Australia As A Middle Power: Fighting Or Fanning The Flames Of Asia? – Analysis

By FRIDE

By Andrew Carr*

Every year, Australians face the peril of bushfires. For those whose houses might be at risk, there is always a difficult choice: Do you volunteer and work with relevant institutions to collectively help pre-empt any outbreaks in your area? Do you find like-minded friends and partners and fight to protect your own house and community? Or do you take your family away to safety and hope for

the best?

Asia’s strategic system has not yet produced flames, but there is plenty of smoke and similar dilemmas for policymakers. Australia’s conservative ‘Coalition’ government firmly believes that the best approach is to work with likeminded partners such as the United States (US) and Japan. Indeed the former Prime Minister Tony Abbott (2013-2015), himself a volunteer firefighter, undertook this task with a sense of urgency, in the growing belief a fire has already been lit.

The opposition Australian Labor Party (ALP), currently led by Bill Shorten is much less confident in its approach. By nature the party prefers collective, preventative responses. The ALP has a long record supporting existing institutions and promoting new ones. For example, an unsuccessful 2008 bid for an ‘Asia-Pacific Community’ to address precisely these issues. Yet the party also recognises this may not be enough. Lacking clear ideas for how to revive global multilateralism, it has also worked to deepen the Australia-US alliance.

While no major public leader has called for Australia to abandon the increasing heat in Asia for the cooler climate of the South Pacific, these sentiments can be found in the public. Many Australians are very sceptical about sending military forces beyond Australian shores, and would prefer to concentrate on domestic issues rather than foreign entanglements. How Australia chooses between these options will do much to shape its actions as a ‘middle power’1, and in the long term may even determine whether it remains one.

AUSTRALIA’S WORLD VIEW

Australia exists because of the creation of a globalised, western-led order. Founded by the British in 1770, the country has always seen its security as intimately tied to international order and stability. It was for this reason Australia sent vast numbers of its young men to fight in Europe and the Middle East in both 20th century World Wars. Australia was also eager to be involved in the resulting League of Nations and United Nations (UN). The Cold War offered the first sustained threat to Australian interests, yet was largely viewed by its government and people in terms of a potential change to global order and the clash of norms and values.

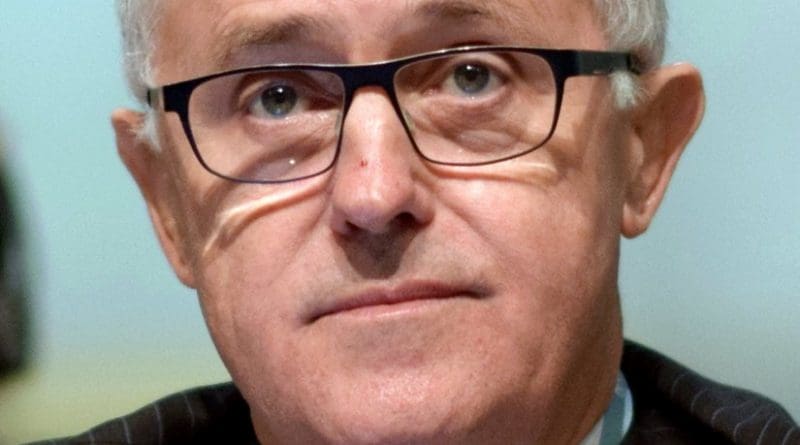

Australian thinking about today’s changing international environment is once more primarily based around values and norms, rather than defending specific national interests. Following British maritime strategist Geoffrey Till, Australia is best seen as a ‘post-modern’ nation, concerned with protecting a globalised, interconnected society.2 Such ideas come naturally to the new Prime Minister, Malcom Turnbull, who took office in September 2015. Turnbull is a former investment banker, who stresses the economic opportunities alongside the dislocation and risks of Asia’s transition. Persuading the public to this view, and explaining Australia’s role will however require new rhetoric. The familiar label ‘middle power’ has over 70 years of use in Australian politics, but is seen by many as carrying too much historic baggage to be of use.

The country merges a sense of short term pride in Australia’s move up the global economic ranks — 12th overall in nominal Gross Domestic Product terms — along with a fear of relative decline in the long term. In a world where population is overtaking productivity as the main determinant of national wealth, Australia’s 23 million people mean a future of declining significance compared to South Korea (50 million), Vietnam (91 million), and Indonesia (249 million) — let alone India (1.29 billion) and China (1.37 billion). This shifting distribution of power, particularly in terms of conferring legitimacy, will make it harder for Australia to remain a middle power in normative and institutional terms, even if it materially remains prosperous and secure. As such, its primary security goal is the preservation of the existing global order, rather than a concern that Australia itself may be attacked or have its interests forcibly threatened.

