The Case Of The Gambia: A Template For Democratic Transition? – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Laura D’Aiello*

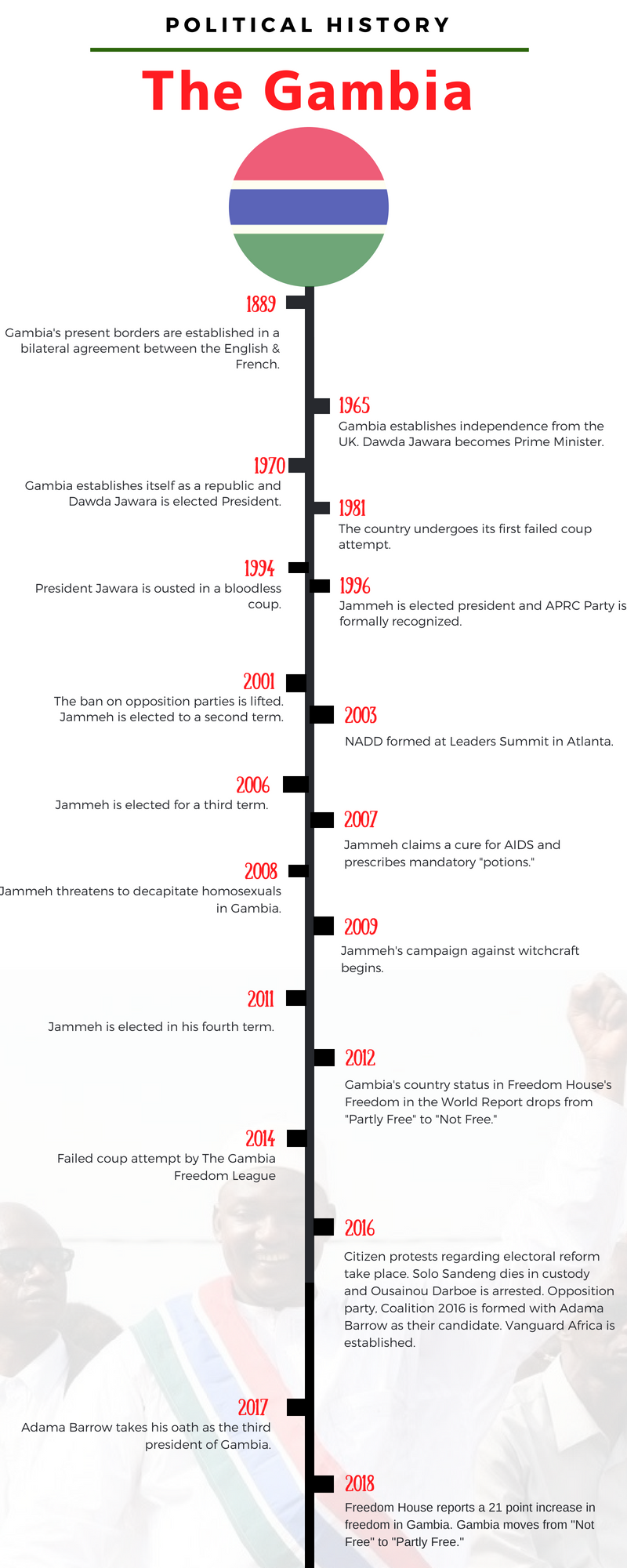

(FPRI) — On December 1, 2016, Adama Barrow took the small West African country of The Gambia by surprise when he won the country’s presidential election, and became the nation’s third president in over 51 years. Largely as a result of this transfer of power, The Gambia secured a record-breaking 21-point score increase in the annual “Freedom in the World 2018 Report,” moving from “Not Free” status to that of a “Partly Free” nation seemingly overnight. What key events led to such an unusually peaceful transfer of power in The Gambia? Can the lessons learned there be applied to other post-authoritarian transitions? Will The Gambia’s democratic breakthrough be sustained?

Background

The Gambia is one of the smallest and most densely populated countries in Africa. Its borders were established along the banks of the Gambia River in 1965, after gaining independence from the United Kingdom, and the country has functioned as the continent’s longest multi-party democracy since its independence.

However, in 1994, the nation’s first president, Sir Dawda Jawara, was overthrown in a military coup led by a young Lieutenant, Yahya Jammeh. Jammeh’s initial two-month-“interim”-turned-22-year rule was characterized by excessive human rights violations and repressive laws on freedom of expression, along with another classic authoritarian trademark: violent, unfree, and rigged elections. Violence and human rights violations escalated exponentially over the course of Jammeh’s presidency, and a heightened climate of fear in The Gambia attributed to a violent, failed military coup against him in 2014. This incident led to intensified government repression and violence, but also was a key factor in the organization of a successful opposition coalition and in the mobilization of Gambians to demand a new leader.

The Process to a Free and Fair Election: A Violent Catalyst

In April 2016, in anticipation of the coming December election, opposition activists held an unprecedented peaceful protest advocating for electoral reform. The Guardian reported this incident as “the biggest act of public defiance against the president since he took power.” Members of the main opposition party, the United Democratic Party (UDP), were arrested, and a prominent party leader and organizer, Solo Sandeng, was detained, tortured, and killed in custody shortly after the protest.

