As COVID-19 Goes Global, New Risks Increase Across The World – Analysis

In addition to the Chinese mainland, the struggle against the new cases and outbreak clusters of the COVID-19 is shifting to countries outside China – not just Asia, but Europe, North America, the Middle East and Africa.

In China, the number of confirmed coronavirus cases is about to exceed 80,000, but the momentum of new outbreaks is now shifting to countries outside China, where the number of confirmed cases soared to almost 1,800 with 17 deaths.

This is only a prelude to what’s yet to come, however.

New virus risks outside China

While these numbers will continue to climb, the low starting-point suggests China’s draconian measures may have saved many lives within and outside China. The same cannot be said about preemption measures outside China’s borders.

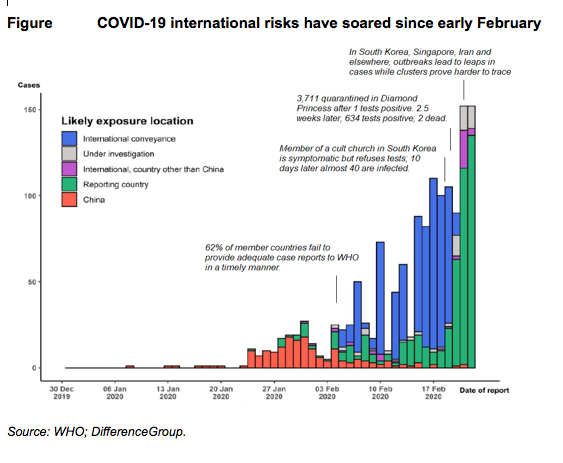

Risk of international complacency (WHO member states). On February 4, the WHO’s chief Dr. Tedros said that, after almost a month of international crisis and global alert, three of five WHO member countries outside China had failed to provide adequate information in a timely manner. As the timeline suggests, the number of cases outside China soared after February 4 and the missed opportunities of greater international cooperation (Figure).

Risk of botched quarantines (Diamond Princess Cruise). On February 3, more than 3,700 passengers and crew were quarantined by the Japanese Ministry of Health after one passenger on the ship tested positive for COVID-19. Just two and half weeks later, some 635 passengers tested positive for the virus, while two passengers had died after contracting the virus.

Risk of “super-spreaders” (South Korean cult church). From the start, potential super-spreaders who could endanger others have been a great concern. On February 10, a 61-year old woman, who worships at the Daegu cult church, developed fever but twice refused to be tested for the virus claiming she had not recently travelled abroad. After she had attended at least four services before the diagnosis, 40 other members of the church were infected.

Risks of potential evacuation failures (State Department vs CDC). As countries seek to rescue citizens from infected territories, failed evacuations can pose new risks. Last week, the US Centers for Disease Control urged to keep 14 infected US citizens in Japan, yet the State Department put the infected on a plane with healthy people claiming that a plastic-aligned enclosure would mitigate infection risks.

Risks of poorly-monitored self-quarantines (several countries). On February 21, California health officials said that 7,600 people who had returned to the state after visiting China during the virus outbreak had been asked to quarantine themselves at home this month. Laxness in self-quarantine could endanger far more lives. However, the CDC is not tracking how many people from each US state who have returned from China have been asked to isolate themselves. Further, local health departments have discretion in how to carry out the quarantines.

Unknown risks

In addition to the threats that we know, there are potential, more challenging risks which we understood poorly or don’t even know about.

Risks of untraceable virus clusters (several countries). In South Korea, Singapore and Iran, virus clusters have led to rapid leaps in cases. As it is becoming harder to trace where the clusters started, the virus may be spreading too broadly for traditional public-health steps to contain it. That highlights the importance of Chinese standard-setting measures that several countries are now emulating in part or fully.

Risk of real incubation period (faster, longer than presumed). Initially, clinical evidence suggested that the incubation period was 2-14 days, which then became the standard for quarantine measures. In the past weeks, Chinese authorities have extended these periods because new evidence suggests that, with possible outliers, the incubation period could be 0-27 days.

Risks of weaker healthcare systems (poorer developing countries). In late January, the WHO declared the ongoing virus outbreak a “public health emergency of international concern” (PHEIC). The goal was to boost international coordination against the expected internationalization of the outbreaks. As WHO officials have repeatedly noted, the PHEIC was motivated by the possible effects of the virus, if it would spread to countries with weaker healthcare systems.

In addition to proximate Asia, virus clusters have emerged in emerging Asia, big European economies, North America, Middle East, and Russia. Even though Italy has been the only European country to have barred flights to and from China, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan, it has seen a dramatic increase of cases, centered in the regional towns of Lombardi, near Milan – the country’s business hub.

The world’s most vulnerable

The big question is how forcefully the virus will arrive in the rest of Americas and particularly Africa.

Risks of local transmission. On Feb 21, when the virus had spread to 25 countries, local cycles of transmission had already occurred in 12 countries after case importation. In Africa, Egypt has so far confirmed one case. As such cases are expected to proliferate, the probability of such risks will climb accordingly.

In modeling simulations based on air travel, new research indicates that the highest importation risk involves a set of countries – including Egypt, Algeria, and South Africa – that have moderate to high capacity to respond to outbreaks. In turn, countries at moderate risk – including Nigeria, Ethiopia, Sudan, Angola, Tanzania, Ghana, and Kenya – have variable capacity and high vulnerability.

Several African countries are already struggling to contain another Ebola virus outbreak, while others are fighting the worst locust in decades. Having already decimated crops throughout Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia, Eritrea and Djibouti, locust swarms threaten South Sudan, Uganda and Tanzania, while breeding along the both sides of the Red Sea in Egypt, Sudan, Eritrea and Saudi Arabia.

Old risks could resurface along with the new

As new risks are evolving, old risks are not yet fully contained and can still pose lingering threats in China and particularly in countries outside China.

Risk of “closed spaces” (prison systems, nursing homes). On February 21, Chinese prisons reported some 500 new cases of infections among inmates and guards. It was followed by news of infections in nursing homes. Both cases highlight the high transmissibility of the virus in spaces of confinement.

Risks of new potential mutations and infection scenarios. The plausible current assumption is that, like seasonal influenza, the COVID-19 is causing mild and self-limiting disease in most people who are infected, with severe disease more likely among older people or those with comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, pulmonary disease).

But if the scenario changes towards wider community transmission with multiple international foci (or toward new kind of mutations), current mitigation procedures will prove inadequate and countries will be more likely to emulate Chinese measures.

Based on Dr. Steinbock’s briefing of Feb 23, 2020, on COVID-19 human and economic impact.