The Improbability Of Peace In Syria – Analysis

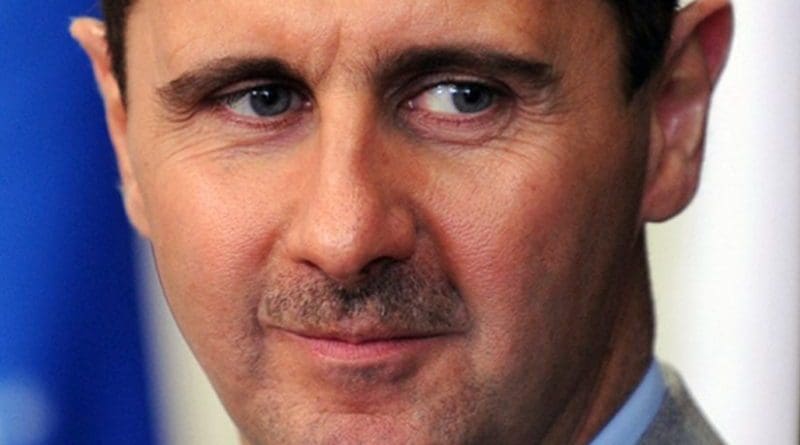

The regime of President Bashar al-Assad now effectively controls only about one-sixth of the territory of original Syria and its control is diminishing on a daily basis because it is losing territory to insurgents and facing a manpower shortage in the military.

Until recently the regime continued to hold the core urban centres across the country while letting the countryside, mostly desert, be controlled by the opposition groups including the Islamic State (IS). On 26 July, Assad admitted that the regime had difficulty in holding on to all the provincial centres that it had so far endeavoured to do and that it would now concentrate available military resources on securing the Damascus-Homs-Hama-Latakia coastal belt in the west. The IS is attempting to move into the regions that have been abandoned by the regime. The undeniable fact is that Syria has already been dismembered into several ‘fiefdoms’.

The Syrian Civil War has now been raging for four years and there does not seem to be any end in sight. The major participants are the Assad regime and its primary supporters Iran and Hezbollah, the IS, Turkey, the moderate Southern Front, the Saudi Arabia sponsored Islamic fundamentalist group Jaysh-al-Fatah and the al Qaeda affiliate Jabhat-al-Nusra. In addition the Kurds are extremely active as are the Western nations fighting an air war against the IS. Somehow, if these groups could be aligned into two distinct camps it may have been easy to understand the civil war. Unfortunately each one of these entities have different and self-serving objectives and, perhaps more importantly, are at odds with each other.

The Assad regime is essentially fighting three main enemies—the IS, which holds almost half of Syrian territory although much of it is desert; the Islamic rebel coalition Jaysh-al-Fatah that is supported by Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Qatar; and the Southern Front, a moderate opposition coalition that holds much of the south of Syria. The regime is supported by Hezbollah and both have suffered heavy personnel losses to an extent that they can no longer carry on a three-sided conflict. They seem to have therefore decided to let the IS fight the other Islamic groups and the moderate opposition.

Assad’s calculation in doing so is not difficult to fathom—if and when the IS is able to defeat the other groups, the international community will come to his aid to fight the scourge of IS. This sequence of events can only be considered a pipedream, fundamentally because of the fact that if IS remains the only opposition to the regime, the international forces are unlikely to fight to keep Assad in power. The only reason he is allowed to continue to hold on to some vestige of power is because the international community does not want the IS to fill the vacuum that would be left in the wake of the removal of Assad. Therefore the current tactics of letting the IS fight the others is bound to fail in the long term.

The Southern Front

The only remaining moderate opposition to the regime is the Southern Front, which openly renounces extremism. From a military perspective this group is relatively well organised and has support from the US and some European countries. The Front controls the provincial centre Daraa about 100 kilometres from Damascus. The changed tactics of the regime has facilitated the IS to take on the Southern Front, indicated by the situation on the ground where from early 2015 almost all the battles that the Southern Front has fought have been against the IS—the regime and Hezbollah are not engaged anymore.

