Pakistan: Ahmadis Killed, Tortured, Hounded – Analysis

By SATP

By Sanchita Bhattacharya*

On May 17, 2022, Abdul Salam, a 33-year-old man from the Ahmadi community was stabbed to death by a seminary student, Hafiz Ali Raza alias Mulazim Husain, in the Okara District of Punjab.

The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), condemning the killing, tweeted, “The brutal murder of an Ahmadi man in Okara, who was reportedly stabbed to death by a seminary student, serves to remind us just how precarious the lives of religious minorities have become. Until the rising tide of religiosity is stemmed and better protection mechanisms put in place, they will remain lesser citizens. This is unacceptable and the perpetrators must be brought to book.”

Earlier, on March 5, 2022, a man was killed and another wounded when unidentified assailants attacked the clinic of an Ahmadi doctor in the Scheme Chowk area of Peshawar, the provincial capital of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). A Police official disclosed that the doctor was not at the clinic when the attack took place.

As reported on February 7, 2022, the Punjab Police defaced as many as 45 Ahmadi graves in the Hafizabad District of Punjab, removing plaques and destroying gravestones at the cemetery.

On November 9, 2021, a 40-year-old Ahmadi man, identified as Kamran Ahmad, was shot dead by unknown assailants in Peshawar.

On September 3, 2021, a 55-year-old Ahmadi man, Maqsood Ahmed, was shot dead by unidentified assailants at Dharowal in the Gujrat District of Punjab.

According to partial data collated by SATP, since March 6, 2000, when SATP started compiling data on conflicts in Pakistan, at least 129 Ahmadis have been killed and 139 injured in 33 incidents of violence.

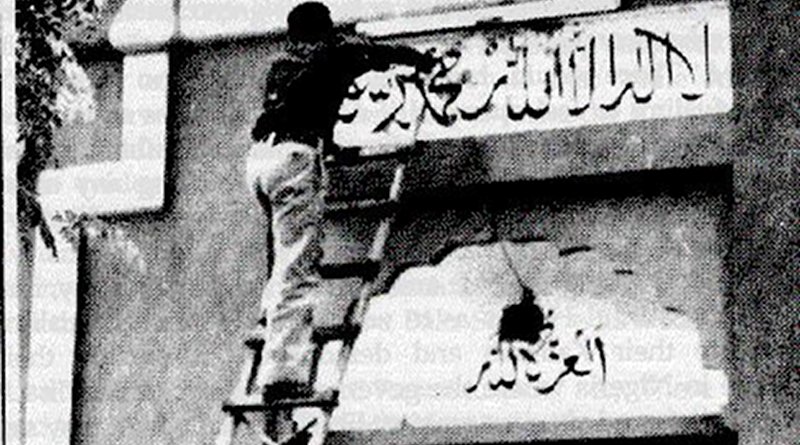

A report titled “Violence and Discrimination against Women of Religious Minority Backgrounds in Pakistan”, published by the Institute of Development Studies in November 2020, states that, in Pakistan, between 1984 to 2019, 265 Ahmadis were killed; 393 were assaulted for their faith; there were 70 instances of Ahmadis denied burial in a common cemetery; 39 Ahmadi bodies were exhumed; and there were 44 incidents of removing Kalima (the formal content of the declaration of the Islamic faith) from Ahmadi homes and shops, and on 103 occasions Kalima were removed from Ahmadi mosques. Data on Police cases registered against Ahmadis on religious grounds indicates that 765 Ahmadis were booked for displaying the Kalima, 38 were arrested for making the Islamic call to prayer (azaan), 453 were arrested for ‘posing’ as Muslims, 161 were booked for using Islamic epithets, 93 were charged for performing namaaz (a mandatory prayer which Muslims offer five times a day), 825 were booked for preaching, 49 were booked for allegedly defiling the Holy Qur’an, 1,222 Ahmadis were charged in other religious cases, and 315 Ahmadis were charged under the blasphemy law.

According to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan(HRCP), three Ahmadis were killed in 2020. During the year at least 24 cases were registered against Ahmadis on religious grounds, including a jeweler who was booked in Toba Tek Singh for having sacrificed a cow and distributed the meat among Sunni Muslims. In 2021, three Ahmadi community members were killed and nine were assaulted. Over 100 cases were registered against members of the community on religious grounds, including ‘posing as Muslims,’ preaching their faith, and alleged blasphemy.