Once the news of Sandeng’s death became public, hundreds of citizens demonstrated in the streets, demanding the release of the remaining detainees along with Sandeng’s body. An editorial report on the 2016 protests from The Gambia’s online news source, Freedom Newspaper, read, “The impoverished nation of The Gambia, has been rendered economically and politically unstable, in view of recent political developments gripping the country. Protesters have taken over the streets. Hardly a day passes without people thronging the streets or court premises demanding for regime change.” This act of retaliation against Jammeh’s regime resulted in more arrests, including the arrest of the UDP’s party leader and opposition candidate, Ousainou Darboe.

Catalyzed by the death of Sandeng and the arrest of Darboe, citizens made their voices heard. Exiles from The Gambia in Senegal, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States formed an effective resistance group, composed of eight diverse political parties who united behind Adama Barrow, an unlikely candidate with a background in real estate. With only so many months left until the presidential election, the coalition had to agree on a new candidate quickly.

Analysts attribute Barrow’s successful nomination not only as a result of his platform advocating for human rights, but as a result of the jailing of UDP’s Ousainou Darboe. The coalition used social media to advocate for Barrow, and viral text messages to organize protesters on the streets of Gambia, with Sandeng’s death serving as a key feature in the messages. Collaboration on social media networks by use of hashtags, #JammehMustGo, #GambiaHasDecided, #GambiaDecides, #GambiaRising, and #FreeGambia, along with the power of Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp, allowed for citizens living in The Gambia, as well as those in the diaspora, to collaborate.

A Peaceful Transfer of Power

On December 1, 2016, by way of a marble voting system, Gambians rejoiced upon hearing that populist opposition candidate, Barrow had won with 45% of the vote. Two weeks later, Jammeh rejected the results and attempted to rerun the election, intent on living out his proclaimed “billion-year rule.” The Gambia seemed to be heading toward civil war. During the time spanning from December 2016 to January 2017, an estimated 45,000 Gambians fled to neighboring Senegal and Guinea, including President-elect Barrow. The political establishment surrounding Jammeh began to crumble. Government figures deserted their posts, such as the head of Gambia’s Electoral Commission Alieu Momar Njai, who went into hiding after announcing the results of the election; the Chief Justice of The Gambia’s Supreme Court refused to hear Jammeh’s case challenging election results. The once powerful ruler started to look weak even among his most loyal followers, as he lacked political, economic, and regional backing.

A Template for Democratic Transition?

The advancement of democratic ideals in West Africa allowed for neighboring nations and international players to act in unison against Jammeh. The United Nations, the African Union, and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) expressed that they would not recognize Jammeh after his rule expired on January 19, 2017 , a threat Jammeh took seriously, given ECOWAS’ growing military strength and proven success in democratization efforts in Guinea, Niger, Togo, Ghana, Senegal, and Nigeria. The member nations also allowed for Barrow to take his oath of office at the Gambian Embassy in Senegal. ECOWAS mobilized 7,000 troops from Senegal, Nigeria, Ghana, and Niger in an effort to prevent violence and maintain civilian safety in the time before Barrow’s inauguration. No blood was shed during these few weeks.

The intervention of external powers serves as a model for democratic engagement in the region. Jammeh’s polarizing unpopularity compelled outside observers to unify behind Barrow’s candidacy and discredit Jammeh, while the proliferation of ECOWAS’ democratic institutions allowed for West African countries to work together. According to Nic Cheeseman, a professor of democracy and international development at the University of Birmingham, “[West African countries] like to demonstrate their democratic credential by pushing democracy in the region.” The growing network of democratic states in West Africa could be the key to the beginning of a more stable region. It is the responsibility of international actors to ensure peace and effective democracy in the area through economic and humanitarian support. Many will argue that American interests lie in its own domestic issues and that Africa provides scarcely any economic incentive for America to intervene. However, improving security and good governance on the continent will help to foster a more stable world, complete with strong international alliances, prosperous economies, and a universal respect for human rights, which will hopefully pave the way for international cooperation in times of global crisis.

The question remains whether or not this type of intervention could work in other countries on the continent. In the Global Peace Index 2018 report, four out of the five countries with the largest improvements of peace were in sub-Saharan Africa, with Gambia taking the lead, followed by Liberia. However, the report notes that even though there are many improvements on the African continent, there is an ever-widening gap between most free and least free countries. Countries like South Sudan, Ethiopia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) have been subject to increased violence. The DRC and Cameroon will be holding elections in September and December, respectively. Both countries will be in similar situations to The Gambia, seeking change after decades of dictatorship and political instability. Regional and international actors should play an active role in ensuring the continuing trend of peaceful transition of power on the continent.

The collaboration of West African states and international actors in the crisis in The Gambia allowed for the removal of a maligned leader whose actions dissolved a longstanding democratic constitution; banned political parties; tortured, arrested, and killed those who spoke out against the government; and sent the country to near economic collapse. Since Barrow started his five year term, exiled journalists and activists have returned, political prisoners have been released, and democratic initiatives have been put into place, including the launch of a full-scale inquiry into Jammeh’s use of state funds. Ousainou Darboe has been released from prison and named Vice President, and in June 2018, eleven members of the Constitutional Review Commission were sworn in to review and amend the 1997 Constitution in order to, “redress the wrongs and come up with a Constitution that will stand the test of time.” A peaceful transition of power and a 21-point increase in freedom in The Gambia were made possible due to the power of social networks and the alliance of regional and international actors.

About the author:

*Laura D’Aiello is an intern at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. She is a senior at Temple University majoring in Communication Studies and French.

Source:

This article was published by FPRI.