Peace-Building From The Bottom: A Case Study Of The North Caucasus

By CRIA

By Huseyn Aliyev for CRIA

The collapse of the USSR has left the North Caucasus, a region in the south of the Russian Federation, in a quagmire of disputes among its multiple freedom-aspiring ethnicities and the newly born Russian state. In spite of almost two decades of violence in the region, it continues to remain a “forgotten crisis”, even more so than it used to be in the 1990s, when the region arguably received more media attention. According to Human Rights Watch, in 20091 the separatist insurgency in the North Caucasus intensified, and a 2009 Crisis Watch report (ICG 2009)2 identifies the region as an ongoing conflict area. With this in mind, this paper analyses the prospects for peace-building in the North Caucasus.

Increasing Violence: The 2000s

The end of large-scale fighting in Chechnya (in 2002–3) was in fact the beginning of the conflict’s spillover in the North Caucasus. The adoption of the Chechen constitution by the Russian-backed government of Ahmad Kadyrov in 2003 and Kadyrov’s being elected as president of the Chechen republic officially put an end to Chechnya’s independence and outlawed the separatist government of Aslan Maskhadov.

The outflow of fighters from Chechnya, from 2002–3, gave a powerful boost to the development of insurgent cells in different parts of the region. The first indicator of conflict spillover was a rapid increase of attacks on government officials, security forces and military installations throughout Dagestan, Ingushetia, North Ossetia, Kabardino-Balkaria and Karachay-Cherkessia. Although sporadic incidents of violence took place in different areas of the North Caucasus outside Chechnya prior to 2002–3, it has been in the majority of cases masterminded and conducted by Chechen militants rather than by home-grown insurgencies. For instance, Dagestan has long been a scene of the conflict due to frequent Chechen cross-border raids even though prior to the end of large-scale military operations in Chechnya it had no active insurgency of its own. A new type of conflict began to emerge in the North Caucasus between 2004 and 2006, in which most of the violence has been perpetrated by the so-called military jamaats:3 home-grown and mostly autonomous insurgent groups operating in the North Caucasian republics. The data compiled by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) indicates that as early as January 2004, Chechnya ceased to be the only “hot spot” in the North Caucasus, and it was no longer the most violent place in the region.4

On October 2007 Doku Umarov announced the creation of a “Caucasus Emirate” (Imarat Kavkaz).5 The Caucasus Emirate has eliminated the concept of independent Chechnya, instead replacing it with that of a united pan-Caucasian state, including all of the Russian North Caucasus. Although opposed by some of Ichkeria’s leaders in exile,6 the Caucasus Emirate has opened a region-wide front of anti-Russian insurgency. As a result, the rates of violence almost doubled in 2008, and tripled in 2009. Indeed, a surge of violence in 2009 meant conflict had reached unprecedented levels, with 1,100 incidents that year in comparison with 795 in 2008. The number of people killed in conflicts almost doubled in 2009, with 900 fatalities compared with 586 deadly incidents in 2008.7

Paradoxically, in April 2009, Russian President Medvedev’s administration announced an end to “counter-terrorism” operations in Chechnya.8 The announcement was more symbolic than anything, essentially needed to provide a boost for Ramzan Kadyrov’s government. According to the latest data,9 the first four months of 2010 have already seen more than 200 conflict-related deaths, with the majority of violent incidents occurring in Ingushetia and Dagestan (109 in Ingushetia and over 90 in Dagestan). In spite of the increase in hostilities, there have been no attempts to initiate peace talks (as of fall 2010) between the state and the insurgents. Moreover, the federal government actively denies the very existence of an ongoing armed conflict in the North Caucasus and rejects any necessity for conflict resolution and peace-building. The situation in the North Caucasus is officially defined by the president of the Russian Federation, Dmitry Medvedev, as a “struggle against terrorism.”10 After the cancellation of “counter-terrorism” operation in Chechnya in April 2009 (started in August 1999), the president emphasized “the clear improvement of the situation in North Caucasus” republics’ and concluded that “Russia’s fight with terrorism has been successful.”11

Theory of Bottom-Up Peace-Building Revisited

A bottom-up peace-building approach, also known as “indigenous empowerment”, is a comprehensive tool in the conflict resolution field. A core idea of bottom-up peace-building is to empower local populations at the bottom and mid-levels of society by allowing them to consolidate and develop necessary resources for the implementation of a peace process, which could be later advanced onto elite levels.

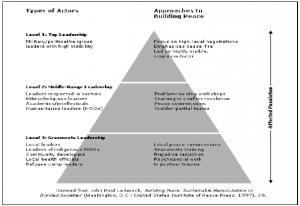

Lederach’s pyramid of peace-building (see Figure 1) reasonably places NGOs and other civil groups into the mid level so as to represent a link between elite/state and people/grass-roots. According to Lederach (1997), the reason why bottom-up peace-building efforts can be more efficient than those originating from the top is that

by virtue of their high public profile […] leaders are generally locked into positions taken with a regard to the perspectives and issues in conflict. They are under a tremendous pressure to maintain a position of strength vis-à-vis their adversaries and their own constituencies.12

Middle-range actors are usually not involved in the governing process. In general, they are educators, intellectuals, businessmen and representatives of civil society. However, they can have a certain degree of influence on the elites while simultaneously serving as a link between the state and the population. Most importantly, middle-range actors should have no political or military affiliations. And although they do not necessarily have to be neutral, they, nevertheless, are not expected to support either side openly. Accordingly, middle-range leaders do not usually “depend on visibility and publicity”.13 In the case of the North Caucasus, middle-range actors can be representatives of local and international civil groups, community leaders, village elders, intellectuals, scholars and, in some cases, clan leaders. However, the exact definition of middle-range leaders needs to be more precise in each particular case. For instance, in Dagestan, where those of Avar ethnicity traditionally occupy governmental posts, many Avar clan leaders might be expected to have links with authorities or occupy certain positions in government. However, many of Dagestan’s insurgents are also of Avar ethnicity. In such cases, it might be reasonable on rely on middle-range leaders from civil society rather than on community or clan leaders. The same might be said of Kabardino-Balkaria, where those of Kabardin ethnicity form the ruling group, and Kabardins are also a major recruitment pool for rebels. In Ingushetia, clan leaders as a rule are in charge of municipal or district administrations and are less trusted than elders and grass-roots leaders without clan affiliation.