Meanwhile, the Violence Register PK’s Violence Report 2021 data shows that, between 1963 and 2021, a total of 231 incidents targeting Ahmadis have taken place, resulting in 177 deaths and 193 injured. The report notes: “Punjab proves to be the most dangerous province for the Ahmadiyya community with 76% of the recorded faith-based attacks. Lahore saw the highest number of casualties with 47% of the total casualties recorded.”

Ahmadis are considered by mainstream Pakistani Muslims as heretics because of their belief in the prophethood of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the founder of the Ahmadi sect. In 1984, the then Pakistan President General Zia ul Haq promulgated Ordinance XX introducing Ahmadi-specific laws to prohibit Ahmadi people from engaging in “anti-Islamic activities,” restricting them from referring to themselves as Muslims or preaching their belief. Ordinance XX prohibits Ahmadis from self-declaration as a Muslim, to make prayer call (azaan), from paying alms (zakaat), from observing fast during Ramzaan and pilgrimage to Mecca. All such acts also fall under Blasphemy laws for outraging the feelings of Muslims, punishable under PPC 298C with three years imprisonment and a fine, and under PPC 295C with death. The Ahmadi population in Pakistan has declined over almost two decades, according to the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics report on the sixth Population and Housing Census-2017, with Ahmadi/Qadiani people making up just 0.09 per cent of Pakistan’s population of 207.68 million However, the 1998 census indicated that they constituted 0.22 per cent of the population, according to the Refworld report, Pakistan: Situation of members of the Lahori Ahmadiyya Movement in Pakistan; whether differences exist between the treatment of Lahori Ahmadis and Qadiani Ahmadis; procedure for verification of membership in Lahori Ahmadiyya Movement, February 2006, published on March 1, 2006.

The main population centres for Ahmadis in Pakistan are Sialkot, Multan, Rawalpindi, Lahore and Faisalabad in Punjab; Quetta in Balochistan; and Karachi in Sindh. They are also in significant numbers in Sargoda, Khewra, Shahpur, Bhalwal, Shahpur and Gujranwala. Rabwa or Chenab Nagar in Punjab is still considered the centre of the Ahmadi community. Unfortunately, most Ahmadis in Pakistan live shadowy and restricted lives. Many never reveal themselves to people outside the community. Every Ahmadi, knows someone chased out of university or work or the country after being outed. In Pakistan, Ahmadis aren’t employed in government departments or the Police, nor can they hold office unless they contest as religious minorities. Every year, the community braces itself for processions led by orthodox Muslim clerics, who rattle through towns and cities throwing threats and insults at Ahmadis, declaring them wajib-ul-qatl — worthy of being murdered. Despite being less than 0.09 per cent of Pakistan’s total population, Ahmadis constitute almost 33 per cent of persons against whom blasphemy cases are registered.

Even in cyberspace the Ahmadis are not safe. While anti-Ahmadi speech proliferates on the internet, the Pakistani state cracks down on Ahmadi content online. Under the 2016 Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act (PECA), authorities can review internet traffic and report ‘blasphemous’ or offensive content to the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) for possible removal, or to the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) for possible criminal prosecution. In 2020, the PTA issued new rules mandating data localization. Under these new regulations, tech platforms face a fine of up to USD 3.14 million for failure to curb the sharing of content that may be religiously offensive, sexually explicit, or a threat to national security. In December 2020, shortly after the passage of these rules, PTA sent a legal notice to the US-based administrators of trueislam.com, which provides general information about Ahmadi beliefs. The PTA claimed that the site was in violation of Pakistan’s Constitution, a move condemned by Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and other rights groups. The website is still up, but remains blocked in Pakistan.

Minorities in Pakistan are more persecuted than protected. Pakistani authorities have not only failed to protect Ahmadi Muslims, but also facilitated their harassment and intimidation. The authorities are often complicit in the destruction of Ahmadi houses of worship and tombstones that if they reflect the Muslim belief. Continuous fear of being targeted or accused of blasphemy has caused many Ahmadis of Pakistan to flee to countries such as Sri Lanka, Nepal, Indonesia, and Malaysia, but, unfortunately, they often face further discrimination in these countries as well.

*Sanchita Bhattacharya

Research Fellow, Institute for Conflict Management