NATO In The South Caucasus: Present For Duty Or Missing In Action? – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Col. Robert E. Hamilton*

(FPRI) — The recent NATO Heads of State and Government Meeting in Brussels highlighted NATO’s declining relevance in the South Caucasus and the declining relevance of the region to NATO. The reasons for this lie both within NATO and within the South Caucasus. In NATO, the focus on the Russian threat to the Alliance’s eastern flank, the debate over burden-sharing, uncertainty over the U.S. commitment to Article 5, and members’ concerns over terrorism leave little room for NATO to think seriously about its role in the South Caucasus. This change in relevance was evident in Brussels, where NATO leaders agreed the Alliance would sustain its mission in Afghanistan, join the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS, and continue its mission to train Iraqi security forces. They also agreed that each Alliance member would develop an annual plan setting out how it intends to meet its commitment to spend 2% of GDP on defense, with 20% of that budget invested in equipment. Finally, they agreed that NATO would maintain its dual-track approach toward Russia, combining deterrence with dialogue. Absent was any meaningful discussion of NATO’s role in the South Caucasus.

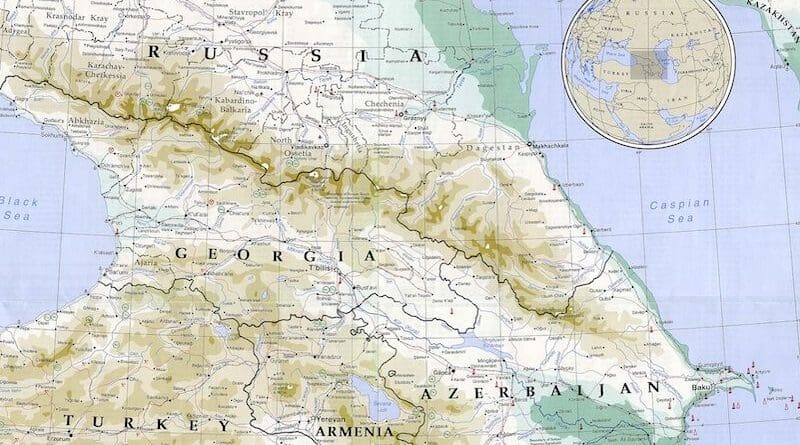

For its part, the South Caucasus presents an unfortunate combination of fractionalization and susceptibility to Russian pressure, which helps explain NATO’s recalcitrance toward the region. Unlike the Baltics, where a high level of unity and cooperation among the three regional states helped them resist Russian pressure and enter NATO together; and the Balkans, where despite the geopolitical fractures in the region, its distance from Russia tempers Moscow’s ability to apply direct military pressure to those states wishing to join NATO; the South Caucasus possesses both of these disadvantages in abundance. Armenia and Azerbaijan remain in conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh, making regional cooperation impossible, and Russia retains leverage over all three regional states. For Armenia, Russia is its only true ally; for Azerbaijan, Russia retains the ability to play the spoiler to its hopes of regaining control over Nagorno-Karabakh; and for Georgia, Russia presents a clear military threat. All of these factors have combined to prevent NATO cooperation with South Caucasus countries.

How to Engage a Fractured Region?

The lack of unity and cooperation in the South Caucasus extends to the attitudes of regional states toward NATO. Whereas Georgia’s entire foreign and security policy is oriented on Euro-Atlantic integration, with NATO membership as the natural culmination of this policy, neither Armenia nor Azerbaijan is interested in joining the alliance. The fractionalization of the region presents NATO with the problem of how to engage a region with little regional identity or cooperation.

One method might be to use engagement and assistance as inducements for regional countries to increase cooperation. But this method has little chance of working in the South Caucasus, as the divisions between Armenia and Azerbaijan—still technically at war over the breakaway Azerbaijani province of Nagorno-Karabakh—are too deep to be bridged by any inducement NATO could provide. Another possibility would be to disengage from the region until it stabilizes, presumably under the weight of Russia’s geopolitical presence. But given the proximity of the South Caucasus to Europe, its role as an energy corridor and commercial bridge between Europe and Asia, and the potential for conflict within the region to destabilize the broader Black Sea region, which includes several NATO members, the alliance had historically deemed the South Caucasus too important to ignore. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, then, the South Caucasus had presented NATO with a dilemma. On one hand, the region’s fractionalization made engagement on the regional level impossible, while on the other hand, NATO had important interests in the region.

NATO’s answer to this dilemma had been to focus its engagement on Georgia, while maintaining communication Armenia and Azerbaijan. The Alliance’s engagement of Georgia, led by the U.S., paid off in the form of deployments of Georgian troops to NATO missions in Kosovo and Afghanistan, and to the U.S.-led coalition in Iraq. Georgia’s deployments were significant for both the numbers of troops deployed and the missions they undertook. In Iraq, the Georgian contingent eventually numbered some 2,000 soldiers, and was tasked with patrolling and interdicting the insurgent supply routes running from the Iranian border to Baghdad. In Afghanistan, the Georgian contingent numbered some 1,600 soldiers at the height of its strength, and was deployed to volatile Helmand Province. Some 800 Georgian soldiers remain in Afghanistan today. In all, over 8,000 Georgian soldiers have deployed to Iraq, and over 13,000 have deployed to Afghanistan so far. The Georgian contingents in Iraq and Afghanistan were the largest non-NATO contingents and dwarfed those of most NATO members.