Lederach (1997) also places religious leaders into a middle-range category. That might have a dubious role in the case of North Caucasus. Most of the religious establishment in the region is closely associated with the government; it supports authorities and receives backing from elites, both local and federal. Sufi religious leaders are seen by the government as a bulwark of moderate Islam and a counter-balance to radical Salafi separatists. However, popularly Sufi clerics are often regarded as corrupt and as using religion to legitimize local authorities with no respect for traditional notions of Islam. Thus, by adhering to Salafi branch of Islam, rebels and critics of the state deny clerics’ power of religious authority. The so-called hunt for Wahhabis,14 unleashed by Putin’s administration in the North Caucasus, along with the start of the Second Chechen campaign (launched in 1999), in fact, allowed Sufi clerics to strengthen their position and eradicate their opponents from other branches of Islam.15 However, considering that many rank-and-file members of the insurgency as well as some of its commanders are still followers of the Sufi branch rather than radical Wahhabis, it might be expected that the emergence of neutral Sufi clerics could be favorable for any peace process.

Indeed, the middle-range actor category also includes the leadership of the insurgents. In comparison with such rebel movements as the Tamil Tigers and Angola’s UNITA, which have the whole decision-making and leadership process concentrated in the hands of a “supreme leader” whose death would cripple the struggle, the insurgency in the North Caucasus has a rather dispersed power-center. The rebel movement’s leadership is constantly undergoing staff turn-over, with newly emerged leaders replacing deceased ones. Also, in contrast to former and current Chechen warlords, insurgency leaders in other parts of the North Caucasus prefer to stay in the shadows and rarely appear in the headlines. It has been speculated, for instance, that as head of the Caucasus Emirate, Doku Umarov has only a nominal power over insurgent jamaats (organizations) outside of Chechnya.16 In general, most of the insurgent leaders in Ingushetia, Dagestan and Kabardino-Balkaria are from the middle class rather than from the republics’ elites.

However, in spite of middle-range level’s importance, Lederach (1997) allocates a leading role in peace-building to grass-roots leadership, i.e. members of NGOs working with local communities, health care personnel and grass-roots volunteers at the community level. As Lederach observes:

[…] the local level is a microcosm of the bigger picture. The lines of identity often are drawn right through local communities, splitting them into hostile groups. Unlike many actors at the higher level of the pyramid, however, grassroot leaders witness first hand the deep-rooted hatred and animosity on a daily basis.17

Lederach also implies that most of the social issues, such as human-rights abuses and inter-ethnic divisions, often start at the grass-roots level. Accordingly, the actions taken by leaders of the state are slow to reach their actual beneficiaries at the bottom of pyramid, i.e. grass-roots community levels. By contrast, activities conducted from the bottom-up are more likely to be aimed at the actual needs and grievances of the affected population. Regarding the ongoing conflict in the North Caucasus, it is obviously the level of social insecurity and the inability of civil society to fulfill its role that affects the issue. The conflict’s distinctive feature is that it has clan members and representatives of multiple ethnicities rebelling against their leaders and the establishment that they support rather than rallying along ethnic and national divisions, similar to past conflicts in the Caucasus. The incompatibility begins at a grass-roots level sometimes overtaking middle levels of society but never the upper ones. Thus, the classical models of peace-building18 which aim to identify the top leaders and bring them to a negotiating table for peace talks is less plausible in the North Caucasus. As mentioned earlier, insurgency in the region does not have a clearly defined leadership capable of ordering all the groups to cease fighting; the leadership is dispersed, symbolic in nature and constantly changing. Moreover, in contrast to societies in “old wars”, where rebel leaders often attempted to represent the whole population and pursued higher goals, such as independence from colonialism, or the struggle against capitalism, dictatorship or ethnic liberation, insurgent leaders in the North Caucasus hardly even have clear and feasible objectives for the struggle. Apart from that, top-level peace-making has previously failed in earlier conflicts in the North Caucasus, in the first Chechen war in particular. It must also be noted that in comparison with the “old wars”, where the top-level peace-building has mostly been used before, both of the conflicting sides in the North Caucasus have reached the stage when mutual vilification makes it extremely difficult even to start peace talks.

Middle-range peace-building has a better potential for success in the North Caucasus. Lederach (1997) identifies a number of major activities as a part of middle-range conflict resolution, e.g. problem-solving workshops, conflict-resolution training and peace commissions. The main goal of these activities is to initiate contact and dialogue between middle-range leaders representing civil society and the conflicting sides. Such workshops or meetings are normally conducted off the record and are designed to lead to further dialogue at higher levels. The 1993 PLO–Israeli accords and the 1996 Guatemala accords are usually cited as outcomes of such informal problem-solving meetings. Conflict-resolution training can be understood as an element of a middle-range peace-building. The training is expected to be conducted by leaders of civil society and community representatives in order to raise awareness of peace and reconciliation. In general, middle-range peace-building activities may take many different forms directed at changing perceptions, stereotypes and incompatibilities of the warring sides.

In spite of the importance of middle-range peace-building, it is bottom-up, grass-roots action that is expected to serve as a decisive force in enforcing a peace process. In fact, grass-roots actors are most of all in need of peace because it is they who have to cope with ongoing violence in their daily lives.19 Lederach (1997 & 2001) concludes that it is desperation and frustration with the conflict that usually force grass-roots actors onto the pass of promoting peace. However, in order for bottom-up peace-building process to start, it is necessary to “empower” local actors by ensuring them of the feasibility of peace efforts and of the plausibility of conflict resolution. Such an empowerment is generally considered to be the job of NGOs and civil society. It is non-governmental actors, from both middle-range and grass-roots, who can arguably be responsible for initiating dialogue, “empowering” themselves and local communities at the same time. Active and vocal civil society is a necessary prerequisite for the implementation of bottom-up peace-building. Advocates20 of the bottom-up approach claim that most modern civil wars of the “new type”, i.e. conflicts between state and non-state actors or civil wars between two or more non-state actors, have ended as a result of bottom-up peace-building.

Peace-building is also often associated with society-building, which is usually the case in post-colonial societies and societies in transition. Society-building has become a necessity in many post-Soviet states in the early 1990s in the aftermath of the collapse of USSR. That process has also engulfed the North Caucasus. However, society-building in Dagestan, Ingushetia and Kabardino-Balkaria was not as clearly shaped as in the independent states of the Caucasus. In comparison with Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, where society-building evolved around rising nationalism and ethnic identity, a similar process in the Russian North Caucasus (with the exception of Chechnya) has been largely focused on economic transition from industrial and agricultural industries to service-oriented industry and tourism.

