Ertuğrul: A Turkish Delight For Pakistan – Analysis

By Institute of South Asian Studies

The Turkish drama series, Diriliş: Ertuğrul, has taken the Muslim world by storm. Ever since Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan came to power in 2002, there has been a conscious effort to not just go back to Islamic roots, but also rehabilitate the Ottoman Empire. The show has been a great success in Pakistan too, fortifying its relations with Turkey and promoting Islamic values as envisaged in Prime Minister Imran Khan’s “Medina” dream.

By Nithya Subramanian*

Diriliş: Ertuğrul (Resurrection: Ertuğrul), a Turkish drama series set in the 13th century, has captured the hearts of billions of viewers across 72 countries. Loosely based on the life of Ertuğrul Ghazi, the father of Sultan Osman, who founded the Ottoman Empire, the television show has become Turkey’s most famous exports.

Produced by the country’s national broadcaster, Turkish Radio Television (TRT), the main protagonist, Ertuğrul, is the son of the Kayi tribe leader, Suleyman-Shah. He is portrayed as a brave warrior who gallantly fights the Crusaders, Templers, Byzantines and Mongols, while also professing his undying love for the Seljuk Princess Halime Hatun.

The five-season show has all the elements of popular entertainment – romance, elaborate action sequences, grand music and opulent costumes – which led to the moniker Muslim Game of Thrones. However, what has set it apart from the other Turkish drama is the depiction of Islamic values, often including words of wisdom from Ibn ‘Arabî of Andalucía – one of the greatest Muslim philosophers, thereby appealing to the Muslim diaspora across the world.

TRT said that the show has the “ability to connect global audiences through shared values.” 1 Released in 2014, this series has captured audiences in not just the Muslim world, but also in Latin America and Africa. A sub-titled version was released on Netflix in 2017, while it has been dubbed in six other languages and broadcast in 72 countries.

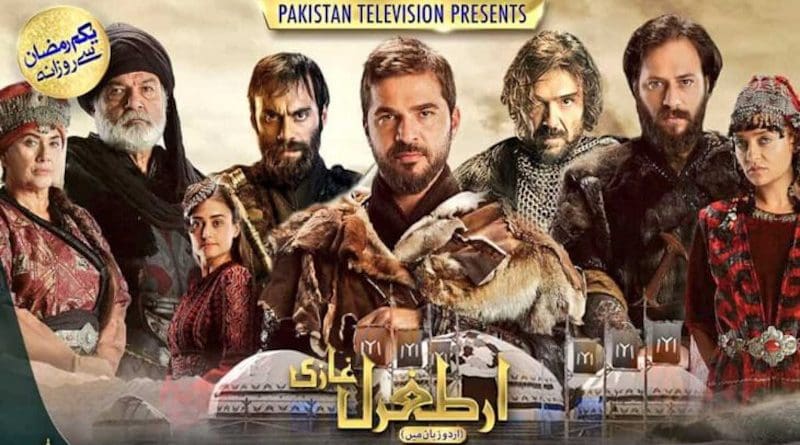

Turkey’s President, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has been a great proponent of this drama series as it is in line with the Justice and Development Party’s (AK Party) efforts to promote Islamic values and the Ottoman glory. Another country where Ertuğrul has gained huge popularity is Pakistan. Prime Minister Imran Khan first recommended the series to the people of his country in 2019. In April 2020, as part of Ramazan special, the show was dubbed in Urdu and aired by the national broadcaster Pakistan Television on its official YouTube channel.

Pakistan makes up 25 per cent of Ertuğrul’s global audience on YouTube. By November 2020, it had garnered over 9.62 million subscribers, while the episodes collectively have over 1.7 billion views. The series has also been a big hit on Netflix in Pakistan, being consistently ranked among the three most-watched shows in the country since January 2020.

Promoting Islamic values has been high on the agenda of both Turkey and Pakistan in recent years. In September 2019, on the sidelines of the United Nations (UN) General Assembly, in a trilateral meeting with Erdoğan and then Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, Khan had proposed the setting up a dedicated television channel to promote Islamic values and counter Islamophobia. He had tweeted: “Misperceptions which bring people together against Muslims should be corrected; issues of blasphemy should be properly contextualised; films would be produced about Muslim history to educate our own people and the world; Muslims should be given a dedicated media presence.”

