Of Ranks And Scores In Nuclear Security: 18 Years Of South Asian Nuclearisation – Analysis

By IPCS

By Rabia Akhtar*

In the foreword of the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI) Index 2016, Sam Nunn, NTI Co-Chairman and CEO, asked an important question in the context of the last Nuclear Security Summit (NSS) held in Washington, DC: “Without the high-level attention and impetus provided by the summits and with so many competing priorities in a deeply unsettled world, can governments remain focused on the need to tighten nuclear materials security?”

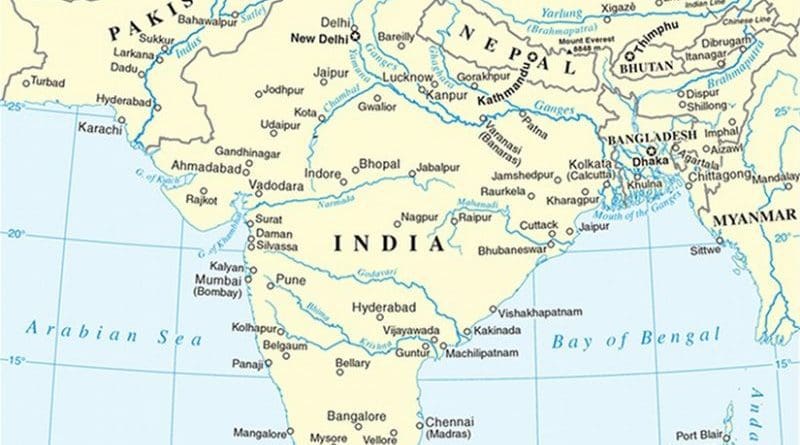

It is true that the global threat environment has worsened over the last decade but measuring the performance of mature and stable nuclear weapons states (NWS) against new and developing NWS seems like an unfair comparison. India and Pakistan are in their eighteenth year of nuclearisation and in this time period, these two countries have not only institutionalised robust command and control structures but have also developed an efficient nuclear security culture, established export control regimes in their respective countries, and have worked with the IAEA and other nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament initiatives to strengthen the very regime that has kept them out as pariahs.

Between the de jure nuclear weapons states, there is rich nuclear experience equivalent to a cumulative 310 years, broken down individually to: 71 years of US nuclearisation; 67 of Soviet/Russian; 64 of British; 56 of French and; 52 of Chinese. Moreover, the US has provided nuclear weapons to non-nuclear NATO countries as part of nuclear sharing, a practice that violates the principles of the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) by transferring direct or indirect control over nuclear weapons to non-nuclear countries.

Running nuclear weapons enterprises as old as the five de jure NWS have been, it should come as no surprise that almost all of them have an overall score of 60 and above out of 100 in the Theft and Sabotage NTI Index 2016, with the exception of China, which has an overall score of 60 in Theft and 59 in Sabotage. Given their cumulative and individual years of experience, one would think they would score almost 100 out of 100 but that is sadly not the case. Their individual ranking out of 24 for Theft and out of 45 for Sabotage is also not that spectacular given the years of experience they have had in institutionalising their nuclear safety and security regimes. In the Theft Index, the US ranks at number 10, Russia 18, UK 11, France 8 and China 19, and 6, 22, 3, 10 and 34, respectively in the Sabotage Index. It seems that only France fares better in individual ranking above others and would make an interesting case study.

In comparison if one must, after merely eighteen years of nuclearisation for both countries (42 years for India if 1974 nuclear test is taken into account) India ranks 21 and Pakistan ranks 22 out of 24, with an overall score of 46 and 42 out of100 respectively in Theft. They rank 36 and 38 out of 45 with an overall score of 55 and 54 out of 100 respectively in Sabotage. These are not just numbers. These numbers tell a remarkable story. These numbers demonstrate that even with “competing priorities in a deeply troubled world,” to be specific, in the most deeply troubled region, both countries have shown incredible commitment towards securing their nuclear facilities, materials and personnel.

What is the way forward for these two countries in the absence of a multilateral forum like the Nuclear Security Summit? The prospects of establishing bilateral nuclear security mechanisms between the two are not too bright given the historic mistrust towards each other. Moreover, India will not sit down and share its best practices with Pakistan on nuclear safety and security if China is not part of any such arrangement.

These three NWS share a common border and are uniquely situated against each other, where theft or sabotage of nuclear facilities and materials in one country can create an emergency situation in other’s backyard. The threat of nuclear terrorism is real and should be acknowledged as such. The entry into force of the Amendment to the Convention on Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (CPPNM) on 8 May 2016 is a testament to the fact that states need to improve physical protection of nuclear material and facilities ‘in peaceful domestic use, storage and transport’. India, China and Pakistan are state parties to CPPNM and this is one platform on which these three countries can cooperate to reduce each other’s vulnerabilities to nuclear terrorism.

Since India and Pakistan cannot initiate a bilateral mechanism between them, China would have to take the lead to bring both countries together to develop a regional trilateral network for biannual meetings initially to develop trust and discuss regional threat scenarios related to nuclear terrorism that could affect each country equally. China’s ranking and overall score according to the NTI Index 2016 makes it the lowest ranking de jure NWS, but it fares better than India and Pakistan in the Theft Index and marginally so in the Sabotage Index. It is therefore in China’s interest to initiate such a trilateral conversation where each country gets to learn from the other to make South Asia a safer place for all.

* Rabia Akhtar

Director, Center for Security, Strategy and Policy Research at the University of Lahore, Pakistan

Email: [email protected]

History is key to making sense of the utility of nuclear weapons to Pakistan, and the state’s heavy reliance on them. A point that is often ignored is that India went nuclear even when there was no need for it.Moreover, history has shown that what matters in terms of risks is not whether or not a country has nuclear weapons, but what it intends to do with them. And that we often don’t exactly know. An example can be that of India when it conducted a “peaceful nuclear explosion,” in the early 1970s. This was seen then as hard proof that India was looking to become a nuclear power, given the country’s long feud with Pakistan. For the same reason, as a deterrent to India, Pakistan developed itself into a nuclear- weapon state.