Civil Society in Bottom-Up Peace-Building

At first sight it might be rather difficult to access the effectiveness of NGOs’ role in peace-building. Whereas the proponents of peace-building from the bottom strongly advocate the idea of empowering local groups and communities, others are either wary about the role of NGOs in an armed conflict21 or cautious about the level of NGOs’ engagement.22

Yet another debate focuses on whether global civil society is more efficient in peace-building than local. The proponents of the global approach claim that, on average, national NGOs tend to work on peace-building at macro levels, targeting elites and the state,23 whereas supporters of the local peace-building24 state that international NGOs often attempt to bring Western ideas of peace-building and disregard local needs and traditions. Anderson and Olson (2003) also add that:

Agencies with experience in many conflicts can create the impression that they are the experts in peace. This can disempower people who have experience in only their own conflict. It can undermine local people’s energy and initiative to act. In some cases, peace agencies inadvertently communicate the implicit message that local people cannot make peace without their outside help.25

Generally speaking, it is very difficult to present NGOs as either a positive or a negative actor in bottom-up peace-building. Examples from different parts of the world offer diverse techniques used by civil actors in implementing. Varshney (2001) in his study on civil networking at grass-roots level and their influence on inter-ethnic conflicts in India concludes that civil society does matter in reducing inter-ethnic tensions via grass-roots networks incorporating members of different ethnic groups.26 He argues that associational and everyday forms of civic engagement have served as a balance in inter-ethnic and inter-confessional conflicts in different parts of India. Civil society’s involvement in peace processes in the Philippines has been considered a success,27 leading to peace agreements between the government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). Due to the active participation of grass-roots groups, religious leaders, local and international NGOs, it has become possible for civil society to influence conflict participants by elevating the root causes of conflict from grass-roots to elites. However, Toohey (2005) emphasizes that if NGO interventions “are not accompanied by meaningful government redistributive policies and political reform, then it is likely that their constituencies will become increasingly disillusioned with the promises inherent in the struggle for peace.”28

Successful examples of bottom-up peace-building can be found in the 1998 Angola peace process and the 1994 Guatemala peace talks. Palestinian civil society also has a long history of involvement in peace-building and is known to have won a number of achievements in peace talks with Israel. The above-mentioned 1998 Angola peace agreements as well as the Nuba Mountains Ceasefire in Sudan are examples of a successful third-party-initiated, bottom-up peace-building. In both cases peace processes have been monitored by the international community with a strong focus on local participation.

On the other hand, Ramirez (2008) suggests that civil society’s involvement in the Colombian civil war so far has had limited success. She argues that even in times of active NGO participation in peace processes between leftist guerillas and the government, levels of violence have had little correlation with levels of civil engagement.29

Such claims support Kalyvas’ (2006) theory which states that levels of violence “persisting across time and space” are mere reflections of armed groups” struggle over territorial control.30 Accordingly, in areas where such control is contested, levels of violence are high. By contrast, areas where an armed group (or the government) has established firm control over a given territory, levels of violence are the lowest. However, this theory can hardly serve as an explanation for the escalation of violence in the North Caucasus. Being a territory controlled by the federal government in Moscow, the North Caucasus keeps plunging deeper into violence. Contrary to Kalyvas’ hypothesis, the Russian government is in physical control of the territory in North Caucasus, with no areas under the control of the separatists, a fact which to some degree can be a cause for the conflict.

Bottom-up peace-building has been widely used in Somalia, although with different outcomes. Active grass-roots involvement in the 1991 peace agreements in Somalia, described by Lederach (1997) as a successful case of the bottom-up approach, included the participation of clan leaders and elders and contributions from many communities and ethnic groups. Another successful application of bottom-up peace-building in Somalia is a peace-process and governance building in Puntland from 1991 to 2007,31 which lead to the creation of the Puntland administration supported by clan leaders and local communities. However, the bottom-up peace attempts have been of little success in Mogadishu area, as well as in other parts of the country after the end of UN intervention in 1992.

Apart from Colombia and Somalia, Sri Lanka can be cited as one of the failed examples of bottom-up peace-building. Harpviken and Kjellman (2004) mention Sri Lankan civil society’s lack of impartiality as one of the main reasons for its failure to serve as a bridge between the government and the Tamil Tigers.32 International organizations likewise failed to achieve considerable results in the Sri Lankan peace-building process, mostly due to the distrust of the Tamils and the unwillingness of the government to cooperate. Afghanistan is often mentioned as an example of a successful empowerment of local civil society in the early stages of post-9/11 reconstruction.33 Bottom-up peace-building exercised in a form of empowering tribal shuras, or village councils, is presented as a success which resulted in driving the Taliban out of many tribal areas in the north of the country. However, recent developments in Afghanistan seem to prove that bottom-up empowerment can be a short-lived success in an absence of human security in the long term.

Retrospectively, it is difficult to single out bottom-up peace-building as the most successful type of implementing peace, or to brand it as a failure. It has seen both successes and failures in a variety of conflicts around the world. However, in a modern political arena dominated by conflicts of the “new type”, i.e. intrastate civil wars, the bottom-up approach reaches to the very core of a conflict – the population, or the grass-roots. Some of the above-mentioned cases of the bottom-up theory application in practice are similar to the North Caucasus, whereas others are too different. For instance, similar to Sri Lanka, civil society in the North Caucasus lacks impartiality and keeps at a distance from insurgents, who often portray it as state-controlled, in particular such elements of civil society as the religious establishments and charity groups. The North Caucasus conflict also resembles the conflict in Mindanao, Philippines, where peace-building efforts required not only inter-ethnic but also inter-confessional dedication. And similar to Afghan civil society, civil grass-roots in the North Caucasus are weak and in need assistance. In spite of the existing proximities and discrepancies of peace-building approaches around the world, it is necessary to consider the uniqueness of each case study and the difficulty present in attempting to replicate successes and avoid failures. The most significant lesson to be drawn at this point is that bottom-up peace-building can solve conflicts: it deals with local communities, mobilizes local peace-building potentials, requires the participation of civil society and welcomes the collaboration of national and international civil groups. A set of examples presented in this section also aims to illustrate that the bottom-up approach does not require NGOs, grass-roots movements and other elements of civil society to be highly developed and sophisticated. However, it does require civil society to be independent from the state and capable of acting as a “third” sector, balancing between the state and people or, in other words, capable of fulfilling its function as a civil society. Therefore, it might be useful to examine how successful the practice of empowering local actors has been in the North Caucasus thus far.