In the nation’s capital, two widely discussed threats are Islamic State and Russia. Both may harm individual Australians, but almost certainly never Australian territory. Rather, it is the challenge these actors present to the Westphalian and Western-led order that draws Canberra’s attention. China occupies an even greater role in Australian thinking about global order, yet it too is unlikely to directly threaten core Australian interests, let alone the Australian continent.

As such, the debate around modern security issues is largely framed in terms of the stability of the international order, the degree to which its key norms and values remain, the scope for smaller nations to be heard, and how disputes and differences are likely to be resolved in the future. Only in the South Pacific are Australian concerns less abstract and tied to specific interests. This is a region for which Australia bears some responsibility, and where a range of secondary order problems loom. Climate change, for instance, is likely to lead to greater demand for humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. At its worse, it may also provoke political and social instability in some nations, or lead to mass migration.3

Setbacks to the rule of law and a lack of capacity in the small island states of the region may also encourage criminal activity such as drug smuggling. These issues matter and at times draw significant Australian interest. But, save a cataclysmic change, will receive less attention and resources than the strategic issues of Asia or global instability. For all the ongoing debate, Australian foreign and defence policy settings have remained relatively stable.

AUSTRALIA AS A MIDDLE POWER – COOPERATING WITH LIKE-MINDED PARTNERS

The Australian government’s firm belief is that the best response to international and regional instability is to cooperate with larger states of similar attitudes. This is not collective action in the sense of institutional multilateralism. Rather it is more of an informal coalition, bringing together those with similar interests and most importantly similar values. To this end, the current government has strongly re-enforced its ties with the US. It has built on a 2011 agreement, signed under the previous Labor government, to base US Marines in Darwin in the country’s north. Negotiations are underway to base US bombers such as the B-2 and B-52s in Australia as well.

There has also been a strengthening of ties with Japan, as a fellow democracy over previous years. Speculation was rife in 2014 that Japan had agreed to sell 12 diesel submarines to Australia, the largest military transfer in either country’s history. Any such deal may be derailed by domestic pressure over local industry and jobs, but there is a chance it could still come to fruition. Australia, Japan and the US also work together through the Trilateral Security Dialogue, which enables regular meetings of cabinet level officials from Tokyo, Washington and Canberra. Many in this triangle would like to bring in India to create a powerful democratic and capitalist quadrilateral. To support these ambitions the government has recently increased defence spending from 1.56% to 1.93% of GDP. Both parties are now committed to a 2% target as a benchmark.

Though keen to stay close to the US, the Australian position should not be described as a ‘deputy sheriff’. Australia has differed from the US on several issues. It is unwilling to be seen as a launching pad for US flights against China’s interests in the South China Sea. Canberra also signed up to China’s Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) against Washington’s wishes, and has urged a larger role for Beijing in existing forums such as the International Monetary Fund and Asian Development Bank. Finally, while American thinking over the last 18 months has been increasingly framed in terms of regional competition with China, Australian officials resist notions of an inevitable clash.

This is not to presume Australia will have to choose between the US and China. As Nick Bisley of La Trobe University perceptively notes, Australia is not a ‘conflicted ally’. Along with its comfort in the western, US-led global order, ‘Australia’s experiences of China’s increasingly confident and assertive policy in 2009 and 2010 … catalysed policy thinking’.4 The differences between Canberra and Washington are due to slightly different national interests that shape how they interpret and rank the key aspects of the global order. Washington remains unable to separate its leadership role from the order it helped create. Canberra meanwhile would accept greater equality between the major powers if this meant the order remained stable. Where Washington is inclined to view each moment as potentially defining and talks of grand bargains, Canberra prefers a more pragmatic, ground up approach. As the head of Australia’s diplomatic corps, Peter Varghese, has put it ‘The process of adjusting to shifting power balances in a multipolar Asia will be incremental and organic’.5

Australia accepts rather than encourages the expected multipolar order, and has largely welcomed the rise of other powers in Asia. Most notably, it has publicly supported India’s desire for a permanent seat on the UN Security Council, and made peace with New Delhi’s nuclear acquisition, agreeing to sell it uranium in 2013. Such is the pull of India, that Australian strategic policy has been reframed as operating within the ‘Indo-Pacific’ — a region spanning one-third of the world’s surface, covering South Asia, Southeast Asia, Northeast Asia and the United States.6

Australia’s political class has also reconciled itself with a rising Indonesia. Relations have been particularly weak and fractious in recent years due to a rolling series of crises over issues such as the live cattle trade, asylum seekers, Australian drug smugglers and allegations of high level spying on the former Indonesian President and his wife. While distrust and uncertainty remain, Australian defence policy is no longer designed around countering threats from Indonesia, as it had been from the 1960s until well into the 21st century. Today however, Australian officials increasingly look to Indonesia as a long term partner and fire- wall against traditional and non-traditional security problems.

