Shadow Governance: Right To Vote And Rule In Azad Jammu & Kashmir – Analysis

By Javaid Hayat

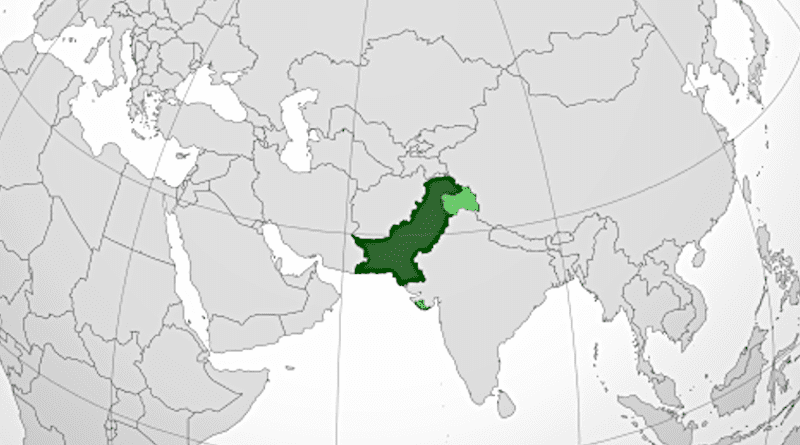

The controlled ‘democratic’ mechanisms in different divided region of former princely state of Jammu & Kashmir doesn’t fulfill needs and aspiration of the peoples rather than these are maintenance of status quo as per need of national and security interests of respective controlling countries namely India and Pakistan.

The politics and power distribution in Pakistan-Administered Kashmir (PaK) commonly known as ‘Azad Jammu & Kashmir’ (AJK) is conditioned by three main factors. Firstly, it is driven by the Kashmir conflict at large, which resulted in AJK acquiring a disputed status that further lead to interim arrangements and uncertainty. Secondly, becoming a de facto federal unit of the state of Pakistan, it has been sidelined from the mainstream which – in turn – created ‘systematic’ dependency in almost all spheres of political, economic and societal life of AJK. Thirdly, at the internal level, ethnicity or cross-cutting cleavages based on tribes (biradri) and a regional divide (based on Districts and Divisions within Azad Kashmir) plays a significant part in political shaping and reshaping. Traditional politicians also encourage such divide for their own vested interests, thus, racial identities appear to be an increasingly growing phenomenon for internal power-sharing and political allegiances in future.

The provisional setup formed on October the 24th 1947 came into existence by virtue of a freedom movement that was arguably only partially indigenous. The title ‘Azad State of Jammu & Kashmir’ was initially declared by emphasizing that the (Dogra) State of Jammu & Kashmir was a single entity. However, neither India and Pakistan, nor the international community ever recognized this government as a sovereign state. Therefore, the official nomenclature ‘Azad Government of the State of Jammu & Kashmir’ remains a paradox in the study of international relations.

The search for autonomy or self-rule as compared to regional or provincial equality in terms of rights and obligations is an unfolding debate in AJK, especially after the 18th constitutional amendment in Pakistan where greater provincial autonomy was given to the provinces. Many politicians and writers often argue that AJK has its own self-governance structure and some even do not hesitate in describing it as an autonomous territory. That may be theoretically correct but empirically it appears not, as much of the literature on governance concerns the way power is exerted and shared, and more pointedly, in the manner through which resources are allocated within a society.

In this respect, two major schools of thought on power-sharing were identified which reflect the parameters of the debate: consociational and the integrationist approach. Renowned intellectual Stefan Wolff describes, “one of the key questions to ask any self-governance regime is where powers rests; i.e. how different competences are allocated to different layers of authority and whether they are their exclusive domain or have to be shared between different layers of authority”. In the context of AJK’s Interim Act 1974 – which many now explicitly consider as a document of slavery – ostensibly a self-governance structure exists, however (and crucially) effective power rests with the Government of Pakistan through its Kashmir Council, which in turn is being operated by its Ministry of Kashmir Affairs and Northern Areas (KANA).