Bottom-Up Peace-Building Practice in the North Caucasus

After a brief overview of bottom-up peace-building practice around the world it might be necessary to scrutinize the history of peace-building efforts in the North Caucasus. Peace-building as such is not new to the region, and the bottom-up approach has been used previously in the North Caucasus. In spite of being applied in different contexts and settings, previously used approaches can nevertheless be of some help to future peace-builders.

Bottom-up peace-building began with the start of the first Chechen war as early as in 1995. Grass-roots peace efforts were mostly focused on ceasefire negotiations and prisoner exchanges, and were implemented mainly by national NGOs. The most prominent group initiating informal talks with Chechen field commanders and working on community-level peace-building was the Committee of Soldiers’ Mothers of Russia (CSMR).

Committee of Soldiers” Mothers of Russia (CSMR)

Organization’s Profile:

“Committee of Soldiers” Mothers of Russia (CSMR) founded in 1989, as a grass-roots movement, works on peace and non-violence, implementation of civil accountability and transparency of federal and municipal administrations and the development of civil society and civil consciousness in Russian Federation. With the start of war in Chechnya in 1994, CSMR actively worked on the protection of conscript’s rights, exchange and release of prisoners of war and hostages. In 1996, CSMR received “Right Livelihood Award” for its contribution to peace and civil development.

Source: CSMR official website, http://www.ucsmr.ru/english/.

CSMR volunteers managed to organize massive prisoner exchanges and secure releases of captured Federal soldiers and officers.34 The successes of CSMR can be attributed to their “straightforward” approach of directly contacting Chechen warlords and village elders rather than negotiating prisoner exchanges via the top command of both the federal and Chechen sides, which could be less successful and could take more time. Mostly elderly female CSMR volunteers managed to vouchsafe free entry into rebel-controlled areas and establish trust-based contacts with rebel commanders on the ground. After the end of hostilities in 1996, CSMR’s work has been continued by another Russian grass-roots group, the “Peacemaking Mission of General Lebed” (PMGL).

Organization’s Profile:

The Peacemaking Mission of General Lebed (PMGL), founded in 1998 by Gen. Alexander Lebed as “Peace Mission in the North Caucasus”. The group works on prisoner release and exchange as well as the release of hostages and illegally detained persons.35 It claims to have released over 200 prisoners and hostages in Chechnya since the start of its work in 1998.36 According to the group’s mission statement,37 one of its main priorities is conflict prevention and the de-escalation of violence in the North Caucasus.

The Peacemaking Mission of General Lebed (PMGL)

Source: PMGL and FEWER.

Although both CSMR and PMGL are still active in the region, it is obvious that their previous peace-building successes have been achieved in an environment different from the current one. Precisely speaking, both of these grass-roots groups have worked in an environment of large-scale military activities, almost unobstructed by the state, capable and willing to engage the rebel side in Chechnya, which remained their main partner. Both groups have also deployed typical bottom-up approaches of reaching out to minor Chechen warlords or clan and village elders in an informal way. Generally, throughout the whole Chechen conflict, Chechen warlords operated in a locality of their origin, i.e. village, town, settlement. Accordingly, they drew their recruits, food and supplies from such a locality and closely depended on it. Therefore, community peace-building could potentially succeed in such an environment.

The current conflict, on the other hand, is more of a type of guerilla warfare without clear-cut frontlines, where insurgents do not control any areas and only have basic contacts with the local population in rural and urban areas. The composition of insurgent groups has itself changed significantly from locally recruited Chechen warlords’ bands. Now a typical profile of an insurgent recruit can be presented as follows:

He or she is young—in the 18-20 age range—and almost always a college student, often away from home. They might be a student in Moscow or in one of the Western countries or, on rare occasions, a student at an Islamic institute in the Middle East. Whatever the case, he or she is a young person who is only about to begin an independent life; a person who is easily attracted to the idea of comprehending the truth and distinguishing it from untruth.38

It is known that insurgents are receiving continuing support from the local population.39 However, most of the insurgent jamaats are fairly autonomous from the local population; they receive recruits (predominantly from urban populations) handpicked by the jamaats’ operatives, who are normally not connected to local communities and are not subjects to elders or community leaders. In terms of their supply links, insurgents seem to be more prone to rely on “institutionalized” methods of food and supplies collection rather than on donations from communities in their localities.40 Another source of insurgent logistics is mentioned by Vatchagaev (2009):

Whether or not there are shared ideological views, any interaction with relatives who happen to be militants is governed by the mechanism of highland ethics that is inherent in all Caucasian peoples. It implies that if a person invokes a name of a relative, then to assist him or her is not simply an obligation but also a matter of personal honor.41

In addition, on a number of occasions the local population involved in the rebel “food supply chain” has been either financially or forcibly convinced by federal forces to poison rebels.42 Thus, trust between the local population in rural areas and the insurgent groups operating there is not of the same level as in previous Chechen conflicts. Therefore, groups such as PMGL, who based their work on first establishing links with local communities and through them extending their reach to rebel commanders, might experience difficulties in achieving their goals.

Furthermore, in comparison with the Chechen wars of the 1990s, the current conflict requires slightly different peace-building priorities and goals. There is no longer a need for prisoner and hostage release from the rebel side; most of the missing persons are now allegedly held by security forces.43 In comparison with the aftermath of the first Chechen war, i.e. the period from 1996 to 1999 when hundreds of civilians were kidnapped in Chechnya and outside it by armed Chechen gangs, mostly made up of former rebels, most of the kidnappings are now conducted by police, the Special Forces and other law enforcement agencies. Moreover, grass-roots peace-builders of the 1990s seem to have prioritized short-term activities, e.g. prisoner release and exchange, over long-term goals, such as community peace-building, conflict cessation and the eradication of war culture. The dynamics of the current hostilities, however, dictate prioritizing long-term goals in the first place. Cessation of hostilities seems to depend now on the government’s policies and the shift in both republican and federal policy-making rather than on the dissolution of rebel forces. In terms of community peace-building, there is a lot more to do now than in 1990s Chechnya; it is necessary for peace-builders to establish contacts with rebel commanders. And that might be as important as peace-oriented community work in areas of rebel activity. However, a personal approach, actively used in 1990, is also a must. Similar to the conflicts of the 1990s, insurgent forces do not have a “supreme” leader with whom to negotiate, and, therefore, approaching individual field commanders remains necessary to achieve peace. Evidently, a new peace-building approach needs to incorporate some activities of earlier peace-building efforts in cohesion with new strategies.

