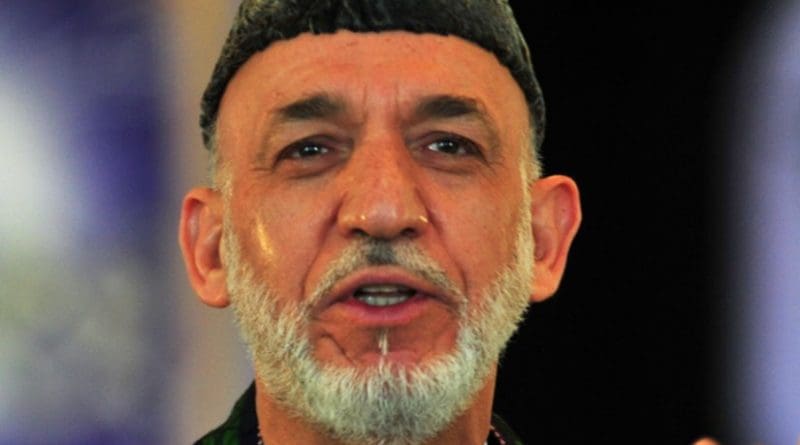

Karzai Visits United States: A Mutual Opportunity To Bury Hatchets?

By Dr. Shanthie Mariet D Souza

The recent visit of President Karzai to Washington DC brought to the fore the differences that have frayed the relationship under the new US administration, at a time when they need each other the most. The fraud-marred 2009 Afghan presidential elections and the subsequent repeated hurling of accusations of cronyism, inefficiency and corruption of the Afghan government by the Obama administration, had strained the relationship between the two countries. President Karzai too had lashed out at the foreign involvement in the elections and repeatedly pointed at the mounting civilian casualties. He visited China, hosted the Iranian president and even threatened to join the Taliban, none of these actions were music to Washington’s ears. Obama’s public lecturing in Kabul during his March 2009 unannounced visit to Afghanistan looked like another step downhill.

Karzai enjoyed a rather close relationship with President Bush, whereas his ties with President Obama are at best ‘distant’. His relationship with Obama’s two key administration emissaries – Richard C. Holbrooke and Karl Eikenberry remain strained. He has clashed with Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr over issues of corruption in the Afghan government. The only exception being the top US military commander in Afghanistan, General Stanley A. McChrystal, with whom Karzai shares a close relationship.

In a way, these tensions are reflective of the internal stresses within the civil and military component of the American-Afghan team, including friction between Eikenberry, American Ambassador to Afghanistan and the military, and between Holbrooke and the White House. These stresses have further exacerbated in the absence of a coherent strategy and consensus of the means to address the present quagmire Afghanistan.

Even with his serious differences with the Obama administration, President Karzai is obliged to take the first step to make amends, for the US aid and support remains crucial for Afghanistan’s reconstruction and recovery. Reports indicate that the Afghans are pressing the Obama administration to designate Afghanistan ‘a major non-NATO ally’2, a status enjoyed by Japan, Australia, South Korea, Israel, and more importantly – Pakistan. The designation brings with it access to the US military technology and other benefits. Afghans also want to ‘update the US-Afghanistan strategic partnership agreement of 2005’,3 and in line with the recently held US-Pakistan strategic dialogue, are vying for greater US commitment and resources long after the summer of 2011. The establishment of the US-Afghan strategic dialogue is seen as a step in that direction.

If ‘kiss and make up’4 is a matter of compulsion for Karzai, for Obama too, it is a choice between the devil and deep blue sea. With less than a year to go before the announced exit, the Obama administration appears to have come to terms with dealing with the de jure power centre in Kabul. After a year of sniping, realisation seems to have dawned in the US policy-making circles about the need to maintain working relationship with Karzai. Given that the US troop numbers would rise above 100,000 in that country by 2011 and for the draw down to actualise in the stated time frame, it is imperative that Afghans take the lead. For this, enhancing Karzai government’s capacity and credibility would be crucial.