Aside from its military deployments, Georgia’s desire for Euro-Atlantic integration was a key factor in the impressive political and economic reforms the country has undertaken over the last fifteen years. Georgia transitioned from a failing state with a kleptocratic government to a messy but vibrant parliamentary democracy that has conducted one of the few peaceful constitutional changes of power in the former Soviet Union, outside of the Baltics. It also includes an economic transformation and fight against corruption that moved Georgia from near the bottom of global indices of economic freedom and transparency to near the top.

But NATO’s current preoccupation with other issues threatens to undo much of what went right with its past policy toward the South Caucasus. One of these issues is the strained relationship between the United States and many European alliance members. Fabrice Pouthier and Alexander Vershbow called for a “concrete renewal of vows between the United States and Europe” at the 25-26 May NATO Heads of State and Government Meeting, warning that if doubts about the U.S. commitment to NATO persisted, the U.S. might “assume a posture of transactional unilateralism” and Europe might turn inward. Unfortunately no such renewal of vows occurred. While NATO joined the coalition against ISIS and member states agreed to take concrete steps toward meeting their defense spending commitments, reciprocal U.S. steps were not forthcoming. Indeed, President Trump’s failure to explicitly affirm his support for NATO Article 5 at the meeting will increase uncertainty about the U.S. commitment to the Alliance, despite the attempts of several of his advisors to assure members that it remains ironclad. Pouthier and Vershbow’s warning seemed dismally prophetic when, shortly after the meeting, German Chancellor Angela Merkel remarked that Europe could no longer “rely fully on others.”

Where NATO Can—and Should—Help

None of the above bodes well for a sustained NATO role in the South Caucasus. An alliance uncertain about the commitment of its most important member, straining to meet its commitments to Afghanistan, and faced with a renewed Russian threat to its eastern flank is unlikely to be able to think strategically about a region its members currently see as important but not vital to their security. But inattention to the South Caucasus could have serious long-term negative effects, and a continuing—and even expanded—NATO role in the region would not be difficult to realize. The following three steps could help to stabilize the region and protect NATO’s interests there at little cost to alliance members.

First, NATO should continue its policy of prioritizing relations with Georgia while keeping channels open to Armenia and Azerbaijan. Georgia’s path toward Euro-Atlantic integration has not been risk-free or cost-free. Many of the reforms its governments have undertaken involved painful adjustments that, while they will pay off over the long-term, involved short-term costs that the Georgian people were asked to bear. Georgians were and remain willing to tolerate these costs at least partly because they see them as requirements for integration into the Euro-Atlantic community.

Aside from the economic and social costs involved in pursuing a Euro-Atlantic course, Georgia also incurred military costs. By keeping large numbers of its military deployed to U.S. and NATO-led military operations while facing a clear Russian military threat, Georgia incurred significant risk to its security. This risk was made manifest in August 2008, when Russia and Georgia went to war over the separatist Georgian regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, and some 20% of the Georgian Army was unavailable to defend the country because it was deployed to Iraq.

NATO made clear in the final communique from its April 2008 Summit that Georgia and Ukraine would become members of the Alliance. Both Georgia and Ukraine subsequently suffered Russian military interventions that left significant portions of their territory under Russian military occupation. NATO’s failure to move forward on the pledge to accept Georgia and Ukraine into the Alliance, especially when combined with statements from the U.S. administration that leave the U.S. commitment to Article 5 in question, erode NATO’s credibility as a collective security organization and contribute to instability and insecurity along NATO’s eastern flank. NATO should continue to reaffirm the 2008 commitment at every major meeting, and should publish a clear list of tasks Georgia needs to accomplish to gain Alliance membership.

The next step NATO should take is to include the South Caucasus into its campaign against ISIS. As the only region in the world that shares borders with NATO, Russia, and the Middle East, the South Caucasus is uniquely positioned to play a role in NATO’s campaign against the terrorist group. Integrating the region into its campaign would improve regional stability and enhance NATO’s credibility in several ways. Because Russia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan all have citizens that have left the Caucasus to fight for ISIS in Syria and Iraq, and all share a concern about the return of these fighters to their home countries, NATO assistance in this area would help to stabilize the region and provide a rare opportunity for these three states to cooperate. Because the defeat of ISIS is the current security priority of the United States, American support for this initiative should not be difficult to gain. NATO assistance in this area could focus in the areas of intelligence-sharing and border security, neither of which are overly expensive or complex undertakings.

Finally, NATO should create a separate Special Representative for the South Caucasus. The current Special Representative handles both the South Caucasus and Central Asia, despite the fact that the two regions matter to NATO in very different ways. The South Caucasus borders a NATO member (Turkey) and contains a country designated as a future member (Georgia). While the Central Asian States are important to NATO’s assistance mission in Afghanistan, they are geographically far from NATO and none of them are candidates for membership. Naming a Special Representative for the South Caucasus would send a signal that NATO is serious about its role in the region.

None of these steps would be significantly costly for NATO to accomplish but, taken together, they would signal a renewed NATO interest in the security and stability of the South Caucasus and lend renewed legitimacy to NATO’s Open Door policy. Failing to invigorate its presence in the South Caucasus and to take concrete steps to reaffirm the Open Door policy could significantly damage NATO’s credibility. As Tracy German noted in a recent article on the issue, “If NATO ultimately rejects any prospect of membership for states in the post-Soviet space, they could be abandoned to Russian influence, indicating that Moscow has a de facto veto over membership of the alliance and conceding spheres of influence to Russia.” This outcome would undermine NATO’s entire purpose as a political and military alliance dedicated to democratic values and the peaceful resolution of disputes, but possessed of the military power and the will to collectively defend its members if required.

The views expressed are the author’s own and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Army War College, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

About the author:

*U.S. Army Colonel Robert E. Hamilton is a Black Sea Fellow at FPRI.

Source:

This article was published by FPRI