In general, with the regard to previous grass-roots peace-building experience it is possible to identify a number of priority areas for peace-builders. First, peace-building has to target wide circles of the population, starting with the grass-roots, i.e. the current and potential rebel recruits, supporters, sympathizers as well as the local population in areas of insurgent activity. It is necessary to ensure that peace-building efforts are directed at those most affected by the conflict, i.e. the civilian population. Second, peace-building has to include not only the rebel forces but, most importantly, the security and military of the North Caucasus republics, as well as similar structures at the federal level. As mentioned earlier, the growth of authoritarianism and its onslaught against civil society, accompanied by centralization and militarism, are presented here as some of the main reasons for the current escalation of violence. Decentralization and demilitarization of local and federal governments might be considered as long-term objectives to de-escalate the conflict. Working with the police and law enforcement agencies is necessary to prevent human-rights violations, which are known to fuel conflict and increase the distrust of the population toward the government. The improvement of the human-rights situation should be given priority in eradicating the root causes of conflict, the insecurity of the population and the heavy-handed treatment by police and law enforcement. However, although current peace-building efforts in the region are limited in their scope and nature, some bottom-up activities are still taking place.

Current Efforts of Bottom-Up Peace-Building in the North Caucasus

There are a handful of peace-building programmes operating in the North Caucasus. A brief analysis of their activities presented below may help to understand the pitfalls of the current peace efforts.

Nonviolence International (NI) peace-building

Organization’s Profile:

“Nonviolence International promotes nonviolent action and seeks to reduce the use of violence worldwide. Nonviolence International is a decentralized network of resource centers that promote the use of nonviolent action. NI is also a non-governmental organization in Special Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations.”44 It was founded in 1989 by a Palestinian activist and is registered in Washington D.C., USA. It runs projects in Indonesia, Palestine, South America, the former Soviet Union and Southeast Asia.

Non-violence International

Source: Nonviolence International, http://nonviolenceinternational.net.

A multi-sector peace-building programme launched by an international NGO Nonviolence International (NI) on the territory of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) in 1993 was expanded to the North Caucasus in 2001.45 Nonviolence International in the CIS (NIS) began its peace-building efforts in the republic of Karachay-Cherkessia and the border regions between Chechnya and Dagestan. Its main goal is conflict prevention and de-escalation as well as reconciliation and rehabilitation in conflict-affected societies. The NIS peace-building programme focused on conducting peace trainings to youth in remote regions of Dagestan and Ingushetia. In 2001–2, NIS launched a number of programmes designed to increase inter-ethnic reconciliation and peace-building in the border regions of Chechnya and Dagestan. These programmes aimed to reduce tensions between Dagestani and Chechen villagers in the border regions after the invasion of some border districts of Dagestan by Chechen-led Islamist Brigade in 1999 (which served as the start of the Second Chechen campaign). Two separate programmes have been also implemented in Karachay-Cherkessia and Kabardino-Balkaria. Both had as their goals to increase inter-ethnic tolerance and conflict prevention in the multi-ethnic settings.46 NIS defines its peace-building priorities as:

Any humanitarian, human rights, cultural, sports, analytical, educational and/or other activity implemented then and there, when and where it can practically influence a situation in the direction of preventing violence, mitigating tensions and managing conflicts between self-identified groups of population.47

According to the data provided by the Nonviolence International group, most of its funding, used to implement peace-building programmes in the North Caucasus, is from private sources.48

In 2005 NIS launched the North Caucasus Regional Peace-building programme.49 The programme was intended to cover almost all of the Russian North Caucasus and its primary goals are peace-building, regional development, inter-ethnic and inter-confessional tolerance. It also defines republic-specific goals. For instance, in Kabardino-Balkaria it identifies as a priority the participation of young people in social and political life of the republic. It also includes training courses and seminars on non-violence and tolerance as well as the promotion of education and employment. In Dagestan it prioritizes inter-ethnic cooperation and tolerance to Chechen IDPs, as well as inter-confessional reconciliation between the Sufi and Salafi adherents of Islam. The programme pursues similar goals in Ingushetia.

Most of the peace-building activities implemented as a part of the programme are sport competitions, culture and socializing clubs, peace education programmes, training courses and discussion clubs. Notably, almost all of the NIS activities took place in rural areas. Generally, the NIS work can be described as local capacity-building. However, its scale and degree of penetration into the society are insufficient to bring long-term results in peace-building. First, the majority of NIS programmes are focused on inter-ethnic relations and tolerance, which are not the causes of the current conflict. Second, considering that a great degree of violence and human-rights violations are conducted by the law enforcement and state authorities, NI does not have programmes dealing with such issues as abductions, torture and extra-judicial executions often practiced by law enforcement as a part of “anti-terrorism” campaigns. Third, in comparison with PMGL and CSMR, the NI does not establish links with insurgents, which limits its opportunities at implementing a long terms peace.

Peacebuilding UK and the rest

Organization’s Profile:

“Peacebuilding UK’s mission is to support and build local capacities for peace in the Russian Federation, predominantly in the North Caucasus region. This involves supporting and jointly implementing projects with staff, local groups and individuals in the region to promote sustainable peace, well-being and the enjoyment of human rights, with a particular focus on children, youth and other vulnerable people.”50

Peacebuilding UK

Source: Peacebuilding UK, http://peacebuildinguk.org/home.

