The United States And The Chaotic Middle East – Analysis

How can the United States safeguard its strategic interests in the Middle East? Gawdat Bahgat believes it needs to 1) give Arab countries the space they need to resolve their internal problems, and 2) pursue closer ties with the region’s three non-Arab ‘peripheries’ – Israel, Turkey and Iran.

By Gawdat Bahgat*

In the aftermath of the Second World War the United States emerged as a superpower with global economic, security, and strategic interests. Meanwhile, the old European colonial powers (mainly Britain and France) gradually saw their prominent status in the international system wane. In the Middle East this key shift in the global balance of power meant that Washington replaced London and Paris as the main foreign power. In the past six decades the United States has been perceived in the region as rival, enemy and/or ally and occasionally a mixture of all.

Interestingly, US goals in the Middle East have been consistent, with little, if any, change. US oil production peaked in the early 1970s, and the United States became increasingly dependent on cheap and secure oil supplies from the Middle East. Private US oil companies have played a major role in oil discovery and exploitation in several Middle Eastern countries, and, at the same time, the United States has been a recipient of billions of petro-dollars of investment. The huge arms deals between Washington and Persian Gulf Arab states in the past several decades have cemented the strategic partnership between the two sides.

The security of Israel and the on-going peace process between the Jewish state and its Arab neighbors have been major US goals in the Middle East. In the past several decades every US administration has spent substantial time, effort, and domestic political capital on the Arab-Israeli conflict and peace process. Secretary of State John Kerry has spent more time working on an Israeli-Palestinian agreement more than on any other issue. These efforts, however, have failed to bridge the huge gap between the two sides’ vision of a peaceful solution.

In addition to these two fundamental goals – cheap and secure oil supplies and Arab-Israeli peace – the United States has pursued other important goals. The 9/11 attacks reinforced counter-terrorism as a main priority of US foreign policy in the Middle East and the rest of the world. Similarly, non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction has been a major US objective for decades. The tension over Iran’s nuclear program in recent years has further underscored the prominence of non-proliferation.

In pursuing these four broad objectives of oil, Arab-Israeli peace, counter-terrorism, and non-proliferation, Washington has relied on key Arab countries, particularly Saudi Arabia and Egypt, as partners. The former is the Arab world’s largest economy and the latter is the region’s most populous country. The United States has different policy and strategy aims with two other major Arab countries, Syria and Iraq. For most of its modern history Syria has been a close ally of the Soviet Union and later Russia. The US occupation of Iraq from 2003 to 2011 is one of the longest wars in the United States history and entailed substantial human and financial costs. Generally, US ties with these major Arab countries have been based more on perceived national interests than on common values.

The three non-Arab Middle Eastern states of Iran, Israel, and Turkey have had unique relations with Washington. Shared Judeo-Christian values are the core of the US-Israeli alliance. Turkey, a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, has long been seen by the United States as a model for other Muslim countries to follow in accommodating Islam with liberal democracy and a free-market economy. Since the 1979 Revolution, Iran has been seen as the main US adversary in the Middle East, accused of sponsoring terrorism and seeking nuclear weapons. The nuclear deal signed in November 2013 between Iran and major global powers, however, represents a potential game-changer in relations between Washington and Tehran. There is no guarantee of success. However, the intense hostility between the two nations is likely to be addressed by diplomatic means than military threats. In short, the recent telephone call between President Barack Obama and President Hassan Rouhani might have started a new chapter in relations between the two nations. Time will tell.

The sweeping security and political upheavals in the Arab world since 2011 and the substantially improved US energy outlook due to technological innovations suggest two opposing US strategies. First, American leadership and active diplomacy is essential. The fighting between Israel and Hamas in Gaza and the on-going civil war in Syria illustrate the high cost of lack of US leadership. On the other side, the recent military gains by Iraqi and Kurdish forces against the Islamic State fighters underscore the difference an active American role can make. Second, the US policy in the Arab world has been proven costly and ineffective. Washington should play a less active role and give major Arab countries the space they need to sort out their domestic and foreign policies and focus on the strong ties it already has with Israel and Turkey and address the major differences is has with Iran. The political values of these three Middle East “peripheries”, Israel, Turkey, and Iran, are closer to US values when compared to other nations in the region.

The United States and the Arab World

Certainly, US policy in the Arab world has varied from country to country and has experienced ups and downs in the past half century. In the past several decades Saudi Arabia and Egypt have been seen as the pillars of US policy in the region, but this is now changing.

For more than seven decades Saudi Arabia has been one of the closest allies the United States has in the Middle East and the Islamic World. Several economic and strategic interests are at stake in this relationship, including oil supplies, Persian Gulf security, and the containment of militant Islam. These mutual interests aside, Washington and Riyadh have recently taken different positions on a number of regional disputes. In recent years the kingdom has exported more oil to China than to the United States. Several US government agencies and members of Congress frequently criticize Saudi record on human rights, particularly religious freedom and the status of women. In February 2011 Saudi leaders strongly expressed their dismay of what they perceived as the US abandoning President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt. Similarly US criticized Saudi military intervention in Bahrain.

Washington and Riyadh also strongly disagree over Syria and Iran. The United States has been concerned over what it perceives as Saudi support to Jihadists and other extremist groups fighting the Bashar Al-Assad regime. On the other hand, the kingdom has strongly urged the Obama administration to take military action against Assad and provide military assistance to the rebels. Finally, Riyadh has little trust in the US-Iran negotiation over Tehran’s nuclear program. Some Saudi officials and analysts have expressed concerns that a US-Iran deal might be at the expense of their country. To sum up, in recent years there has been a growing trust deficit between Washington and Riyadh.

