Pie In The Sky: The Artificial Ace – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

A spectacular dogfight scoreline is tantalizing, but still leaves a lot unsaid about the future of Artificial Intelligence and autonomous warfare.

By Angad Singh

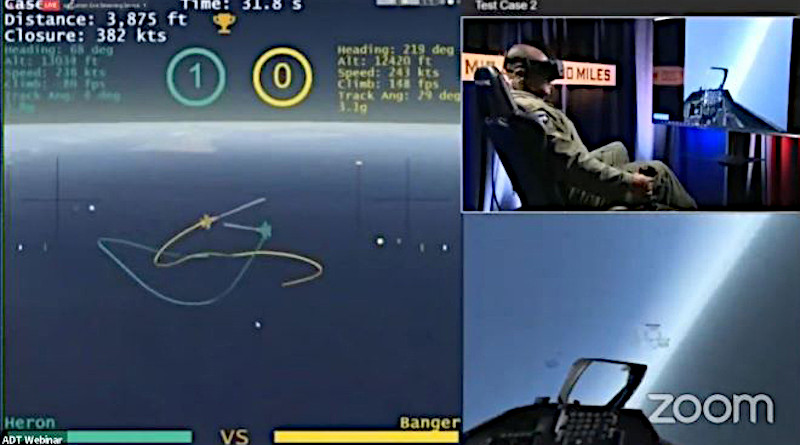

In a highly publicised match up on 20 August, an artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm beat a seasoned human aviator in a series of simulated dogfights. The bout took place entirely in software, with the USAF F-16 pilot (known only by his call sign, ‘Banger’) flying with the aid of a virtual reality setup against an all-computer AI opposition from Heron Systems, a small US-based defence contractor.

The rules limited the combatants to five rounds of within visual range combat, with guns being the only weapons available. Banger, a graduate of the elite USAF Weapons School, lost all five engagements. This simulation, called ‘AlphaDogfight,’ was the final phase of an autonomous technology initiative that is a subset of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Air Combat Evolution (ACE) programme, which aims to bring AI and machine learning to bear on critical elements of future aerial combat.

The DARPA commentators for the global livestream made some effort to contextualise the results of the day, noting that the AI had perfect awareness in the simulation, something that would not be possible in the real world, and that certain tactics were simply not realistic in actual combat, such as the head-on, close-in gun firing that netted the Heron artificial agent most of its victories. Even though he called it “a giant leap” for autonomous air combat technology, one of the commentators, himself an F-16 pilot, pointed out that the successful demonstration was nonetheless “a far cry from going out in an F-16 and flying actual BFM [Basic Fighter Manoeuvres].”

The DARPA commentary also made clear that while the display of simulated autonomous combat was a significant milestone accomplished in record time, it was only a first step toward the larger goals of the ACE programme. Autonomous combat simulations will first have to demonstrate greater robustness and handle more complex scenarios in software, before eventually moving to sub-scale aircraft demonstrations in the real world, and much later being tested on actual combat-representative platforms.

Technical quibbles and caveats aside, the singularly impressive demonstration does drive home the changes imminent in the nature of warfare, and not just in the aerial domain. Beyond the dangers of combat and the physical limitations of the human body that autonomous technologies mitigate or eliminate, AI in warfare, even just at the tactical level, has distinct advantages — algorithms learn faster than humans, their ability to parse data is not subject to fatigue or bias (barring what is programmed in — a topic that does merit further exploration), and their outputs are more precise.

A lot of this is already in use today, for example in sensor fusion across multiple sensors, or multi-platform, multi-sensor data fusion to dramatically enhance battlespace awareness, whether for fighter pilots, fleets at sea, or air defence commanders in the tactical battle area. Programmes like DARPA’s ACE simply aim to take this to the next logical level — extending beyond decision support to actual autonomous decision making.

AI and autonomous technologies have come a long way. Far from being esoteric concepts aimed at distant horizons, autonomy in the air and on the surface are a reality today, with drones operating without human intervention from aircraft carriers, tankers delivering fuel to fighters, and ships traversing vast distances unaided. In fact, the speed with which the AlphaDogfight demonstration itself was conducted is indicative of the maturity of the field — in just 12 months, eight companies delivered credible autonomous performances, and the leading solution among them managed to handily beat a human pilot.

The ACE programme is air-focused, intending to team pilots in manned aircraft with swarms of highly capable autonomous drones able to dogfight, strike, jam or simply observe an adversary. The basic concept however — transforming the pilot who was once a vehicle or weapon operator, who is now a systems operator, into a ‘situation manager’ focused on tasking and delegation in the battle space — applies to combat on land and sea as much as the aerial domain. It is no surprise then, that major military powers, including China, are investing heavily in military AI.

Meanwhile, questions regarding the ethics of autonomous weapons have become more pressing in face of ever accelerating research, with calls for outright bans on fielding or further development. China has hedged by calling for a ban on the use of such weapons, but not their development, while the broader international community is yet to arrive at a consensus. As with missiles or nuclear technology in the past, there is a danger that India might be frozen out of the AI game before it even has a chance to start.

As India faces the undeniable, inevitable trimming of its manpower intensive, fiscally constrained military, autonomous ‘force multipliers’ will logically come to the fore. India’s defence bureaucracy, known for indecision, and its defence practitioners, prone to parochialism, must recognise that the Indian military’s chronically delayed modernisation could benefit greatly by skipping a generation straight to widespread adoption of autonomous platforms, whether operating in teams with human warfighters or completely autonomously. For instance, the Indian Navy’s dangerous lack of minesweepers could be remedied with rapidly produced autonomous mine countermeasures vessels instead of far larger and more expensive manned ships. Persistent surveillance, something chronically lacking across the three services, and most recently exposed by the crisis in Ladakh, is easily addressed by autonomous platforms. And of course, the IAF’s oft-lamented fighter fleet would be able to dramatically increase deliverable effects if recapitalisation involved light, optionally expendable autonomous swarms rather than full fledged manned fighters that are orders of magnitude more expensive.