Peacebuilding UK began operating in the North Caucasus in 2006. Currently it runs two programmes in six republics, including Dagestan, Ingushetia and Kabardino-Balkaria. Peacebuilding UK mostly focuses on cultural and social programmes, psychological rehabilitation and peace-building networking.51 Funded and supported by the Russian Charitable Fund, the group also conducts conflict resolution and conflict transformation trainings in the North Caucasus and Russia. It must be said that Peacebuilding UK also actively works at the grass-roots level by engaging in the daily lives of local communities and promoting their focus on culture and self-identity. Apart from peace activities, the group also works on the reconstruction of infrastructure, mainly of educational and cultural facilities, and particularly in Chechnya.52

“Humanitarian Dialog for Human Security in Chechnya” is a peace-building project implemented in Chechnya in 2005 by FEWER International, in association with swisspeace. The project focused on bringing the conflicting sides together for negotiations on non-political subjects, e.g. issues of psychological rehabilitation, reconciliation, release of illegally detained persons and enhancement of human security aimed at increasing the effectiveness of humanitarian operations.53 Unfortunately, the project was meant to bring together only local/federal officials and representatives of Chechen civil society without directly reaching out to the separatists. The project also promoted strengthening the rule of law and state institutions, which meant the delegation of more power to the Kadyrov’s clan. However, strengthening state institutions in the North Caucasus, and in particularly in Chechnya, often means the allocation of additional authority to corrupt state officials (as in the case of Ingushetia) or autocratic strong-men (as in Chechnya) rather than the promotion of democracy.

Yet another peace-building programme worth mentioning is a UNICEF-run peace education programme. Focused on children and youth, the programme conducts regular summer camps for peace education, distributes materials and disseminates knowledge and conflict awareness.

A couple of other NGO initiatives have been implemented in the region with the goal to boost peace-building initiatives, namely by the NGO “Friendship–North Caucasus” and the Russian NGO Intercentre. The NGO “Friendship–North Caucasus”, created in 1997, works on multi-ethnic tolerance and reconciliation. It is also one of a few local civil groups engaged in peace activities. In 2007, the NGO started a programme called “Cooperation in ethnological monitoring implementation and early conflict prevention”. Based in Stavropol, it is mostly active in the North-West Caucasus. A two-year project entitled “Cross-Cultural Understanding and Peace in the North Caucasus”,54 has been launched by the Russian NGO Intercentre, founded by the Open Society Institute (OSI) and aimed at promoting peace education and non-violence in elementary and high schools in all the republics of North Caucasus.

Top-Down Efforts

Amid the ongoing human insecurity crisis, the government of the Russian Federation also took note of the need for peace. In spite of stubbornly adhering to Putin’s ideology of “no talks” with the underground rebels, denying the very existence of conflict in the North Caucasus and branding all anti-Russian resistance as international terrorism, Medvedev’s administration has nevertheless made a few short-lived attempts at peace-building.

Worth mentioning is the “Peace to the Caucasus” project, which was brought to life by a pro-Kremlin journalist, Maxim Shevchenko, and has been described by state officials as “one of the last hopes for the North Caucasus for improvement.”55 Launched in October 2009, the project attempts to initiate dialogue between state officials and representatives of civil society in the region. To distinguish it from a purely top-down initiative, the project also considers talks with community leaders and grass-roots organizers. Although it is difficult to brand the “Peace to the Caucasus” as a complete failure at the moment, it has already been pointed out that the project has not yet moved from the “talking” stage (as of spring 2010). According to a well-known Dagestani sociologist, Enver Kisriev, “There were hearings; no decisions were made, various suggestions were moved; and everybody was [invited] to take further part in drafting the report in the Northern Caucasus.”56 Limited in its scope to a discussion project and with no attempts to communicate with the population or with militants, it seems obvious, that “Peace to the Caucasus” is not aimed at bringing any concrete results apart from emphasizing its own existence as a “peace effort” brought over by the state and civil society (represented by Maxim Shevchenko).

“Peace to the Caucasus” remains the first top-down peace effort which aimed to cover the whole Caucasus and not only Chechnya. It is important to mention that since the start of conflict spillover in the region both local and federal authorities have hardly ever tried to implement any peaceful conflict resolution measures at all.

Amnesty to rebel fighters in Dagestan announced in February 2010 by the newly appointed president of Dagestan, Magomedov, was one of a few attempts at reducing violence through non-violent means.57 The outcome of that amnesty has never reached the press and its results remain unknown for the moment (as of August 2010). However, considering the Chechen experience of amnesties, during which many of the former insurgents who chose to hand over their weapons were later abducted or subjected to continuous harassment from law enforcement,58 it is doubtful that amnesties can work in the absence of human security and law and order.

Conclusions

In retrospect, most of the current peace-building efforts in the region are failing to bring the conflict participants, i.e. the insurgents and the federal government, to the negotiating table. They also fail to address the root causes of violence, in particular the grave violations of human rights conducted by law enforcement forces against civilians, systemic corruption and a lack of transparency and accountability on the part of state officials and institutions. Moreover, the majority of these peace initiatives are failing to accept that the region remains a scene to an ongoing armed conflict. Instead, most of the projects are of a post-conflict nature, focusing on inter-ethnic communication and social and cultural activities.

The bottom-up peace-building has been used before in the Caucasus, has the potential to be used again and can be a solution to the ongoing conflict. However, a review of the current peace efforts in the region shows that both top-down and bottom-up peace activities are far from targeting their goals and equally far from reaching positive outcomes. In the meantime, both the international community and the local and federal authorities are realizing the gravity of situation in the region and slowly, and to some extent reluctantly, are starting to conceive of peace efforts. It is obvious that top-down peace-building can have little success in the current conflict: the Russian government simply would not find credible counterparts on the insurgent’s side to start talks and guarantee the end of violence. Moreover, the state under the current government has no desire to acknowledge the very existence of an armed conflict in the North Caucasus, which makes any possibility for top-down peace-building impossible.

The bottom-up approach, by contrast, might have a brighter future. As we have seen from the past experience of NGO engagement in local empowerment and bottom-up peace activities in earlier conflicts in Chechnya, civil society can help to tackle the problem. However, the lack of such a civil society at the present moment poses a different problem. The current peace-builders in the North Caucasus, be it NIS or Peacebuilding UK, are obviously not entirely enough to change the situation on the ground. A brief analysis of the conflict shows that efforts of post-conflict transformation and reconciliation are too premature and inter-ethnic tolerance and empowerment of state institutions are not directed at the root causes of violence, e.g. the infringement of civil liberties and freedoms as well as ongoing abuses of human rights. The current peace activities undertaken by the above-mentioned NGOs, at first glance, resemble a humble effort in a chaos of an armed conflict. Although both the NIS’s and Peacebuilding UK’s programmes are aiming at grass-roots conflict resolution, they do not engage the actual participants of the conflict: insurgents and law enforcement and state officials. Considering the dynamics of ongoing conflict, particularly that it is neither a rural or urban conflict nor an ethnic or nationalist one, bottom-up peace-building has to be directed at wider masses of the population.