The current status of US relations with another key Arab ally, Egypt, is in a similar state. Unlike Saudi Arabia, which has been a close Western ally since its establishment in 1932, Egypt adopted a pro-Soviet policy after the monarchy was toppled in 1952. The fast toppling of President Mubarak in February 2011 took the United States and many other countries by surprise. After some hesitation, President Obama called on President Mubarak to step down, and the United States pushed for credible and free elections. Washington adopted a businesslike approach toward the Muslim Brotherhood. Since 2013 the Egyptian authorities have ignored US pressure and requests and moved ahead, arresting and charging Muslim Brotherhood leaders, including former president Morsi. The military resents what it perceives as US meddling in Egypt’s domestic affairs. The Muslim Brotherhood, on the other hand, accuses Washington of not exerting enough pressure to prevent or end the military takeover and the toppling of President Morsi. In short, by late 2013 a large number of Egyptian activists, the government, and the Muslim Brotherhood resented the US role.

To sum up, major Arab countries such as Egypt, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Syria, among others, are going through a potentially prolonged period of political and economic instability. Imposing reform from the outside is not likely to succeed; it has not so far. Given the Arab world’s unique culture and history, the Arab people will choose the path and direction of reform, at some stage, but at their own velocity. US efforts to influence or shape the process have largely proven unproductive.

United States and the Peripheries

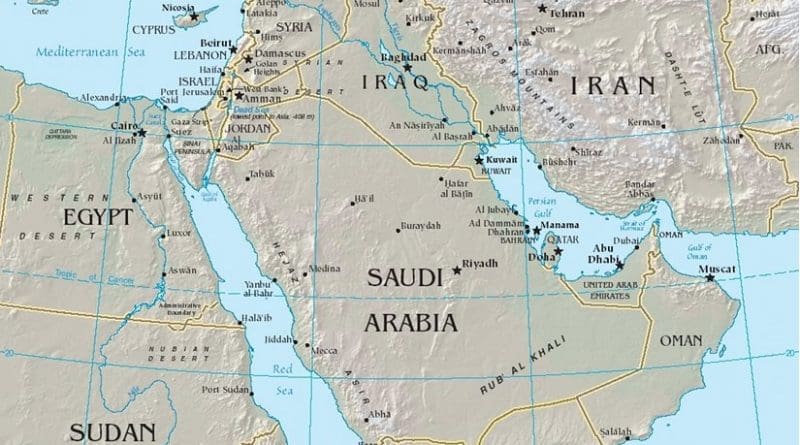

The three non-Arab Middle Eastern countries – Iran, Israel, and Turkey – have historically been called “the peripheries,” because they sit on the edges of the region’s Arab countries, which, with more than 300 million people, undoubtedly represent the heart of the Middle East. US relations with Iran, Israel, and Turkey and the relations between and among these three powers have fundamentally changed in the past several decades.

In the aftermath of the political and security upheavals in the Arab world from early 2011, the regional strategic landscape has fundamentally changed. Rather than Soviet penetration, the current threat is broad socioeconomic and political instability. As regional powers with relatively higher levels of stability than their neighbors, Iran, Israel, and Turkey see both opportunities and challenges in the upheavals on their borders. The United States shares similar sentiments. Washington has traditionally enjoyed close ties with two of the three peripheries, Israel and Turkey. The 1979 Revolution represented a turning point in the relations between the United States and Iran.

After decades of tension between Washington and Tehran, suspicion over Iran’s nuclear program pushed the two countries to the brink of confrontation. The process and outcome of electing President Hassan Rouhani in 2013 has presented an opportunity for rapprochement. Rouhani was considered the most pragmatic candidate and was supported by the majority of moderates and reformers. He also enjoys full support of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. The signing of an interim agreement on the nuclear dispute between Iran and the global powers (the United States, United Kingdom, France, Russia, China, and Germany) in November 2013 potentially could start a new chapter in the relations between Tehran and Washington.

The Way Forward

The on-going political and economic turmoil in several major Arab countries has highlighted the dilemma the United States and other countries face in the broader region. A policy driven by perceived national interests with less attention to transparency and democratic values has proven ineffective and costly. In most Arab countries, both governments and their opponents reject foreign intervention. Indeed, less foreign intervention by the United States and other powers is likely to help Arab countries to determine their future without blaming foreign powers.

Meanwhile, the three peripheries of Iran, Israel, and Turkey enjoy a higher level of political and economic stability than most of their neighbors. In addition to maintaining good relations with Israel and Turkey, the United States can take the opportunity to reduce tension with Iran and help it to be reacclimatized and reintegrated into the regional and global systems. Good US relations with the three peripheries should not be seen as coming at the expense of the heart of the Middle East, the Arab world. The zero-sum policy and mentality should be replaced by a win-win approach.

*Dr. Gawdat Bahgat is professor of National Security Affairs at the National Defense University’s Near East South Asia Center for Strategic Study. He is an Egyptian-born specialist in Middle Eastern policy, particularly Egypt, Iran, and the Gulf region. His areas of expertise include energy security, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, counter-terrorism, Arab-Israeli conflict, North Africa, and American foreign policy in the Middle East.