Though bilateral relations between Turkey and Pakistan have been mainly focused on political, military and economic engagement, there seems to be a deepening of cultural connections. While Ertuğrul is not the first series to gain popularity in the country — Muhtesem Yuzyil (‘Magnificent Century’, known in Pakistan as Mera Sultan) and Ask-i Memnu (‘Forbidden Love’, known in Pakistan as Ishq-e-Mamnoon) were also both huge hits – its popularity is unsurpassed.2

Turkey’s Renewed Quest for Ottoman Glory

Television is the most popular form of entertainment in Turkey. Known as dizi, these sweeping historical epics cover a wide range of subjects propagating Islamic values, also reflecting the mood of the nation. The growing interest in its television shows around the world, which is a good indication of the country’s rising soft power, is evident in its television export revenues. Worldwide, it has become the second largest exporter of television content after the United States (US). According to estimates, Turkish series exports, which stood at about US$150 million (S$202 million) in 2013, rose to approximately US$350 million (S$472 million) in 2017 and $500 million (S$674 million) in 2018.

The themes of these drama series have evolved over the years. While TRT had started producing historical dramas in the 1980s, this was also a period of soap operas and telenovellas. This was followed by the arrival of private broadcasters in the early 1990s, but since the middle of the decade, rising Islamism affected broadcasting trends. This became more visible after the 2011 elections, when political critique became constrained. The growing authoritarianism and networks changing hands from liberal to pro-government owners, impacted television content. 3

Around the same time, the fascination for the Ottoman Empire came into great prominence when a series titled ‘Magnificent Century’ was aired in 2011. The New York Times described it “as a sort of Ottoman-era “Sex and the City” set during the reign of Sultan Suleiman.” While the show was extremely popular in Turkey and the Arab world, Erdoğan was certainly not a fan as he slammed the show for its steamy sequences. Unlike what was depicted in the show, he believed that Suleiman was a brave and adventurous conqueror. In a speech then, he said, “He [Suleiman] spent 30 years on horseback, not in the palace, not what you see in that series” and added that those who “toy with these values should be taught a lesson within the premises of law.” 4

Ever since Erdoğan’s AK Party came to power in 2002, there has been a conscious effort to not just go back to Islamic roots, but also to rehabilitate the Ottoman Empire. The Ertuğrul series was a reflection of that deep seated ambition for prestige and national assertion against enemies. 5

Turkish cultural scholar, Semuhi Sinanoglu, described this strategy as “political technology” and said, “Undoubtedly, each government creates its own political history narrative, and presents its national heroes by choosing them in line with its own ideology. In this context, the Neo-Ottoman TV series on TRT are not only inspired by historical events; it produces consent to powerful nationalist-conservative-authoritarian politics by constructing them specifically, especially in line with today’s politics.” 6

Analysts believe that the success of Ertuğrul has launched a wave of nostalgia and fascination for the era that can be described as “Neo-Ottoman Cool”. Coined by two academics, Marwan Kraidy and Omar Al-Ghazzi, this is reflective of the new image of Turkey that started around 15 years ago. “It demonstrated that shift of perception from Turkey as an enemy to Turkey as a model … Turkish soft power was perhaps at its height with the rise of Erdoğan – this went hand-in-hand with the popularity of Turkish popular culture, particularly Turkish TV series,”7 said Al-Ghazzi.

Senem Cevik, a lecturer in International Studies at UC Irvine, says that the popularity of the show is fascinating. “A show that is produced by a Muslim country, a Muslim regional power is very important, and having those characters in the shows that are powerful, strong, defenders of their nations and their tribes is something I think I would say the Muslim world is looking for.” 8 Hence, there is little surprise that the show has also been a great hit in countries that were either under the Ottoman Empire or Turkey such as the Balkan states.

For Erdoğan and the AK Party, reconnecting with the Ottoman era has been central to their messaging. Television dramas such as Dirilis: Ertuğrul and Payitaht: Abdulhamid – both commissioned by TRT – have aligned well with the party’s communications strategy, as Erdoğan attempts to style himself as an Ottoman sultan and position Turkey as a regional superpower. He has not only visited the set, but the writer and creator of the show, Mehmet Bozdag, is a member of his party. “

They are, in a way, rewriting the Ottoman history for the current Turkish public. They’re trying to showcase a type of history that is continuous from the Ottoman Empire to the current Turkish republic in a way that it elevates the Ottoman history,” says Burak Ozcetin – Associate Professor, Istanbul Bilgi University. 9 “‘Neo-Ottoman Cool’ is directly related with the Turkish Republic’s quest for enlarging its sphere of influence in the region, politically, economically and culturally.” 10

In further steps to exert control over the media, in 2019, the government extended its television censorship rules of prohibiting smoking, drinking or anything that violated Islamic values to streaming platforms as well. It also has more power over dialogue and scenes. This year, the Turkish Parliament passed a new social media regulation law to control various online platforms.