To sum up it is necessary to emphasize that bottom-up peace-building can bring positive changes to the region only if its proponents are willing to consider a number of essential criteria for the success of peace efforts in the North Caucasus.

First, activities aimed at rural and IDP communities alone are not sufficient to ensure that all potential conflict participants are included into a peace process. Considering the heterogeneity of the conflict, the diversity of its participants and its geographical scope, peace-building programmes may need to focus on those segments of the population which are most likely to be involved in conflict. Programmes working with young people need to ensure that their target groups are not only well aware of the importance of non-violence, which is mostly the type of work that the current peace-builders are engaged in, but, most importantly, that young people are free in expressing their beliefs, points of view and are safe from persecution. The number of young people joining the insurgents can be reduced by increasing the social and physical security of the new generation and ensuring the preservation of their identity as ethnic and religious minorities within the Russian Federation. This implies that community grass-roots level peace-building remains a priority, but its scope and target groups need to be expanded to include youth in urban and rural areas, working and middle classes alike.

Second, peace-building should be multilateral, i.e. peace-builders have to work with both local and federal authorities as well as with the insurgents. Obviously, it would be impossible to convince the insurgents to lay down their weapons as long as there are no guarantees for their security in the short term and no improvements in the areas of social and economic security in the long term. On the other hand, it is unlikely that law enforcement will change its strategies as long as the threat from insurgency persists. Therefore, the job of peace-builders in that area might be that of mediators having an ability to reach out to rebel field commanders and law enforcement officials at local and federal level and ensuring that both sides respect any terms of peace which are set. This task requires civic groups to be influential enough in order to decentralize state institutions and ensure the transparency of their service.

The peace process, necessary to ensure the efficacy of humanitarian and development efforts in the region, has to originate from below in order to succeed in the North Caucasus. However, the bottom-up peace-building approach suggested above is a means of conflict resolution which can only succeed if implemented by non-state actors, that is civic groups, represented by both local and international NGOs.

Author:

Huseyn Aliyev holds a bachelor’s degree in European Studies from Azerbaijan State University of Languages, Baku, and a master’s degree in International Politics from Kyung Hee University, South Korea. He is currently in his last year of the graduate programme in Humanitarian Action at Ruhr-Universität, Bochum, Germany. His current research interests are civil society in the North Caucasus and Russia, conflict in the North Caucasus and democratization in the Caucasus.

Source:

This article was published by CRIA (Caucasian Review of International Affairs) in its Vol 4.4 Autumn (http://cria-online.org/13_2.html) online journal pages 325-341. (PDF)

Notes:

1 Human Rights Watch, “World Report 2010: Events of 2009,” 2010, www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/wr2010.pdf (accessed October 12, 2010).

2 International Crisis Group, Crisis Watch, April 1, 2010, No 80, http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/publication-type/crisiswatch/2010/crisiswatch-80.aspx (accessed October 12, 2010).

3 Andrew McGregor, “Military Jama’ats in the North Caucasus: A Continuing Threat,” Jamestown Foundation, (2006), 2.

4 Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), “Violence in the North Caucasus: Trends since 2004,” Human Rights and Security Initiative (2008).

5 Sergei Davydov, “The Caucasus Emirate on the road from Yemen to Algeria (Part 1),” Prague Watchdog, (June 6, 2009).

6 Chechenpress, “Statement by the Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria,” (October 31, 2007).

7 Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), “Violence in the North Caucasus, 2009: A Bloody Year,” Human Rights and Security Initiative, 2009.

8 BBC News, “Russia ends Chechnya operation,” April 16, 2009.

9 Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), “Violence in the North Caucasus: Summer 2010: Not Just a Chechen Conflict,” Human Rights and Security Initiative (2010).

10 Medvedev speaking on a live broadcast on three Russian TV channels on December 24, 2009.

11 Ibid.

12 John Paul Lederach, Building peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies (Washington D.C.: United States Institute of Peace, 1997), 40.

13 Ibid., 42.

14 International Crisis Group, “Russia’s Dagestan: Conflict Causes,” Europe Report No 192 (June 3, 2008), 8.

15 Roland Dannreuther, “Islamic radicalization in Russia: an assessment,” International Affairs, vol. 86:1 (2010): 109-126.

16 Maciej Falkowski and Mariusz Marszewski, “The “Tribal Areas” of the Caucasus: The North Caucasus – an enclave of “alien civilization” within the Russian Federation,” OSW Studies, Warsaw, April 2010, 63.

17 John Paul Lederach, Building peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies (Washington D.C.: United States Institute of Peace, 1997), 43.

18 Johan Galtung, Peace and Peaceful Means: Peace and Conflict, Development and Civilization (London: Sage, 1996).

19 John Paul Lederach, Building peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies (Washington D.C.: United States Institute of Peace, 1997), 52.

20 John Paul Lederach in Building peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies (Washington D.C.: United States Institute of Peace, 1997) and Adam Curle in New Challenges for Citizen Peacemaking, “Medicine and War,” vol. 10:2 (1994): 96-105.

21 Mary B. Anderson & Lara Olson, “Confronting War: Critical Lessons for Peace Practitioners,” The Collaborative for Development Action, Inc. (2003), 25.

22 Thania Paffenholz & Christoph Spurk, “Civil Society, Civic Engagement and Peace Building,” Social Development Papers, Paper No. 26, Social Development Department, The World Bank (2006).

23 Camilla Orjuela, “Civil Society in Civil War, Peace Work and Identity Politics in Sri Lanka,” PhD Dissertation, Department of Peace and Development Research, University of Göteborg, 2004.

24 Thania Paffenholz & Christoph Spurk, “Civil Society, Civic Engagement and Peace Building,” Social Development Papers, Paper No. 26, Social Development Department, The World Bank, 2006.

25 Mary B. Anderson & Lara Olson, “Confronting War: Critical Lessons for Peace Practitioners,” The Collaborative for Development Action, Inc. (2003), 25.

26 Ashutosh Varshney, “Ethnic Conflict and Civil Society: India and Beyond,” World Politics 53 (April 2001), 362–98.

27 Aileen Toohey, “Social Capital, Civil Society and Peace: Reflections on Conflict Transformation in the Philippines,” Australian Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, University of Queensland, Australia (2005), 17.

28 Ibid.

29 Juliana Ramirez, “Rethinking the Link between Civil Society and Civil War: the Case of Colombia” (Armed Groups Project, Working Paper, 2008).

