US-Turkish Trade Relations – Analysis

By CRS

By Shayerah Ilias Akhtar*

Turkey, a NATO ally and emerging market straddling Europe and the Middle East, offers potential for U.S. trade and investment. U.S.-Turkish trade ties are relatively weak overall, and their further expansion depends on a number of economic and political factors. At a time of continued bilateral tension, Congress is monitoring U.S.-Turkish trade ties and related policy developments more intensively, as well as considering possible sanctions against Turkey.

Turkey’s Economy

At $767 billion in gross domestic product (GDP, current dollars), Turkey was the world’s 19th largest economy in 2018. After a financial crisis in the early 2000s, Turkey’s economy largely rebounded, due to Turkish government actions to make market-oriented reforms, improve rule of law in commercial markets, and invest in infrastructure. EU membership prospects also helped drive economic reforms, but Turkey’s EU bid is stalled currently. Despite economic growth, Turkey continues to face challenges, including sizeable debt denominated in foreign currencies and high inflation.

In late 2018, a currency crisis in Turkey eroded investor confidence. Economic growth subsequently slowed, and the Turkish government is engaged in expansionary policies to boost the economy. Downside risks to the Turkish economy remain, including domestic political uncertainty and foreign policy tensions.

Turkey has reduced its trade barriers since 1995, following its accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) and conclusion of a Customs Union with the EU, which allows free movement of goods between Turkey and the EU (excluding agriculture, coal, and steel). Turkey has a well- diversified export base, but relies heavily on energy imports. Turkish firms are typically toward the end of global supply chains, manufacturing most end-use products of high-value and sourcing intermediate inputs elsewhere. One exception is the Turkish auto industry, which supplies components to major global auto manufacturers. Turkey also recently unveiled prototypes of what it hopes will be its first domestically-produced electric car.

Bilateral Trade and Investment Ties

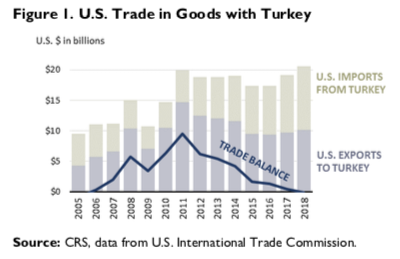

Goods. Turkey is a small but growing U.S. trading partner (see Figure 1). In 2018, two-way goods trade accounted for less than 1% of U.S. global trade in goods. The United States exported $10.2 billion in goods to Turkey (led by civilian aircraft, engines, and parts; waste and scrap; cotton; coal; and petroleum refinery products), and imported $10.3 billion in goods from Turkey (led by iron and steel products; carpets and rugs; autos and other light-duty motor vehicles; petroleum refinery products; and stone products).

The trading relationship is more consequential for Turkey. The United States was both its fourth largest market for exports (5.5% share) and imports (5.1%). The EU, overall, is Turkey’s leading trading partner, representing 47.8% of its exports and 36.4% of its imports. (WTO, 2017 data.)

Services. In 2018, bilateral services trade ($5 billion) was about a quarter of bilateral goods trade. U.S. services exports were $3.1 billion and imports were $1.8 billion, resulting in a trade surplus of over $1 billion. Travel (e.g., for education or business), transport, and business services were top traded services. Charges for Turkish use of U.S. intellectual property rights (IPR) was a top U.S. export.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). While Turkey accounts for less than 0.1% of the stock of U.S. FDI abroad and FDI in the United States, bilateral investment ties are notable in some respects. U.S. majority-owned multinational firms in Turkey had 55,000 employees in 2017, and, for some U.S. companies, Turkey serves as a regional base for doing business. Turkey was the 9th-fastest-growing source of U.S. inbound FDI in 2018. According to official Turkish data, between 2003 and 2018, the United States cumulatively comprised 8.8% of Turkey’s inbound FDI. The EU, at a share of 68.6%, ranked as Turkey’s largest source of FDI.

Key Trade Issues

Tariffs. On October 14, 2019, after Turkey’s incursion into northeast Syria, President Trump announced plans to apply sanctions against Turkey and raise “Section 232” national- security-based tariffs on U.S. steel imports from Turkey from 25% back to 50%. While the Administration applied the sanctions and then lifted them after an announced cease- fire in hostilities, it has not applied the tariff increase.

Section 232 steel tariffs on Turkey, when first applied in March 2018, were 25%, in line with other countries subject to the tariff measure. In August 2018, the President doubled steel tariffs to 50% for Turkey, on the basis that U.S. steel imports had not declined as much as expected and U.S. domestic steel capacity use had not risen to the target level. Some analysts argued, however, that the new steel tariffs appeared to be at least partly linked to Turkey’s prosecution of a U.S. pastor whose release President Trump had demanded; the pastor was released in October 2018. In May 2019, the President lowered the steel tariffs on Turkey to 25%, citing the decline in U.S. steel imports from Turkey and improved U.S. industry capacity utilization.

In 2018, Turkey was the 12th-largest supplier of U.S. steel imports under the Section 232 tariffs, accounting for $774.7 million (or 2.6%) of the relevant U.S. steel imports. This represented a decline of 35.1% compared to 2017. The United States historically has been a top destination for Turkish steel exports. Turkey is shifting its steel exports more to other markets, such as in Europe.