An analytical study of the Interim (Constitutional) Act of 1974 indicates many weaknesses, which seem systematically enshrined, thus causing fragility in governance on one hand and allowing the (Kashmir) Council to function as a parallel government on the other. Headed by the Prime Minister of Pakistan as chairman alongside five other non-state (subject) residents, holds exclusive authority over 52 subjects of governance under the aforementioned Act. This leaves behind minimal executive power to the AJK Government, thus limited to running the day to day affairs of this territory. The Kashmir Council that emerged from the Interim Act not only holds exclusive rights of tax and revenue collection from AJK and income from the Maharaja’s assets in Pakistan but it also holds responsibility (and power) of inspection and monitoring through the Accountant General’s offices throughout all districts of AJK. Moreover, the AJK Assembly or the government has no authority to make the Council accountable before any judiciary or accountability bureau in AJK. Interestingly, it is akin to giving responsibility of protecting assets to a thief by making him the gatekeeper, a well-known journalist from AJK added. Therefore, how can a government be considered as functioning as a self-government which does not even have permission to collect taxes from its territory and willingly pass on the welfare of its people. According to Tanveer Ahmed – a civil society activist – AJK is a legal anomaly and the current governance structure in AJK is most certainly not a structure, which accommodates accountability and transparency of any kind.

The history of AJK indicates that the right to vote and the existing basic governance structure wasn’t easily obtained, rather than political parties put up an incredible political struggle even for attaining these rights which form just a modicum of what was envisaged in the United Nations’ charter. However, what little was attained was subsequently further diluted, at the cost of strengthening self-government and promoting good governance in the region. Some analysts believe that the mere holding of elections is a sufficient condition for the existence of democracy. In this respect, the sole rationale given by the traditional political elite of AJK is that democracy has sustained by virtue of elections being held uninterrupted since 1985, thus providing testimony of continuity of ‘democracy’. That may be partially correct in the sense that elections are the paradigm of enforceable accountability. Indeed, there is no other form of participation and accountability as direct as ‘free and fair elections”. A pre-condition for democracy no doubt.

However – there is always a risk – proved by studying the history of politics, elections and government formation in AJK that certain groups or parties having more resources, strong ties and support from the ruling party in Pakistan, have always won these elections held in AJK. It also needs to be considered that some essential elements required for democratic governance are lacking in AJK’s current ‘democratic’ structure; including an independent judiciary, independent election commission, transparent and genuine electoral rolls. Additionally, it requires well-functioning political parties that represent ideologies/policies rather than tribes or regions and an accessible media that is free and impartial, not one controlled by the state or corporate sector. Further, it needs a vibrant civil society, which can play a watchdog function and provide an alternative form of political participation.

Therefore, democracy is more than just having the right to vote and only voting or elections shouldn’t be considered as democracy.

It is revealed in several recent studies that power-sharing and the dilemma of governance in areas of limited statehood has become extremely challenging. They indicate increasing political rifts, social deprivation and intensified conflict. In addition, complex or imbalanced power-sharing between a contested territory and its controlling nation-state appears to be a substantial obstacle in deepening participatory democracy or establishing a genuine autonomous governance structure.

Power-sharing involves a wide range of political and constitutional arrangements in which stakeholders (political, ethnic and pressure groups) are guaranteed influence and representation in governance. In the context of AJK, one can see ‘politics of accommodation’ is on the rise and the only beneficiaries are ‘elite cartels’, not ordinary citizens who remain at the mercy of elites or members of the ruling class. Critics argue that ordinary people are merely voters, who are allowed to cast their vote in a given controlled mechanism whereby ‘electoral engineering’ authorities sitting in Islamabad actually decide the outcome of elections in AJK. Besides this, the 12 refugee seats (out of 41 contested) based on voters living in Pakistan form a bargaining-chip to manipulate the political process before government formation in AJK. Consequently, in AJK where people have the right to vote but don’t have the right to rule exemplifies the characteristics and type of ‘democratic fabric’ this region entails. Understandably, in this globalized world and fast-changing environment, politics has to be more substantial than merely giving people the right to vote. It is about promoting democratic politics, which require public participation and accountability as two core attributes for democratic governance.

