Brazil: Sustainable Fashion Born In Favelas

By Tierramerica

By Fabiana Frayssinet

A Brazilian designer has taken fashion from the exclusivity of the catwalk to the reality of the favela, to demonstrate that styles, trends and fads are also born in these poor neighborhoods of cities like Rio de Janeiro.

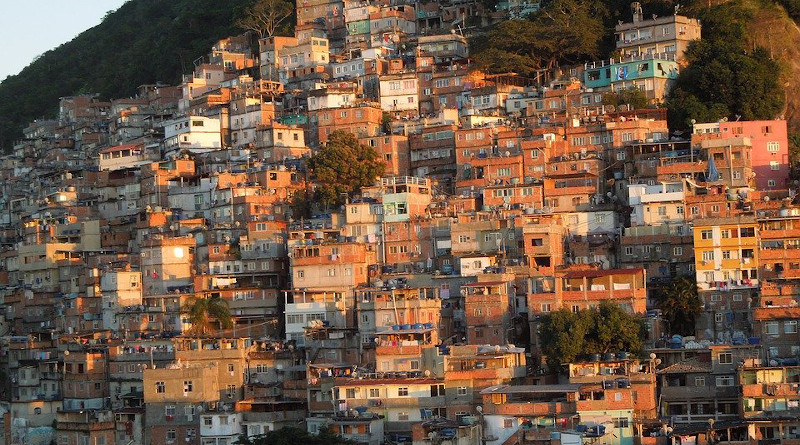

The Mangueira favela or shantytown, home to some 18,000 people, bears no resemblance whatsoever to Milan or Paris.

Once overrun by drug trafficking-related violence, Mangueira is currently undergoing a process of “pacification”– a government strategy combining police repression and social spending. Few of the streets here are paved, most of the houses are unfinished, and the clothing tastes of the female residents run towards very short shorts and skin- tight pants.

“We’re the ones who set trends. Whatever we wear here on the mountain (the steep hillside where the favela is located), a week later, someone is already wearing it out there,” Mangueira resident Vanesa de Oliveira told Tierramérica.

A different type of braid, a shoe style, a stitching detail on a blouse, or some other idea that occurs one day to a woman in the favela: all of it eventually ends up on the other side of the world, or “out there” as Oliveira sees it.

These new trends spread quickly through the city, because “the people up here are very creative. We’re not afraid to be daring; we don’t care about what people will say. If a woman puts something on, looks in the mirror and thinks she looks good, nothing else matters.”

Oliveira’s point of view seems diametrically opposed to that of Fashion Week in Rio de Janeiro. Held during the Southern hemisphere spring, when temperatures soar above 30 degrees, it showcases the colors and textures dictated by the frigid European winter.

“There are various political struggles, and one of them is the construction of our identity. Are we going to use fabrics from other cultures, adapted to other geographical settings and temperatures? What kind of textile industry do we want?” asked Brazilian fashion designer Almir França, in an interview with Tierramérica.

França is seeking the answers to those questions though EcoModa, a project he is coordinating in Mangueira. In the favela that gave birth to the samba school of the same name, one of the highlights of Rio’s annual Carnival, the project currently offers classes in sewing, embroidery, fashion design and modeling to 150 students.

“The idea is to recognize that fashion in Brazil is born on the periphery, in the suburbs,” said França.

“Contrary to the common belief – that fashion is something very elitist, imposed by Paris, created in Europe – fashions and trends in Brazil are actually established by the majority of the population,” he maintained.

We interviewed França at the project headquarters in Mangueira where the courses are being offered, thanks in part to the support of the Ministry of Environment of the State of Rio de Janeiro.

One wall is covered with wallpaper recycled from the dressing rooms of the Mangueira samba school. Hot pink and green, the trademark colors of this Rio Carnival institution, cover another wall brimming with flowers.

The chairs, rescued from garbage dumps, have been revived with fabric remnants recovered from a textile factory.

Oliveira is one of the students in the sewing class. She is using the opportunity to sew a dress for her daughter to wear at a school performance.

Other students are taking classes in embroidery, fashion design and modeling. The common thread running through all the activities is an emphasis on reusing materials and causing the least possible impact on the environment.

The goal is to “get into the students’ heads that it is possible to recycle, that creation does not always have to come from something new, that fashion does not have to be synonymous with consumerism, that transformation is another possibility,” said Vanesa Melo, the administrative director of EcoModa.

The textile industry wastes huge amounts of materials, she told Tierramérica. For example, 20 percent of the fabric used to make a shirt goes unused.

EcoModa works with these cast-offs from the textile industry, with the sequins and feathers left behind from Carnival, even with plastic bottles and glasses.

“The big struggle facing human kind today is survival, and environmental issues are closely linked to this,” said França.

“Our job is to recover everything that has been lost,” commented Melo.

One of those losses is the self-esteem of the women of the favelas, tarnished by the stigma of poverty and violence.

Yet many of the creations worn on the runways by “top models” are crafted on the modest worktables of seamstresses from the favelas.

“Those who truly construct fashion are these seamstresses. That’s why, in the construction of our identity, we are also seeking to create fashion that combines the creative process with environmental awareness and social inclusion,” said França.

The EcoModa course appeared like a “gift from heaven” for Andrea Ferrancini, precisely when she needed a new source of income more than ever. She is especially enthusiastic about the possibility of becoming part of a cooperative, based on the principles of the solidarity economy.

“Ours is a fashion of resistance, of visibility, based on a conception of esthetics as social change,” said França.

EcoModa also seeks to distance itself from the international fashion industry, which uses cheap or even semi-slave labor to lower costs and increase profits.

“In other places people are enslaved or turned into mere cogs in the wheel. We want to make people active participants in the entire process of creating, producing and earning profits,” stressed Ministry of Environment representative Ingrid Geromilich.

“We don’t want to create a green label of solidarity to exploit cheap labor. We want these people to play a leading role in their own story,” she told Tierramérica.

Janice Lima wants to be a part of this process. She currently earns a living from home sales of cosmetics, and is taking the classes because they offer “the opportunity for a profession.”

The women barely lift their heads from their sewing machines, sketches and designs, scissors and scraps of fabric.

Their final creations will be modeled by young women from the favela at a fashion show organized by the police unit involved in the pacification operation in Mangueira. This time, for a change, the catwalk will not be in Paris, Milan or the exclusive beachfront neighborhoods of Rio.