The Southern Front is now the only moderate group that can stand up to Jaysh-al-Fatah and other more fundamentalist groups. To its credit, it has provided ethical guidelines for its members and has also established a political wing in preparation for an anticipated political role in the inevitable transition that has to take place in Syria. The Front works closely with the local civilian councils in the areas that it controls and has managed to gain the trust of the citizens, much more than any other group. This has resulted in people joining the group not out of ideological support, but in order to ensure social order and stability in today’s extremely turbulent time.

Further, the Southern Front hopes to wean members of the less fundamentalist groups to join them, although this might require greater financial capabilities since other groups, especially the Jaysh-al-Fatah provide financial incentive to its members. The Front needs greater financial and military assistance if it is to prevail against the better supported groups.

Saudi Arabia and Jaysh-al-Fatah

Since the beginning of the war against IS, Saudi Arabia has felt that the flagging of its regional influence. The situation was exacerbated by the US-Iran deal that led to the international community’s acceptance of the Shiite nation and Iran’s increasing influence in the region. Saudi Arabia expects that removing the Syrian President, who is supported by Iran, from power would bolster its position and lead to greater regional influence. The Islamic group Jaysh-al-Fatah was created by Saudi Arabia as a pragmatic response to the US ambivalence regarding a regime change in Syria, which from a Saudi Arabian viewpoint is critical to improving their influence and to achieve any further progress in resolving the conflict.

Even in the creation of one more fundamentalist organisation, Saudi Arabia is playing its usual double-game. It supports the Southern Front against the regime in Southern Syria while actively involved in supporting the Jaysh-al-Fatah in the north and also trying to create a branch to function against the Southern Front in the regions under its control.

Riyadh also wants Jaysh to be independent of Jabhat-al-Nusra, the Syrian franchise of al Qaeda. This requirement is being emphasised since currently there is some amount of affiliation between the two groups. Only with complete delinking of the two can Saudi Arabia and Qatar hope to have predominant influence in the post-Assad Syria. If the Jaysh-al-Fatah manages to outgrow the Southern front, it will become the most influential militia inside Syria and will play a significant role in Syria after Assad is removed, a situation that will effectively sideline all other moderate groups.

Jabhat-al-Nusra, the al Qaeda affiliate is sensibly moderate in its approach to the conflict, but also harbours political ambitions. However, the group has also made it clear that its objectives are restricted to being an influential element within Syria and that it does not entertain any global ambitions. Its fundamental political objective is to influence Syria’s transition and to ensure that it becomes an ‘Islamic’ nation.

The Turkish Factor—Kurds and IS

From the beginning of the US involvement in the Syrian Civil War the US has concentrated on defeating the IS, while Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar have focused on ousting Bashar al-Assad. While the US has supported the Kurds as ‘effective partners’ on the ground in the fight against IS, Turkey and the others supported opposition militia in their fight against the Assad regime. However, there is no unified command amongst these militia to achieve the removal of Assad and there is no consensus regarding the shape of the post-Assad Syria.

Ankara is the joker in the pack, with President Erdogan steadfastly insisting on Turkish hegemony over a transitioned Syria. Turkey perceives Syria and the Kurds as the fundamental threats to its security. The US disagrees with this assessment but have not been able to convince Turkey that defeating the IS is critical for any other regional initiative to succeed. Till such times as Turkey joined the military alliance against Syria and started taking part in the military operations, it was banking on the Islamic groups who were sympathetic towards Turkey and operating in Syria to remove Assad from power.

Although the Kurdish militia has been the most effective fighters against IS on the ground, Erdogan has reopened the Turkish civil war with the Kurds instead of attempting to achieve a negotiated settlement for a more durable peace. Currently the official chatter in Turkey is about the ‘Kurdish threat’ to national security, encouraged by the AKP government to achieve its declared aim of preventing the formation of an independent Kurdistan. The AKP government is pursuing the perpetuation of dual tactics. One, to create a ‘buffer zone’ in northern Syria so that the land area controlled by the Syrian Kurds will not be contiguous to set up an autonomous Kurdish state; and two, rounding up Kurdish activists within Turkey to prevent them from initiating any action towards a ‘greater’ independent Kurdistan.