A Pentagon report submitted to Congress in April 2010 said that the security situation in Afghanistan has improved from what it was a year ago although it can be sustained only through the Afghan government’s ability and willingness to expand governance to areas that international forces clear of Taliban. In light of the troop increase and heightened military activity, the US is now spending more in Afghanistan than Iraq, for the first time since 2003. In February 2010, Pentagon spent US$6.7 billion in Afghanistan compared with US$5.5 billion in Iraq. For the fiscal year 2008, Iraq was three times as expensive and in 2009, it was twice as costly.5

Having announced a troop surge and an arbitrary date for the drawdown of forces, President Obama has a limited window of opportunity to demonstrate success to his domestic constituency where public opinion in support of the war is waning. The new counter-insurgency approach has not turned the situation around as quickly as President Obama had hoped. The lack of capacity of the Afghan state and uncoordinated international development efforts have been a force multiplier for the rapid spread of the insurgency and has largely undercut General McChrystal’s counter-insurgency strategy, which has sought to gain the support of the Afghan population. The result is a quagmire in which ‘nobody is winning’,6 as General McChrystal admits.

As the recent Operation Moshtarek at Marjah demonstrated, concerns remain about shoring up local government capacity to ‘hold’ on the cleared area. For instance, General McChrystal’s ‘government in a box’ idea for a local Afghan government that would start functioning and delivering in former Taliban stronghold of Marjah once the US troops cleared out the insurgents has not taken off. The Marjah campaign offers important lessons for the upcoming offensive in Kandahar this spring, described as ‘decisive’, in the overall Afghanistan war effort. The US efforts of improving local governance in Kandahar will have to be done concurrently with clearing operations. Good governance through strengthening government at the district and local levels would remain central to the operations attempting to dislodge the Taliban control. However, reining in Karzai’s controversial half brother, Ahmed Wali Karzai, tainted with charges of corruption and drug trafficking who wields enormous power as the chairman of the provincial council, would require Karzai’s good offices.

Karzai is seeking the US support for his plan for reconciliation with and reintegration of the Taliban, an attempt at fracturing the insurgency at a time when the US military action is slated to intensify and before the US withdrawal. Ahead of the peace jirga (consultative assembly) to be held on 29 May 2010, Karzai has managed to get a pledge that most of the Afghan detainees will be transferred from North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) to Afghan custody. As the military stalemate continues, many allies like France, Holland, Britain, Germany and Italy are under intense political pressure at home to begin withdrawing from Afghanistan, providing increasing credence to the talks of negotiating with the Taliban. The forthcoming peace jirga is an outreach effort to some 1,500 Afghan community leaders to discuss the way forward in reconciliation. Likewise, the talks to negotiate a broad agreement with the Taliban leadership that forms a national unity government and guarantees that Al-Qaeda and other radical groups do not return to Afghanistan, are gaining currency in the Western policy-making circles.

While civilian deaths from aerial bombings have declined, American officials now admit shootings of Afghan civilians by American and NATO convoys and at military checkpoints have spiked sharply this year, becoming the leading cause of combined civilian deaths and injuries at the hands of Western forces.

According to the US military statistics, at least 28 Afghans have been killed and 43 wounded in convoy and checkpoint shootings this year – 42 per cent of total civilian deaths and injuries and the largest overall source of casualties at the hands of American and NATO troops. The shootings alienate Afghans, who see them as proof of impunity with which the international forces operate. The US is seemingly taking steps to address these issues. Military commanders are issuing new troop guidelines that include soliciting local Afghan village and tribal elders and other leaders for information to prevent such convoy and checkpoint shootings.

Not surprisingly, the public criticism of Karzai government has been toned down. There is much less reference now to the prevailing level of corruption, inefficiency of the administration and the drug trade. The US Ambassador to Afghanistan Eikenberry, who had warned against the troop surge and had denounced Karzai in a diplomatic cable last year as not being ‘an adequate strategic partner’7, personally escorted Karzai on the flight from Kabul to Washington. In contrast to the visit last year where Karzai had to share the spotlight with Pakistan President Asif Ali Zardari, the US administration this time rolled out the red carpet for Karzai, who arrived with nearly 20 members of his cabinet. Amidst much fanfare and symbolism, President Karzai attended a state dinner with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, met with President Obama, and had a formal head of state press conference at the White House.

In its desperation to find a solution from the present morass, the Obama administration is more than willing to bury its hatchets with Karzai. For the beleaguered Afghan President too, it is a matter of the US support or deluge. Circumstances do necessitate such strange alliances.

Dr Shanthie Mariet D’Souza is a Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore. She can be contacted at [email protected]. The views reflected in this paper are those of the author and not of the institute (ISAS), where this article was published (PDF) and is reprinted with permission.