Shaping The Idea Of India – Analysis

It was the constitution of India, adopted on January 26, 1950, which defined modern India – a democratic State with equal rights for all secured by affirmative action.

It was on January 26, 1950, known as “Republic Day”, that free India defined itself as a modern, equalitarian and non-discriminatory democracy with one-man-one vote across its diverse population. The Indian constitution, which was adopted on that day, made explicit provisions for the realization of these ideals.

Although “democratic” constitutions had been adopted elsewhere too, the Indian constitution is unique in one way: it was democratic and equalitarian from the word go. While it took the older Western democracies centuries to extend rights to all (franchise was limited, women could not vote, and in the US, Blacks lacked full civil rights till the mid-1960s) the Indian constitution conferred democratic rights across the board and at once. And to realize them, it inaugurated an era of affirmative action to rid the country of primordial social and economic inequalities.

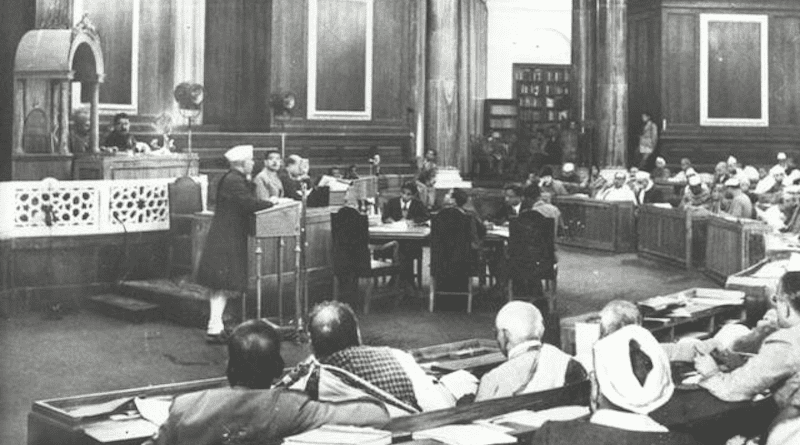

The “idea of India” or “the idea of modern India” to be precise, was conceived collectively in the Constituent Assembly (CA) through intense debates. The members of the CA were elected from all parts of the country and were led by an exceptionally gifted body of men like Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad.

The Congress party had been toying with the idea of a constitution for an independent India from the early 1930s. But it was when the British indicated that they were leaving in 1946, that it became a reality. A 389-member Constituent Assembly (CA) was set up by the government with 292 elected indirectly by the Provincial Assemblies that had come into being following the 1946 Provincial elections. The CA also included 92 members from the Princely States. Most members were from the Congress party after the Muslim League left in quest of Pakistan.

However, the Congress at that time was an umbrella organization containing rightists, leftists, Hindu nationalists, Muslims, spokesmen for the propertied classes and those of the workers.

The CA deliberated over 165 days, from December 1946 to December 1949. The CA also went beyond the House and entertained suggestions from the public. The proceedings of the CA, published in 11 volumes, are a “treasure trove invaluable to the historian” says Ramachandra Guha in a detailed account of CA debates in his book “India After Gandhi” (MacMillan 2007).

Guha points out that the years 1946 to 1949 were marked by unprecedented turmoil because of food shortages, communal rioting, the refugee influx and the first India-Pakistan war over Kashmir. This made the task of drafting a consensus-based constitution very difficult indeed. However, amidst calls to draft a constitution on the basis of ancient Hindu thought, Nehru firmly stated that it will have “adequate safeguards” for the minorities and the Depressed and Backward classes. It will be based on the “great past of India” as well as the thoughts of Gandhi and the ideas behind the French, American and Russian revolutions, he added.

According to Guha, while the basic ideological framework was given by Nehru, Vallabhbhai Patel, being a quintessential committee man and negotiator, moved the clauses through the committees. But the actual drafting of the constitution was left to the Drafting Committee chaired by Dr.B.R.Ambedkar, a lawyer and leader of the Harijans, the most backward Indian community. Ambedkar pressed hard for affirmative action in favor of the Harijans because he believed that “Democracy in India is only a top dressing on an Indian soil which is essentially undemocratic.”

The constitution had provision for justiciable Fundamental Rights which included the right to practice any religion and the right not to be discriminated against on the basis of caste or religion. Untouchability and forced labor were banned.

However, the predominance of Western concepts and the adoption of the basic unitary structure of the pre-independence Government of India Act of 1935 irked some members. Gandhian Mahavir Tyagi saw nothing “Gandhian” in the constitution. But the leaders and drafting committee members were trying to fashion a constitution that would be able to face the challenges posed by modern political, social, economic forces.

There were intense debates on whether the State should be federal or unitary. Under the 1935 Act, India was a unitary State though there were provinces with elected Legislatures. The framers of the constitution pitched for a strong Centre keeping most of the powers and high-yielding revenue sources. They argued that centralization is needed to curb separatist forces and ensure equitable development of the diverse country. At that time, India had seen separation in the form of Pakistan. Additionally, 500-odd theoretically independent Princely States had to be brought under the Indian Union.

But the high degree of centralization envisaged worried many members who feared that the provinces might become mere vassals of the Center.

However, the Drafting Committee would not yield. According to Guha, Dr.Ambedkar even said that the constitution should be more centralized than the 1935 Act. Minorities also wanted a centralized State because, in their view, Provincial governments had a tendency to pander to local passions. The minorities reposed faith only in the secularism of national leaders Gandhi and Nehru.

Some Muslim members from Madras asked for Separate Electorates for Muslims as was the case under British rule. Under the Separate Electorates system, Muslims elected only Muslims for a specified list of seats. But this was an explosive issue because Separate Electorates had increased the gulf between Muslims and Hindus and led to the creation of an independent Pakistan. Home Minister Valabhbhai Patel bluntly said that those demanding separate electorates could go to Pakistan as it had been created for such people.

However, virtually all were in favor of reservations in legislatures and government jobs for the Tribals and Harijans. Harijan was the term used by Gandhi for the so-called Untouchables, who had been on the margins of Hindu society for close to 5000 years. Some like Gandhian Mahavir Tyagi warned that the reserved jobs would go only to a thin “creamy layer” of the Harijan community and suggested reservations on the basis of class and not caste. But Tyagi’s idea had no takers.

The most hotly debated subject was the official language of India. Should it be English or Hindi, the language spoken in North India? Non-Hindi speakers sought the continuance of English on the grounds that it would not create invidious distinctions. Making Hindi the official language would give an unfair advantage to those with Hindi as their native language, they said.

The debate over language was sparked off at the very beginning of the CA session. Guha points out that on December 10, 1946 itself, a Hindi-speaking member, R.V.Dhulekar, declared: “People who do not know Hindi have no right to stay in India. People who are present in this House to fashion a constitution for India who do not know Hindustani are not worthy to be members of this Assembly. They had better leave.” This created an uproar in the House.

Many Hindi-speaking members demanded that every clause of the constitution should be presented to them in Hindi to enable them to participate in debates. They would not adopt a constitution written in a foreign language. But the Madras member T.T.Krishnamachari warned the Hindi zealots that if they wanted India to be united, they should shed “Hindi imperialism” and pointed out that there was already a separatist movement in the South, the Dravida Nadu movement.

Finally, the CA adopted a compromise solution. It made Hindi the official language of the government of India and added that English would be the associate language for the next 15 years. But after the violent anti-Hindi agitation in Tamil Nadu in 1965, the transition to “Hindi only” was put in abeyance indefinitely.