Turkey finally entered the war last month (July 2015), after four years of siting on the sidelines and cheering the wrong teams. It faces two direct threats along its southern border—the IS and the Kurds. The IS controls large swaths of desert between Aleppo in north-west Syria, Mosul in northern Iraq and Ramadi in the south near Baghdad.

Turkey denies abetting the rise of the IS, although they maintained a porous border from 2012 to 2014 and turned a Nelson’s eye to the influx of large numbers of weapons and foreign fighters crossing it to join the IS. This was obviously done in the mistaken belief that the IS would have an easy victory over the Assad regime. They did not cater for the tenacity of the Syrian government and the support it would receive form Iran and the Hezbollah. Turkey also stoked the anti-government resentment of the Sunnis in Iraq by repeatedly accusing the al-Maliki government of having a Shia bias. Turkey has consciously attempted to destabilise Iraq through increased support for IS in Iraq and more importantly through its support for Kurdish autonomy in northern Iraq. Turkey continued to aid both the Kurds and IS by buying oil from them, over al-Maliki’s protests. The Frankenstein is now coming home to roost.

Turkey had undertaken a brutal repression of domestic Kurds in the 1980s and 90s, who still account for about 20 per cent of the population. It is also noteworthy that the Kurdish rate of population growth is higher than the national average and therefore this percentage is likely to increase into the future.

Apart from Turkey, the Kurds are spread over Syria, Iraq and Iran with their fight for independence starting to gain traction with the arrival of IS into the fray. Currently the Kurdish controlled areas of Iraq and Syria can be considered almost a single entity. Turkey has realised that the Iraqi-Syrian Kurds are now far advanced in their quest to be an autonomous State and are fearful of the influence it will have on their own Kurdish population. Turkey fears that it may not be able to stop Turkish Kurds from joining their brethren. If this happens, it would translate to the loss of about a quarter of Turkish territory where Kurds are in majority. Such a turn of events, would see Turkey losing its common borders with both Iraq and Iran and suffering a commensurate decrease in its regional influence.

This is where the Turkish demand for the ‘buffer zone’ comes into play. It is significant that the creation of a ‘buffer zone’ has been Turkey’s fundamental demand from the beginning of the Syrian Civil War and denial of which was primary reason for Turkey so far not joining the fight. Turkey has a two-fold aim in the creation of this zone, nominally north of Aleppo in areas currently controlled by IS—one, push the IS away from its southern borders while filling up this ‘safe zone’ with Syrian refugees; and two, by doing so they will prevent the Kurds from linking the eastern and western parts of the territories that they control. Logically such a buffer zone should be controlled by the Kurds since it lies in Syria and is essentially a part of the Kurdish territory but Turkey will not let them take control. In combination with the domestic crackdown on Turkish Kurds, this situation could lead to a sub-conflict in the region.

Turkey has also calculated that if the ‘buffer zone’ is established then the Jabhat-al-Nusra will be able to concentrate fully against the Assad regime, because the IS will not be able to attack it from its flanks. This is a secondary bonus in Turkish calculations since their primary aim remains the removal of the current Syrian regime from power. Turkey is essentially superimposing its domestic political compulsions on the Syrian Civil War. This is Erdogan’s risky gamble, since it can benefit Turkey only to a point—the Kurdish issue cannot be swept under the carpet nor can an ostrich-like attitude lead the way to peace and stability. Return to the negotiating table with the Kurds can only happen after the train of events that Erdogan has set in motion runs its course and much blood—both Turkish and Kurdish—is spilt on the streets and sand of Turkey.

Iran’s Peace Initiative

The Iranian foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, has put forward an updated version of an earlier peace proposal, which has a four-point agenda: cessation of hostilities within Syria; a five-year transition period; retention of Syrian sovereignty; and the expulsion of all foreign terrorists from Syrian territory.

