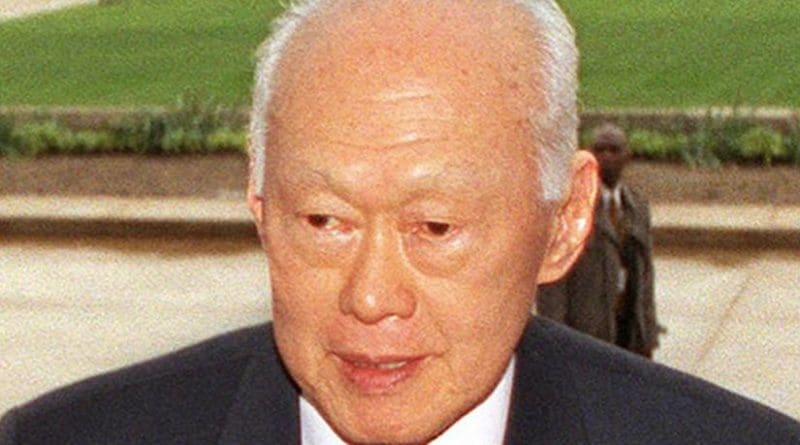

Lee Kuan Yew And Singapore’s Foreign Policy: A Productive Iconoclasm – Analysis

By RSIS

Lee Kuan Yew’s mark on Singapore’s foreign policy is that of applying counterintuitive strategies to improve the island state’s international standing. In retrospect, this has ensured Singapore’s long term viability as a sovereign nation-state.

By Alan Chong*

As Singapore’s first Prime Minister and the point man in negotiating decolonisation from Britain in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Lee Kuan Yew carries an aura of being one of the pioneers of the island state’s foreign policy. His political personality appears to have been directly mapped onto his steerage of foreign policy: cold unflinching appraisal of one’s circumstances, and self-reliance in designing one’s survival strategies, but only up to the point that external parties can be persuaded that it is in their conjoined interests to partner Singapore in pursuing win-win collaborations.

Lee’s autobiography reveals the profile of an energetic, enterprising young man who was confronted with a series of personal challenges in adapting to material scarcity and political brutality, especially during the Japanese Occupation. This was a key formative influence for foreign policy born of dire geopolitical and geoeconomic circumstances.

Not a normal country

Independent Singapore, bereft of a reliable hinterland constructed by the British empire, was literally perceived by its leaders as an island unto itself, surrounded by similarly decolonised but territorially larger nation-states. The initial decade of transiting from colony to independence from 1959 to 1965 was traumatic on a national level. By his own admission, Lee’s initial view that ‘island states were political jokes’ had to be reversed to achieve the impossible. His strategy for a sound foreign policy was to think unconventionally, and in word, to act as an iconoclast – a leader who sets the pace for his followers with a knack for the counterintuitive.

In his own reflections in 2011, following three decades as Prime Minister, then Senior Minister and Minister Mentor, he emphasised the need for Singaporeans to grasp foreign affairs: ‘I’m concerned that Singaporeans assume that Singapore is a normal country, that we can be compared to Denmark or New Zealand or even Liechtenstein or Luxembourg. We are in a turbulent region. If we do not have a government and a people that differentiate themselves from the rest of the neighbourhood in a positive way and can defend ourselves, Singapore will cease to exist. It’s not the view of just my generation but also those who have come into Defence, Foreign Affairs Ministries and those who have studied the position’.

Already in 1966, he was urging students at the then University of Singapore to aspire to bigger dreams in their careers. This would add value to Singapore by enticing the world to take interest in its industry, development, standards of living and sometimes, sheer intellectual insights. He went on to argue that once the great powers and Asian states planted intellectual, scientific and commercial stakes in the island state, Singapore’s fundamental security would be assured indefinitely.

In this sense, Lee shared with his friend and PAP comrade, S. Rajaratnam, an affinity for global imagination – Singapore could literally treat the world as its hinterland if its people and their technical skills were capable of servicing the world’s niche requirements in banking, telecommunications, R&D and indeed diplomacy.

Lee the Philosopher of Foreign Policy

As Lee would have it, international affairs were all about leadership and the making of either good or bad decisions. In a less publicised speech at the Australian Institute of International Affairs, he set out the view that ‘“International Affairs” is as old as the subject of man…[T]he essential quality of man has never altered. You can read the Peloponnesian Wars, you can read the Three Kingdoms of the Chinese classics, and there’s nothing new which a human situation can devise. The motivations of human behaviour have always been there. The manifestations of the motivations whether they are greed, envy, ambition, greatness, generosity, charity, inevitably end in a conflict of power positions. And how that conflict is resolved depends upon the accident of the individuals in charge of a particular tribe or nation at a given time.’

On hindsight, this was more than a fitting epitaph for the first prime minister of the Republic of Singapore. It was a statement of a belief in the possibilities of forging one’s own destiny. We call it today the Singapore Dream of peace and stability, folded into the SG50 milestone of progress and prosperity. Singapore’s foreign policy under Lee’s astute sense was certainly man-made.

Lee’s approach to foreign policy has always been guided by a quixotic mixture of principles of anxiety, nationalistic zeal, and an earnest attempt to dovetail the national interest with some universalist principles circulating in the international order. These compass points have not been clearly prioritised for ostensible reasons of bureaucratic and diplomatic flexibility, and therein lies Lee’s talent for discerning the best path forward for Singaporean foreign policy.

Correct outcomes, not political correctness

Although Lee has never publicly referred to his role in forcing a decision on any particular foreign policy issue, he has never shied away from suggesting that his personal diplomatic heft has enabled him to convey national messages directly to his opposite numbers in foreign governments. The tone of his remarks on relations with China, Taiwan, Indonesia, Malaysia, the United States and Vietnam in his memoirs suggests that his presence as the authoritative decision maker mattered to foreign perceptions of who could effectively steer policies for Singapore.

As Singaporeans and the world mourn the passing of a giant of twentieth century Asian politics, we will do well not to forget that Lee Kuan Yew was never one to entertain political correctness. He was more concerned with producing correct outcomes even amidst the vagaries in international politics. Perhaps the final reflection should be reserved for Lee’s views on something as controversial as the US intervention in Iraq early in the 21st century.

Despite American dismay over their post-invasion quagmire in rebuilding Iraq in 2003-2012, Lee encouraged the US to complete their mission, notwithstanding his government’s initial disapproval of George W. Bush’s invasion plans, since fundamentalist Islamic terrorists in Southeast Asia and elsewhere would take heart from an outright American withdrawal.

The erstwhile US Ambassador to Singapore conceded a grudging respect for Lee’s sagacity in a confidential cable in 2006 under the subheading ‘Welcoming the United States, but not our politics’. This is Lee Kuan Yew the successful iconoclast.

Alan Chong is Associate Professor of International Relations at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University. He has just published a study in an academic journal comparing Lee Kuan Yew and Mahathir Mohamad as exemplars of authoritative decision makers in foreign policy. This is the third in the series on the Legacy of Lee Kuan Yew.