How Death Of Mao Zedong Ushered In New Geopolitical Era

By SwissInfo

By Thomas Bürgisser, DODIS

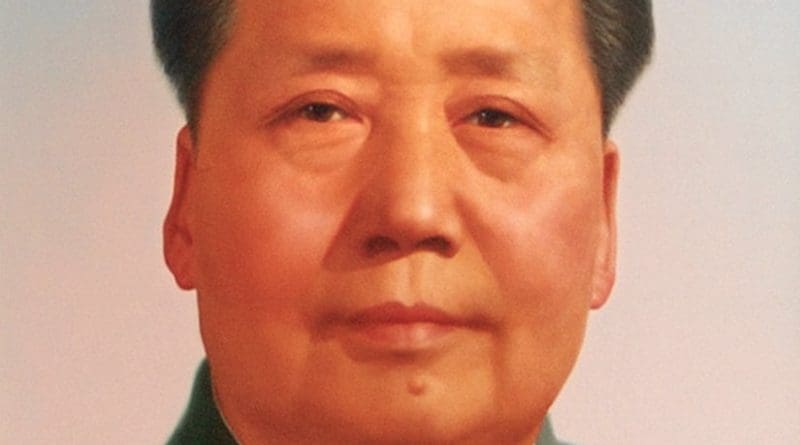

Mao Zedong, known as the “Great Helmsman” passed away on September 9, 1976. He laid embalmed in a glass coffin at the Great Hall of the People (China’s parliament) for a week. Over one million Chinese turned out to bid him farewell. The foreign diplomatic corps also paid its last respects. In his diary entry of September 14, Swiss Ambassador Heinz Langenbacher quoted his son, who was with him at the ceremony.

“A reclining Buddha, stoic beyond feeling and time, ancestor worship and a visit to the waxworks.” It had also reminded him of “Snow White in the glass coffin”.

Geopolitical turning point

The death of Mao heralded the start of the Chinese economic fairytale, which continues to this day. It put a definitive end to the Communist Party’s mass campaigns to destroy the previous social order, the process of forced agricultural collectivisation and industrialisation and the “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution”, which had claimed millions of lives. It also paved the way for a policy of economic reform and opening up.

In the immediate aftermath of Mao’s death, however, this development was far from certain. When Ambassador Langenbacher left Beijing in March 1977, much was still unclear. “There is no evidence to suggest that the intrigues and conspiracies that have characterised the turbulent history of the past decade shall now end,” the embassy said at the time in its notes published by Dodis, a research centre investigating the archives of the diplomatic documents.

Nevertheless, on leaving his post, Langenbacher emphasised that “after the dramatic events of 1976”, China’s future now seemed “brighter and clearer than ever” to him. “This optimism will also have an impact on bilateral relations and open up new opportunities,” he added, predicting the new scope for action that would result from the policy of openness under Deng Xiaoping’s leadership, which was consolidated in late 1978.

Half-mast

In the then rigidly anti-communist Switzerland, the death of the preeminent founding figure of the People’s Republic aroused mixed reactions. Revealingly, the government very nearly made a blunder with regard to flag protocol.

On September 14, 1976, the Swiss Foreign Minister, Pierre Graber, noticed with consternation that the Swiss flag over the Federal Palace in Bern was not set at half-mast, as is customary on the death of a foreign head of state. The Chief of Protocol had clearly not considered the death of Mao – who was not China’s incumbent president, but officially only the chairman of the Communist Party and of the Central Military Commission – as requiring an expression of the Swiss government’s condolences.

Graber took his officials firmly to task for this “too rigid interpretation of the protocol”. This lack of courtesy contrasted strongly, he felt, with the messages of sympathy from around the world, and could have serious political repercussions for Switzerland’s bilateral relations with Beijing.

Switzerland – a close ally of China?

Graber had already recognised, in a keynote address to the diplomatic corps in autumn 1971 – under the impression of Henry Kissinger’s visit to Beijing and US President Richard Nixon’s upcoming trip to China – that the centre of gravity of world politics was shifting from Europe to Asia. In future, he believed, China would again play a role in international politics “that corresponds to its geographic and demographic clout”.

After the upheavals of the Cultural Revolution, Swiss trade diplomats were looking forward to a normalisation of relations, and enthused about future market outlets in the “huge Chinese empire with its 800 million potential customers”.

In August 1974, Graber himself travelled to China – the first Swiss cabinet minister ever to do so – for the opening of the Swiss Industrial Technology Exhibition in Beijing. By December of that year, a trade agreement had been signed between the Swiss Confederation and the People’s Republic.

During his short period of service in Beijing, however, Heinz Langenbacher remained sceptical of China’s eulogies to Swiss neutrality and defensive capacity, its stated pleasure at Switzerland’s early recognition of the People’s Republic in 1950, and its extolling of supposedly common mentality traits shared with its “old friend”. All this was, in his view, mere “window-dressing”.

He was convinced that the Chinese communists still saw Switzerland as part and parcel of the inexorably doomed capitalist world. Apart from economic utilitarianism, the hope of skimming off technological know-how and interest in international Geneva as a hub, Switzerland was “of no great relevance to China”.

In the diplomat’s view, the political leaders in Beijing had alarming gaps in their knowledge of the West. The Chinese, with their “often thinly disguised, centuries-old feeling of superiority”, often simply didn’t care about other countries.

As Swiss-Chinese contacts multiplied with the economic opening of the People’s Republic after Mao’s death, the number of players seeking to reach mutual agreements also increased. Thus, in 1980, the Swiss lift manufacturer Schindler became the first foreign business to enter into a joint venture with a Chinese company.

*Thomas Bürgisser is a historian at the Swiss Diplomatic Documents Research Centre. The documents quoted can be found here. https://dodis.ch/C2116