Preconditions For BRIC-Style Growth In Philippines – Analysis

In the postwar and post-Cold War era, the Philippines could have been an economic success story. Yet, the opportunity was missed between the mid-’60s and mid-2010s. In the Duterte era, the country is back on track, but BRIC-style growth is needed to overcome the legacy of past policy mistakes.

In the postwar era, the Philippines was one of the expected economic success stories in Southeast Asia. The country was positioned for rapid growth.

Or so it was thought.

Dreams of economic success, realities of stagnation

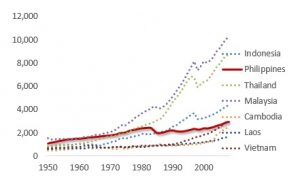

In 1950, Philippine living standards, as reflected by per capita incomes, were only a third lower than in Malaysia, the leading Southeast Asian economy (present-day Singapore excluded). In Indonesia and Thailand, those standards were still 20% behind, while Vietnam and Laos trailed 30% to 40% behind Filipinos.

In the mid-1960s, following the terms of Roxas, Quirino, Magsaysay, Garcia and Macapagal, living standards in the Philippines were only 10% less than in Malaysia, while Thailand still trailed behind, whereas Vietnam had fallen further behind, due to the decolonization struggle against France and the United States.

Despite challenges, the Philippines was catching up with regional leaders until the ‘60s.

When the Marcos era ended in 1986, living standards in Malaysia and Thailand continued to rise. However, Filipino per capita incomes were now 50% lower than in Malaysia and 25% lower than in Thailand; even behind those in Indonesia. Vietnamese living standards had plunged 50% lower than those in the Philippines, but that was due to a devastating war with the U.S.

What followed was a quarter of a century of the People Power Revolution. The assumption was that democratic rule – under Corazon Aquino, Ramos, Estrada, and Arroyo– would spark a dramatic comeback. Yet in 2008, at the eve of the global financial crisis, living standards in Philippines had fallen even further behind Malaysia (-72%), Thailand (-66%) and Indonesia (-34%), even behind Vietnam.

Here’s the irony: When Philippines began its democratic experiment, Vietnam launched Chinese-style economic reforms. The outcome? Philippines stagnated even further, while Vietnam grew in leaps. In some two decades, Vietnam’s GDP almost tripled, whereas that of the Philippines increased only by 50%.

Source: Maddison Database; Difference Group

In the Benigno Aquino III era, Philippine living standards remained more than 70% behind those in Malaysia, 54% behind Thailand and 34% after Indonesia. Despite the rhetoric, the period failed to change the course (Figure 1).

Half a century of missed opportunities

What the Duterte government is now trying to cope with is not just half a century of missed opportunities, but the consequent legacies, particularly corruption.

Here’s one example: Not so long ago, inflation concerns were still fueled by the supply abuses and hoarding of rice and the consequent destabilized prices (rice smuggling soared already in the Benigno Aquino III era). Today, the government must try to contain corruption in the local rice industry, which is one of the goals of the Rice Tariffication Law, while protecting the welfare of local farmers who are struggling with volumes of imported grains.

After the 2016 election triumph, the Duterte government has fought hard to focus on its “Build, Build, Build” investment program, which is what the country has needed ever since World War II. Yet, the implementation has suffered from domestic politics, particularly the (very costly) budget debacle in the spring.

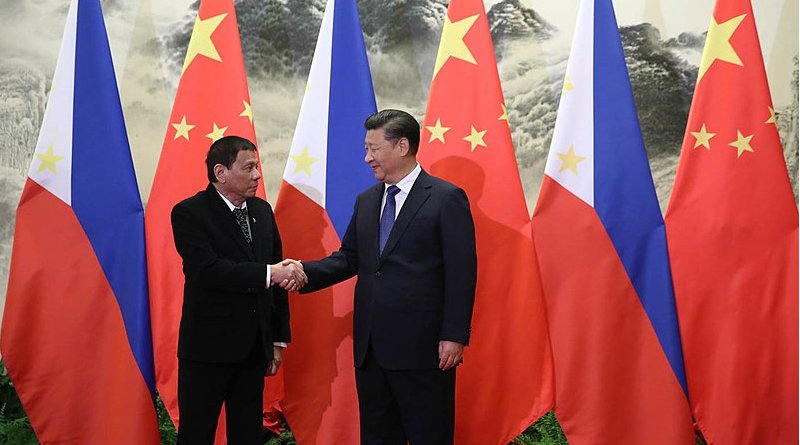

Nevertheless, the government has been able to re-energize Philippine modernization and catch-up growth, thanks to its domestic investment drive and the recalibration of Philippine foreign affairs, which has fueled Chinese investment in the country.

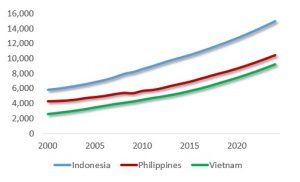

To gain a better understanding of the stakes, let’s compare Goldman Sachs’s original BRIC projections in the 2000s with the actual BRIC prospects today. Assuming peaceful conditions and managed trade tensions, it now seems that between 2000 and 2024, Vietnam would grow fastest (compound annual growth rate at 5.8%), followed by Indonesia (4.2%) and Philippines (4.0%).

If the Duterte government can complete its investment program by 2022 and if the subsequent government will continue to focus on economic development, the country could grow its GDP seven to eightfold by 2025; more than originally projected. Vietnamese living standards would almost quadruple, while those in Indonesia would nearly triple. In the Philippines, living standards would increase 2.5-times (Figure 2).

Preconditions for BRIC-style expansion

Here are some necessary preconditions to achieve Philippine BRIC-like growth in the early 2020s. First, policy mistakes – such as the past budget debacle – are not acceptable anymore. In view of people’s livelihood, such mistakes represent a legally-sanctioned way to penalize living standards in the future.

Second, prosperity cannot be created without stability at home. And the current stability will erode, if the country will face new waves of terrorism, or if economic development fails to accelerate in Mindanao.

A refocused struggle against drugs and corruption should prevail. Even if prosperity can be created, corruption will reduce its benefits. Between 2003 and 2014, the Philippines lost $10 billion in illicit financial flows annually. Tax evasion costs the country $7.4 billion annually; 2.7% of its GDP. Efforts at progressive taxation are elusive as long as the country ranks at par with Haiti and Morocco in tax evasion.

Fourth, as the country moves toward an upper-middle income status, inclusive growth is vital. For decades, exporting people rather than goods and services has been used to offset inadequate job creation. Now BRIC-like growth must increasingly benefit many rather than few – and that means more affordable education, broader welfare and rapid progress in the eradication of poverty.

Prosperity cannot be created without peace and stability in the region. One of President Duterte’s greatest achievements has been his willingness to recalibrate Philippine foreign policy between the U.S. and China. No foreign power should have bases in the Philippines, or rotation arrangements that achieve similar objectives without actual presence. Otherwise Philippines risks being perceived as the proxy of foreign powers that have their own interests in the region.

Sixth, the Philippines needs to further strengthen its economic, political and defense ties with ASEAN nations. Regional mass fosters international bargaining power.

BRIC-style growth is not easy. But when it is successful, it can significantly reduce the weight of past policy mistakes – such as the decades of missed opportunities in the pre-Duterte era.

The original commentary was published by The Manila Times on November 25, 2019