Pakistan’s Islamic Push

Khan’s election campaign in 2018 revolved around the dream of modelling a Naya (New) Pakistan on the 7th century state of Medina. Since then, he has often stressed the need for promoting Islamic values and culture.

In 2019, Khan, in a television interview, while dismissing content from Hollywood and Bollywood, reiterated the need to showcase Muslim heroes and recommended this drama series. “Over here, we go to Hollywood then Bollywood and back again – third-hand culture gets promoted this way”, Khan said. 11

Pakistan and Turkey have a shared history which was reflected in the Khilafat movement in the early 20th century, wherein Muslims from the Indian subcontinent supported the Ottomans. This helped the Pakistan movement as well.

Regarding each other as brother countries, Turkey was amongst the first to recognise Pakistan and had even lobbied for its membership in the UN. Similarly, after the failed coup attempt on Erdoğan in 2016, the-then Pakistani Prime Minister, Nawaz Sharif, was the first foreign leader to contact Erdoğan. Coupled with this, Turkey’s deteriorating relationship with both Europe and the US has led to its deepening bilateral relationship with Pakistan. They have both been part of regional blocs such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and are surrounded by strong neighbours with ongoing conflicts.

The two countries have been trying to develop close economic, political and military cooperation, positioning themselves as an alternate Muslim grouping.

As part of building a cultural proximity between the two, Turkey gifted Ertuğrul to Pakistan as a goodwill gesture. In late April 2020, Pakistan Television via its official Twitter handle announced the airing of the drama series as part of its Ramazan special “on the instructions of Prime Minister@ImranKhanPTI”. Within just two months, more than 58 million people viewed the first episode of Ertuğrul streamed on the YouTube channel.

While the popularity of the show soared, there have been many discussions around the theme of the series. Madiha Afzal, the author of Pakistan Under Siege: Extremism, Society, And The State, says the government’s endorsement of Dirilis Ertuğrul “fits in perfectly with how the Pakistani state has defined its nationalism: based on Islam and on the enmity with India.” 12 “

The reason why the TV show is in Khan’s mind is because he has recently discovered that Turkey is one of the only Muslim countries that has stood up for Pakistan against India and has raised the Kashmir issue,” said Ayesha Siddiqa, a Pakistani analyst and author. “There is a historic fascination with Turkey being the only country where Pakistan gets respected.” 13 “There is also a pan-Islamic historical fascination which was there in Pakistan historically but has now started to resurface,” Siddiqa added. 14

However, there are scholars who believe that the drama series might not achieve its purpose of countering anti-Islamic sentiments. They believe that Islam can be represented positively in other ways. Said Pervez Hoodbhoy, “Perhaps overwhelmed by Erdoğan’s aggressive style, Prime Minister Khan proudly tweeted that Turks had ruled India for 600 years. Historians will raise their eyebrows — this is between quarter-true to half-true only. But it must be rare for a prime minister to hail imperial rule over his land.” 15

The quest for Pakistaniat (Pakistani identity) led the country to earlier adopt Saudi culture under General Zia-ul Haq, and now Turkish under Khan. However, the middle-class, which is Khan’s political base, seems to have connected with the version of Islam depicted in Ertuğrul, which is reflected in the large viewership.

Soft Power to Strengthen Ties

While Ertuğrul has gained popularity in many parts of the Muslim world, some Islamic organisations such as Egypt’s Dar al-Ifta al-Misriyyah (one of the Middle East’s oldest and most influential bodies responsible for issuing fatwas or religious edicts) claims Erdoğan has “sinister plans” to influence the Arab world and eventually conquer them and, thus, should

. . . . .

*About the author: Ms Nithya Subramanian is an Editor at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). She can be contacted at [email protected]. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Source: This article was published by Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS) as ISAS Insight