Despite Growing Gender Equality More Women Stay At Home Than Men – Analysis

Women’s labor-force participation rates vary around the globe, and families juggle responsibilities based on policies and work opportunities.

By Joseph Chamie*

Despite noteworthy progress achieved in gender equality, especially in education, employment and politics, women continue to stay at home more than men. Across countries, even among those actively promoting equality of the sexes, the labor force participation rates of women, while substantially higher than in the past, remain below those of men.

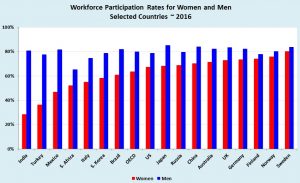

Among the economies examined by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, for example, the average labor participation rates of men and women are 80 and 64 percent, respectively. Large differences between the participation rates of men and women are observed in India, at 52 percent, and Turkey, 41 percent, with 35 percent or less in Mexico and Indonesia. In contrast, small differences in the participation rates of men and women, around 4 percent, are reported in Sweden, Finland and Norway. In between the two extremes are many developed countries with double-digit differences in participation rates of men and women, including Italy, 20 percent; Japan, 17 percent; and the United States, 11 percent.

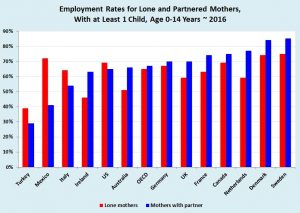

A leading factor influencing gender differences in labor participation involves childbearing and child rearing. By and large, a substantial proportion of mothers withdraw from employment after childbirth. In Germany and the United Kingdom, for example, one in four women leave the labor force following the birth of a child. The impact of parenthood on employment operates in opposite directions for men and women: Employment rates generally decline for women and decline for men.

In addition, childrearing increases levels of part-time work among mothers. In most countries, the incidence of part-time employment is higher for women than men. On average in OECD countries, 26 percent of women and less than 7 percent of men work part-time. Gender differences in time devoted to unpaid care work also impact women’s employment. In every region, according to available data, women spend more than twice as much time than men on housework and family care. In addition to raising children and providing unpaid household work, caregiving responsibilities for elderly, ill or needy family members typically fall on women’s shoulders.

For mothers with young children, the impact of having a partner or being a single parent is mixed. In some countries, such as Mexico, Italy and the United States, lone mothers have higher employment rates than partnered mothers, in others, such as Australia, France, Netherlands and Sweden, partnered mothers have higher rates.

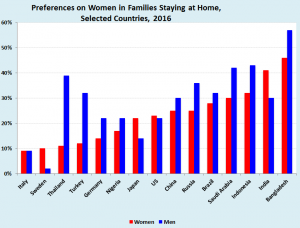

The majority of women and menin every region of the world agree that work outside the home is acceptable for women in families. Globally, the proportions of women and men preferring women to work at paid jobs are 77 and 66 percent, respectively. However, substantial proportions of women and men prefer families with stay-at-home women. Worldwide, more than a quarter of adults – 27 percent of women and 29 percent of men – prefer families with stay-at-home women.

Attitudes about stay-at-home women vary across regions. Countries with relatively high proportions preferring families with stay-at-home women are typically developing countries in South Asia and the Middle East, including Bangladesh and Pakistan. In contrast, low proportions indicating preference for families with stay-at-home women are generally developed countries in Europe, including Denmark, Italy and Sweden. In between are both developing and developed countries such as Brazil, China, Russia and the United States, where about one-quarter of men and women prefer families with stay-at-home women.

Generally, men have higher rates of preference for stay-at-home women, but not always. In Denmark, India, Japan and Sweden, for example, women’s preferences for families with stay-at-home women exceed those of men. Preferences for stay-at-home women also vary by age group. Women and men aged 30 years and over have greater preferences for stay-at-home women than those below age 30.

Again, childbirth and child-rearing are key factors behind such preferences. Practical considerations, including costs of childcare and lack of access to suitable facilities, also play a role. In the United States, for example, childcare can cost more than college. With no government option for care of young children, nearly 60 percent of American parents report that they cannot find reliable, affordable childcare near their homes.

Almost universally, men and women mention a work-family balance as among their top challenges and a reason women stay at home or work part-time. Many, in particular conservative and traditional groups, contend that a stay-at-home mother is essential for family wellbeing, especially for young children. They point to research suggesting long-term benefits for children with stay-at-home parents and challenges for family well-being when mothers work.

Some oppose stay-at-home mothers. French feminist Simone de Beauvoir in 1975 said: “No woman should be authorized to stay at home and raise her children…. Women should not have that choice, precisely because if there is such a choice, too many women will make that one.” More recently, Sarrah Le Marquand, editor-in-chief of the Australian magazine Stellar, wrote that it should be illegal for mothers of school-aged children to stay home and maintains that only when women are expected to work and earn money as men do, with both parents sharing the stress of the “home-work juggle,” will gender equality improve. In addition, stay-at-home women offer untapped potential in the Australian labor force, with considerable gains for the economy if they were employed.

Various reasons are offered for encouraging women to join the formal labor force – including economic independence, self-reliance, retirement preparation and the benefit of female role models, especially for daughters. Families with two incomes are better prepared for unemployment, higher education, martial disruption, illness or economic downturns. Also, recent improvements in the world’s major economies, relatively low unemployment rates and bright prospects for the near term have made it easier for stay-at-home mothers to reenter the labor force, even when they choose to work part-time.

Despite efforts to promote gender equality in occupations and professions, many women still choose to stay at home or work part-time. In the United States, for example, a 2015 Gallup survey found that more than half of women with children under age 18 would prefer to stay at home over working outside the home. Also, nearly 40 percent of women without children under age 18 indicated that they preferred the homemaker role. Available data confirm that women on average spend less and more discontinuous time in the labor force and earn lower wages than men, especially if they have children. Breaks in employment occur frequently following childbirth and generally tend to continue over the early childhood years.

In addition to women having lower labor force participation rates than men, women’s wages remain below those of men. While over the past several decades the gender wage gap has narrowed in nearly all OECD countries, women earn on average 16 percent less than men per hour worked. Gender differences in factors influencing productivity, such as education, potential experience and job tenure, account for little of the gender gap in wages. Gaps are linked to the undervaluation of women’s work and skills needed in female-dominated occupations, discrimination practices as well as career breaks for family responsibilities.

Most women and men around the world no longer subscribe to the proverb “a woman’s place is in the home” and prefer that women pursue paid employment. Substantial gains in women’s labor force participation have been achieved in recent decades with growing support for policies that enable women to remain employed and encourage men to take on a fair share of family care. Also, in recognition of gender inequality in employment, companies have emerged offering programs, guidance and assistance to facilitate the reentry of stay-at-home mothers into the workforce. Nevertheless, gender differences and human reproduction will likely result in more stay-at-home women than men.

*Joseph Chamie is an independent consulting demographer and a former director of the United Nations Population Division.