Indonesia might not be willing to reciprocate, presently seeing little value in its smaller southern neighbour. Still, the shift is substantial and any combined efforts from these two middle powers would be significant for the regional order.

AUSTRALIA’S MULTILATERAL OPTIONS

In a bid to pre-empt a clash with emerging powers, or an order transition away from the western-friendly status quo, the Australian government has actively participated in multilateralism to shape and mould the order. This effort has been more understated in recent years than it was in the early 1990s, in part because of a lack of major new ideas or radical re-thinking. This cautious but engaged style also suits the current Australian government and to a degree the regional mood. The former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd had set out to restore Australia’s activist middle power role, but only succeeded in earning a reputation for too much talking and too little listening. Southeast Asia in the early 1990s was also open ground for new forums and bodies to be tried, while today there is a sense of institutional fatigue. There are more meetings than most of the big countries can possibly send senior representatives to, and scholars talk of a ‘noodle bowl’ of acronyms and associations that intertwine, overlap and entangle.

Institutionally, the East Asia Summit (EAS) is now the most important multilateral structure for Australia. This represents a change since 2007, away from the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) which has struggled to move beyond economics. The EAS has the right membership, involving all the major countries of the region, and a clear mandate for addressing regional security and economic concerns. Yet like other institutions its promise has gone unfulfilled in recent years. Some Australians still hold faith in the UN — as evidenced by the bid for a rotating seat on the Security Council for 2013- 2014. But few expect the world body to solve the particular challenges facing Australia’s region, or be the forum for a new global bargain on world order. Australia has regularly encouraged UN reform as a serious project. Yet it has found the path regularly thwarted, and lacks both the authority and necessity to demand change.

The G20 is also invested with promise, especially after Australia was the host nation in 2014. The Brisbane summit committed members to raising GDP growth for members by 2%, and a range of other investment, trade and productivity ambitions.7 Notably one of Australia’s favourite new multilateral structures, MIKTA (Mexico, Indonesia, Korea, Turkey, and Australia) is itself a by-product of the G20s division. With the G7 and BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) often operating as sub groups within the body, the left over middle powers had to fend for themselves. Yet like a firetruck driven by committee, just agreeing on the proper destination is proving difficult.

The rise of MIKTA shows Australia’s willingness to look for new partners. Of course, every politician, scholar and briefing document over the last decade has talked about wanting new and more cooperation. Limits are easily reached, and some common purpose is required for meaningful consultation and cooperation to occur. Australian engagement with the European Union (EU) will therefore likely occur on an ad hoc basis. Canberra is a member of the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) and Asia-Europe Foundation (ASEF). These forums were important openings for responding to the murder of 28 Australians aboard MH17, shot down over Ukraine. Canberra may also be willing to support European initiated policies on refugees, counter-terrorism, internet governance, or, in the right circumstances, climate change. In the vast majority of cases, this will require European initiative to start cooperation. It is not that Australia is unwilling to lead or cooperate with other middle powers. But when it wants to do so, it will, to use the words of the former Prime Minister, lean towards ‘more Jakarta, less Geneva’.8

Canberra continues to assume that the challenge of emerging powers to global order will be evolutionary rather than revolutionary. It regularly reassures itself that given the prosperity and benefits these countries have earned, they will not risk it all. As such, the hope is that by showing a willingness to defend the order, along with making small adjustments to the structure, these countries will moderate their behaviour and become fully incorporated members. On the security and economic front, Australia is unlikely to return to its norm entrepreneurial past when it championed issues such as non-proliferation and trade liberalisation.9 Uncertain times seem to be cowering rather than compelling Australia’s middle power identity, making it more ad hoc and focused on the short term than previously.

FUTURE PROSPECTS – FIGHTING OR FANNING THE FLAMES?

