- https://www.sefaria.org/sheets/157761?lang=bi

- https://www.chabad.org/holidays/passover/pesach_cdo/aid/1998/jewish/The-Seder-Plate.htm

- Rose, Rabbi Or. ‘’Elijah the Prophet and the Passover Seder: Intergenerational Questions and Connections’’, Hebrew College, April 14, 2O2O. https://hebrewcollege.edu/blog/elijah-the-prophet-the-passover-seder-intergenerational-questions-connections/

- Ibid

- Goltzberg, Stefan. “Three Moments in Jewish Philosophy”, Bulletin du Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem, 22, 2011, http://journals.openedition.org/bcrfj/6615

- Altmann, Alexander. “‘Homo Imago Dei’ in Jewish and Christian Theology.” The Journal of Religion, vol. 48, no. 3, 1968, pp. 235–59, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1202149

- Cahill, Thomas. The Gifts of the Jews: How a Tribe of Desert Nomads Changed the Way Everyone Thinks and Feels (The Hinges of History). New York: Anchor Books/Nan A Talese, 1999.

- Hugenholtz, Rabbi Esther. “’A Light unto the Nations’ Proposals of Missionary Judaism”, Academia.edu, 2013. https://www.academia.edu/36141574/A_Light_unto_the_Nations_Proposals_of_Missionary_Judaism

- Dimbert, Seth. ‘’The Sages in Benei Brak (The Jonathan Sacks Haggadah, 107-117)”, Sefaria. https://www.sefaria.org/sheets/104631?lang=bi