Unlike the last time, this proposal is likely to be debated seriously by the major parties involved because of two factors—Iran’s greatly improved status and re-entry into mainstream international politics following the ‘nuclear deal’; and the extensive consultation that was done with Qatar, Kuwait, Lebanon and the Syrian regime itself before the plan was announced in public. The plan is for extensive political dialogue to be conducted among the Syrian people when physical combat ends in order to chart an acceptable way forward.

The problem with the Zarif Plan is; first, the difficulty in enforcing the cessation of fighting considering the wildly different hues of the parties involved, second getting Turkey on board, and third, creating a transitional Syrian Government acceptable to all. The need, as everyone recognises, is to arrive at a negotiated settlement. The longer the conflict lasts, greater are the chances of the IS increasing its influence in failing Syria.

Even Russia, so far a staunch supporter of Assad, recognises that Syria could rapidly become IS country and therefore it is common sense to unite against the IS. The transitional government, if it ever gets established, needs to have representation across the Syrian political spectrum and should include the opposition diaspora as well as members of the current regime willing to shift their stance. It has to be a compromise solution and must avoid all the challenges that Iraq faced when a less than optimum solution was foisted upon the people after the 2003 invasion.

The antagonism inherent in the Turkey-Kurd relationship complicates the implementation of the Zarif Plan. The Plan also discounts the fact that the IS will not negotiate with any of the other groups or countries involved and must therefore be defeated in order for the peace process to proceed. Turkey holds the key at the moment to the way forward. However, at least for the moment it seems that unless the Kurdish issue is sorted out Ankara will continue the impromptu responses that it has so far put forward without any consideration of the long-term strategic consequences of such actions. At the absolute baseline the chances of establishing successful peace comes down to Turkey-Iran relations.

While their bilateral relations remain satisfactory and trade is gradually being boosted, the interventionist policy that Turkey is currently following may in the end become a bone of contention. The gravity of the situation in Syria requires secondary and self-centred interests to be set aside. The real threat remains the fact that the Syrian could rapidly engulf the neighbouring countries.

Conclusion

The Syrian conflict has not only dismembered the nation but has ravaged the greater Middle-East. While there has been continuous air strikes by the US-led coalition against the IS, no grand strategy has been articulated or is being followed. Containment as a strategy is an open admission of a dearth of imagination. Neither has any political agreement followed in the footsteps of all the diplomatic activity that has been carried out with more than adequate fanfare.

The challenge now is that the civil war is not a Syrian Civil War anymore, it is a Middle-Eastern Civil War in which the opponents are not clearly divided, where friends become foes and foes become allies in very short order, creating a confusing mosaic of half-truths and grey areas. There are far too many parochial interests being pushed and a number of proxy wars being fought in Syria, leading to the reluctant conclusion that a considered political solution recognised by all participants can never be achieved.

No one nation, group or alliance has the strength or quantum of force necessary to regain control over the lost territories in Syria in order to stitch together even a fractured State with geographic credibility. The US and its allies do not have a coherent strategy to bring about an acceptable solution so that the people of Syria can start to rebuild their ravaged lives. It seems inevitable that Syria will continue its path towards complete fragmentation. The threat of IS is real, but the complete dismemberment of Syria will have far greater consequences than what the IS currently pose in the region. Meanwhile as the world watches and waits—more than half the Syrian people have become refugees in their own country; their erstwhile ruler continues to bomb his own people; and the IS destroys millennia old artifacts in the name of religion. Syria’s death knell is audible, loudly and clearly.

The nations of the Middle-East and Turkey should be carefully listening the sounds and remembering the words of the 17th century poet John Donne, ‘Any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in Mankind; And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; It tolls for thee.’

*Dr Sanu Kainikara – Canberra-based military and political analyst – Visiting Fellow UNSW – Distinguished fellow IFRS First published in the Blog www.sanukay.com on 24 August 2015

Thanks for the detailed analysis. The neighbours pursuing their individual agendas without realizing the greater threat to their own survival is the most significant aspect of the crisis.