In this last decade, issues pertaining to the status of AJK, ownership of natural resources, and empowerment of the people in a truly democratic mechanism have been discussed among political parties, civil society and media. This has led to some academic intervention, conferences and panel group discussions in AJK. They found the structure unjust which left insufficient space for self-governance in this region. In addition, this has failed to address the national question including sovereign rights and fragility of governance. There is consensus amongst the political parties of AJK on redefining the current relationship with the government of Pakistan based on Act 1974. The only difference appears to be on strategy.

Against this backdrop, it is quite clear that political and constitutional reforms are required in AJK that include reforms in the election commission, judiciary, taxation, local bodies’ election and ownership of natural resources. There is a need to revisit Act 1974 together with the preceding Act of 1970, which provided a quantum of autonomy to AJK and frame a new constitution with the consultation of all stakeholders. However, there is a distinct difference of opinion on what exactly AJK should seek for. Some are in favour of restoring a sovereign government which takes some reference and spirit from the declaration of October the 24th 1947. Former Chief Justice of AJK High Court Majeed Malik, Tanveer Ahmed, Sardar Aftab Ahmad Khan (a UK-based political and social activist) and nationalist forces are in favour of such a solution. This remains an ideal scenario but perhaps not practicable in the given circumstances. Others are in favour of restoring Act 1970 with only one exception, that of converting it into a parliamentary form of government. Thirdly, some support the idea of giving AJK something close to a ‘provincial’ status but without declaring it a province. In this respect, the basic theme has been presented by retired jurist Manzoor Gillani. In a similar vein, an Australian analyst Christopher Snedden, in his recent book ‘The Untold Story of the People of Azad Kashmir’ argues that AJK’s de facto link should be made de jure with Pakistan.

It is necessary to accept and acknowledge – at first instance – the conflicting issues between Muzaffarabad and Islamabad. Shoving these issues under the carpet and adopting a carrot and stick approach, which has been a consistent strategy of Islamabad when dealing with AJK, needs to be changed. Therefore, a more inclusive and constructive approach requires both parties to address the genuine political and constitutional needs of AJK. In my opinion, a genuinely wide-reaching autonomy could provide the best answer to the current predicament of AJK until the final disposition of the Kashmir conflict. Peter Sellers once said, “What you need around here is a government that isn’t afraid of doing a little governing”.

This article was updated on August 11, 2012

A good article but written out of the historical realities my humble suggestion would be that the Kashmir issue needs to be linked to its origins that is the 15 August position 1947 and the Indepoendence Act of India 1947

On 15th Augst 47 the power to govern the state were tranferred to the people who should have make a decision of their furuture once the Amrfitsar agreement become null and void.

With this as the base line all measures taken by any force are unlawful and require endorsement my by the people of J&K through their elected representatives after the occupational forces are removed from the state.

Maharaja Hari Singh was in no position to make any agreement with any country after the said date and his agreement with India also does not carry any legal value.

Today a new social contract is required for the people of ther State and the rule to govern the state needs be transfferred back the representatives.

Again when you talk about the systeme in Pakistan Aministered Part of Kashmir all the acts are unlawful and the agreements like Act 1970 should be considered null and void till the free will of the people is determined and a representative government of the state enters into a new social contract with government of Pakistan.

Taking different territories separately is not going to break any ice rather it would be an attempt to put a final seal on the division of kadshmir without taking into consideration the free will of the people.

Dear Misfer hassan, Thanks for your insight. I do agree partially with many of your views. However, this piece is needs to be seen the context it is written. And aim wasnot to talk about legitimacy and where it lies from historical context rather to highlight that different divided regions, which runs under different governance structures are actually systems maintaing status quo and conditioned with their national and security interests not exaclty providing and meeting with the needs of local populations. I will take into account your arguments in some next publication. Thanks agian