30 Stanislav Kalyvas, The Logic of Violence in Civil War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

31 Pat Johnson, “The Puntland Experience: A Bottom-up Approach to Peace and State Building,” Interpeace, PDRC (2008).

32 Kristian Harpviken and Kjell Kjellman, “Beyond Blueprints: Civil Society and Peacebuilding” (Concept Paper, International Peace Research Institute: Oslo, August 9, 2004).

33 Béatrice Pouligny, “Civil Society and Post-Conflict Peace Building: Ambiguities of International Programs Aimed at Building ‘New Societies’,” paper presented to the Conference Post-conflict peace building: How to gain sustainable peace? Lessons learnt and future challenges, held at the Graduate Institute of International Studies, Geneva, October11–14, 2004.

34 Soldiers’ Mothers NGO Website, http://www.soldiers-mothers-rus.ru/history.html (accessed July 15, 2010).

35 FEWER International, Partners in Eurasia, http://www.fewer-international.org/pages/eurasia/partners_in_eurasia_33.html (accessed July 15, 2010).

36 Peacemaking Mission of General Lebed, http://www.rozysk.org/i/about_pmgl (accessed July 15, 2010).

37 Ibid.

38 Mairbek Vatchagayev, “North Caucasus Insurgency Attracting Mainly Young and Committed Members,” North Caucasus Analysis, vol. 10:2 (January 15, 2009).

39 According to the Chief Commander of North Caucasus Military District, Gen. Nikolai Sivak: “local population either supports armed groups or treats them neutrally, does not resist them and does not report them to federal authorities. If not for the support of locals, armed groups would have long been eliminated.” (In an interview to НЕЗАВИСИМАЯ [Independent] newspaper on April 27, 2009.)

40 “We created and systematized internal support techniques, and Sharia gives us clear rules for collecting military zakat (taxes). We prepared regulations and orders, which were distributed on our territories by our naibs (deputy commanders). In today’s situation, financial or any other types of support are no longer voluntary actions but fard ‘ain (compulsory) for every true Muslim because we are in war. We do not take anything that is above a fixed percentage rate, we do not rob poor families or those who suffered from the regime; instead, we support them as much as we can afford.” Leader of Yarmuk jamaat, operating in Kabardino-Balkaria, in an exclusive interview to North Caucasus Analysis, vol. 10:11 (March 20, 2009).

41 Mairbek Vatchagayev, “North Caucasus Insurgency Attracting Mainly Young and Committed Members,” North Caucasus Analysis, vol. 10:2 (January 15, 2009).

42 Jamestown Foundation, “Russia Adds Poison to its Counter-Insurgency Arsenal in the North Caucasus,” North Caucasus Weekly, vol. 11:3 (2010).

43 Amnesty International, “Russian Federation: Rule without Law: Human Rights violations in the North Caucasus,” London (July 2009).

44 Nonviolence International, “About Us,” http://nonviolenceinternational.net/?page_id=2 (accessed July 27, 2010).

45 Nonviolence International, “Projects,” http://www.policy.hu/kamenshikov/ninis/russian.html (accessed July 20, 2010).

46 Ibid.

47 North Caucasus regional Peacebuilding program of civil organizations based on Sub-regional Peacebuilding Action Agenda of North Caucasus NGO’s,

http://www.igpi.ru/monitoring/north_caucas/1126863891.html (accessed July 20, 2010).

48Non-Violence International, Report: Операционно-Методическое Сопровождение Реализации Комплексных Миротворческих Программ [Operational and Methodological Implementation of Multi-Sector Peace-building Programmes], http://www.policy.hu/kamenshikov/ninis/russian.html (accessed August 20, 2010).

49 Institute for Humanities and Political Studies, http://www.igpi.ru (accessed July 20, 2010).

50 Peacebuilding UK, “About,” http://peacebuildinguk.org/home (accessed August 20, 2010).

51 Peacebuilding UK, “Peacebuilding,” http://peacebuildinguk.org/about/peacebuilding (accessed August 20, 2010).

52 Peacebuilding UK, “Community Development,” at http://peacebuildinguk.org/about/community-development (accessed August 20, 2010).

53 FEWER International, “Dialog,”

http://www.fewer-international.org/pages/eurasia/dialogue_29.html, (accessed August 20, 2010).

54 Open Society Foundation, OSI Grantee Intercentre Launches “Cross-Cultural Understanding and Peace in North Caucasus” Project, http://www.soros.org/initiatives/esp/news/intercentre_20080903, (accessed 20.08.2010).

55 Valery Dzutsev, “Russia’s Government-Sponsored Expert Community Reaches out to North Caucasus,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, vol. 7:75, September 10, 2010, http://www.jamestown.org/programs/ncw/single/?tx_ttnews[tt_news]=36824&cHash=b3b684c475 (accessed November 7, 2010).

56 Dmitry Florin & Enver Kisriev, “Project ‘Peace to the Caucasus’ may draw officials’ attention to regional problems,” Caucasian Knot, April 2010.

57 Dmitry Solovyov, “Russia’s Dagestan Head to Pardon Repentant Rebels,” Reuters, February 20, 2010.

58 The International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights (IHF), “Amnestied People as Targets for Persecution in Chechnya,” Vienna, May 16, 2007.

I am so delighted to read the article, since I am a traditionalist believe on bottom up approach, to update indigenous institution with modern scientific knowledge, against the donor approach on top down. As they considered themselves the expert with out knowing the ground realities, custom and traditions and impose what they think are right as compared to what community want. The result in most of the cases is what we saw is zero due to lack of ownership.

On the other hand I am not convinced by the author arguments /definition of civil societies referred to NGO only. If we really want a Bottom up approach then we must consider the gross root Indigenous organization as they have decisive role in peace building. Like Jirga in Pakistan-Afghanistan, Punchayat in India-Pakistan, Coming to the carpet in Armenia, Majlis in Iran, Sulha in Middle East, Gachacha, Padre, in Africa, Badung in Philippine, soviet in Russia. Similarly there must be indigenous organization in caucus, but I did not saw any reference to that in the whole article. Such indigenous organizations provide bases to conflict or peace efforts in the bottom up approach. If in the caucus they are present what are its role, if not present why. How NGO involve them in there peace building bottom up approach, is there any research on that to be shared with the Donor are few areas to be explore further.