Australia’s real choice is not between the US and China, but between continuing to protect a normative-based global order, or abandoning it for a power-based order. The former is the status quo option, to continue investing in the experiment of multilateralism, laws and norms as a way to manage conflict and clashing interests. In other words, to continue working collectively and hope that will pre-empt any threat from breaking out.

The latter path is to decide that the benefits of the current order cannot be separated from the US (especially US military dominance). This would mean deciding that preserving American primacy is the only real path to safety, and if that requires declaring the rules-based international order unworkable, then so be it. This would be the like- minded coalition option, working with a select, trusted few to fan the flames in the hope it burns bright but quickly. It is a more comfortable path today, given the trustworthiness of old friends over institutions.

But it is also potentially more dangerous in the future, requiring Australia to support those same friends should they find themselves in a conflict. Some states in Asia also worry that building new security links will not deter China but re-enforce its fears of containment, thus fanning the flames for a potentially devastating conflict.

A crucial factor in Australia’s future as a middle power will be the role of domestic public opinion. The public has tended to go along with support for the global order, but far less enthusiastically than the policy elites. There are undercurrents of xenophobia and protectionism which also threaten to undermine national deals. During 2014-15, economic deals with China and security arrangements with Japan faced significant public opposition. Supporting the US and the UN remain overwhelmingly popular, though the former more than the latter. While not displaying the same rising nationalism as other parts of the globe, Australian political leaders ignore public opinion at their peril. When Tony Abbott was in opposition he masterfully tapped a torrent of public anger. But as Prime Minister he found himself the target and was washed away by it. After less than two years as leader he was replaced, marking the fourth change of Prime Minister in the last five years. If the public decide to abandon Asia’s great game for the presumed safety of isolation, it will require a rare and brave leader to stop them.

As Australia’s new Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull likes to quote, The Economist magazine once described Australia as ‘one of the best managers of adversity the world has seen and the worst managers of prosperity’.10 Let us hope this is true. This middle power, once condemned to the ‘Tyranny of Distance’ now finds itself facing the ‘Peril of Proximity’. It is on the front lines of the 21st century’s most important geopolitical struggle and will need all the guile and creative diplomacy it can muster to help blow away the

smoke, tamper down any flames and keep the globe safe and cool.

About the author:

*Andrew Carr, Research Fellow, Strategic & Defence Studies Centre, Australian National University

Source:

This article was published by FRIDE as Policy Brief 208 (PDF). This Policy Brief belongs to the FRIDE project ‘The new Asian shapers: Middle powers, regional cooperation and global governance’. We acknowledge the generous support of the Korea Foundation and of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade of the Australian Government.

Endnotes:

1. This FRIDE project defines middle powers as those that can play a

means, while not ranking among the global heavyweights by most

critically important role in regional affairs and beyond through cooperative power indicators.

2. G. Till, Seapower: A Guide for the 21st Century. Third Edition. (New York: Routledge, 2013) pp. 35-41.

3. K.Koser, Environmental Change and Migration: Implications for Australia, Analysis, Lowy Institute for International Policy, Sydney, 2012.

4. N. Bisley, ‘An ally for all the years to come’: why Australia is not a conflicted US ally, Australian Journal of International Affairs, 67(4): 403- 418, 2013. p.413.

5. P. Varghese, ‘An Australian world view: A practitioner’s perspective’, Speech to the Lowy Institute for International Policy, 20 August 2015 http://dfat.gov.au/news/speeches/Pages/an-australian-world-view-a-practitioners-perspective.aspx

6. G. Dobell, ‘Australia’s Indo-Pacific understanding’ The Strategist, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 17 August 2015, http://www.aspistrategist.org.au/australias-indo-pacific-understanding/

7. G20 Leaders’ Communiqué Brisbane Summit, 15-16 November 2014, http://www.g20australia.org/sites/default/files/g20_resources/ library/brisbane_g20_leaders_summit_communique.pdf

8. A. O’Neil, ‘Less Geneva, More Jakarta? Assessing Australia’s Asia Pivot’, The ASAN Forum, Special Forum http://www.theasanforum.org/less- geneva-more-jakarta-assessing-australias-asia-pivot/

9. For a fuller discussion, see A. Carr, Winning the Peace: Australia’s campaigns to change the Asia-Pacific, (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2015).

10. M. Turnbull, ‘Breathing Life Back into Australia’s Reform Era: Launch of Ross Garnaut’s ‘Dog Days’’ National Press Club, Canberra, 15 November 2013. http://www.malcolmturnbull.com.au/media/breathing-life-back-into-australias-reform-era-launch-of-ross-garnauts-dog