Turkey has retaliated against the U.S. tariff measures. In June 2018, Turkey applied tariffs ranging from 5% to 40% on $1.8 billion of imports from the United States (e.g., foodstuffs, paper, plastic, structural steel, machinery, and vehicles). Following the doubling of the steel tariffs in August 2018, Turkey adjusted tariffs on the U.S. imports it originally targeted to rates ranging from 4% to 140%. After the U.S. tariff reduction on Turkish steel, Turkey revised its retaliatory tariffs to rates ranging from 4% to 70%.

The tariff measures are subject to challenges in the WTO. Turkey joined the EU’s complaint against the U.S. Section 232 measures, and also launched its own complaint in August 2018 against the U.S. doubling of tariffs on steel and aluminum imports from Turkey. (The doubling of aluminum tariffs, which President Trump announced at the same time as he announced the doubling of the steel tariffs, has not been applied.) The United States is challenging the retaliatory actions of Turkey, the EU, and other trading partners in the WTO. Separately, the U.S. Court of International Trade is allowing a challenge by a U.S. steel importer against the U.S. government for August 2018 action to double the Section 232 tariffs against Turkey.

Other Trade Barriers. The United States is a generally open market; by value, 79.3% of Turkish agricultural exports and 68.7% of Turkish non-agricultural exports entered the United States duty-free in 2017. U.S. firms, meanwhile face challenges doing business in Turkey. Issues cited by the U.S. Trade Representative include Turkey’s:

- bureaucracy and weakening rule of law;

- “forced” localization barriers to trade, such as requiring storage of Turkish citizens’ personal data within Turkey;

- high average agricultural tariffs (41.8%, versus 5.3% by the United States) and hikes on tariffs in multiple sectors, which are within WTO limits (high “bound” rates) but increase uncertainty for U.S. exporters; and

- inadequate IPR regime, including Turkey’s role as a source of and transshipment point for counterfeit goods.

Generalized System of Preferences (GSP). Effective May 2019, the Trump Administration ended Turkey’s eligibility for GSP, a U.S. trade and development program that grants non-reciprocal, duty-free treatment to certain U.S. imports from developing countries that meet eligibility criteria.

The President cited Turkey’s increased level of economic development, a GSP criterion, as the reason for ending Turkey’s eligibility, pointing to Turkey’s rise in gross national income per capita, declining poverty rates, and greater export diversification. In 2018, U.S. GSP imports from Turkey (e.g., jewelry, stones, and motor vehicle parts) were 18% of all U.S. imports from Turkey. While Turkey was GSP’s fifth-largest user in 2018, the amount of Turkish-U.S. trade under GSP ($1.9 billion) was a small share of Turkey’s world exports ($168 billion).

Turkish-EU Customs Union. Under the Customs Union, Turkey is bound to the EU’s common external tariff with “third countries.” As a result, Turkey must open its market to countries with which the EU has trade agreements, on terms negotiated by the EU; yet, Turkey does not have any guarantee that these countries will grant Turkey reciprocal access to their markets. This potential imbalance is of growing significance for Turkey as the EU negotiates trade agreements with larger countries. Turkey and the EU have expressed interest in renegotiating the Customs Union, but Turkey’s political situation make the prospects uncertain.

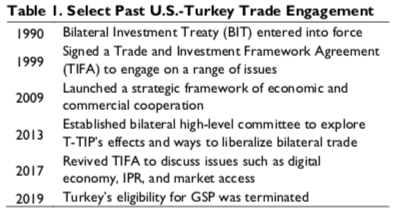

Turkish-U.S. Trade Negotiations. During the Obama Administration, Turkey sought to negotiate a free trade agreement (FTA) with the United States, prompted by concerns about the impact of the proposed U.S.-EU Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP). Instead, the United States and Turkey engaged in other ways to address concerns (Table 1). Under the Trump Administration, the T-TIP negotiations ceased, but new U.S.-EU trade negotiations, depending on their progress, could renew Turkey’s interest in a bilateral FTA.

Meanwhile, the Administration has expressed interest in a deal to grow U.S.-Turkish trade to $100 billion, four times the 2018 level of trade. Prospects for a deal may be tied to improvement in bilateral relations on other issues. In October 2019, at the same time that he announced the planned increase of the steel tariffs back to 50%, President Trump also announced an immediate stop to trade talks. In November 2019, President Trump raised with President Erdogan the idea of reopening trade talks under certain conditions, eliciting mixed responses within Congress.

Selected Issues for Congress

- What are the benefits and costs of addressing U.S.- Turkey differences through continued tariff escalations or a bilaterally negotiated resolution, or in the WTO?

- What are options for the United States and Turkey to grow their bilateral trade? Is such a focus desirable?

- What are the implications of using tariffs as a sanction against Turkey for bilateral ties and U.S. trade policy?

*About the author: Shayerah Ilias Akhtar, Specialist in International Trade and Finance

Source: This article was published by Congressional Research Service (PDF)