Climate Change Not All Pain And Expected To Improve Precipitation In India – Analysis

By IPCS

By Sanjeev Ahluwalia

Heat will destroy genetic diversity and trigger migration to cooler climes, water scarcity will constrain food crops, warmer and more acidic seas will denude coral reefs and marine food resources and sea level rise will submerge low islands and coastal areas.

Climate change seems inevitable. Risk takers who go long on property should check out locations in Canada, Siberia and Greenland. These hitherto frozen places are expected to become attractive relocation favourites in a rapidly warming world.

The international institutional architecture for concerted effort has been negligent in protecting future generations. The petty mindedness of the “haves”, particularly the United States, has been less than helpful. But it is not easy to make sacrifices today for the common good two generations hence. We Indians, spend our lives risk proofing our families. But even we baulk at collective action.

Nonetheless, both China and India were aligned with international concerns at Paris in 2015. China (10 per cent of world GDP), with aspirations of global leadership, seized the opportunity to showcase their responsiveness and sense of environmental responsibility versus the renegade behaviour of the US (18 per cent of world GDP). India, though not in the same league, with three per cent of the world GDP — per capita carbon dioxide emissions lower than most economies in our income class (lower medium) and with 25 per cent of the world’s 800 million chronically under-nourished people — bravely punched above its weight and pledged a massive programme of renewable energy.

If the science on climate change is right, the world is already warmer by 1ºC above the 1,850-1,900 level by 2011 and has used up two thirds of the envelope (1,900 against an allowable 2,900 gigatonnes of CO2) of cumulative emissions to contain temperature rise to 2ºC. Annual emissions are 36 gigatonnes of which 40 per cent remains in the atmosphere, 30 per cent is absorbed by the sea which warms it and the residual 30 per cent is captured by land and plants. By 2050 we would have used up our CO2 emissions limit.

Thereafter, we will be on track to a temperature rise between 3.7º to 4ºC by 2100. Our actions cannot avoid global warming. But they can mitigate the scale of the increase and the associated suffering. Heat will destroy genetic diversity and trigger migration to cooler climes, water scarcity will constrain food crops, warmer and more acidic seas will denude coral reefs and marine food resources and sea level rise will submerge low islands and coastal areas.

The Paris Agreement 2015 was about containing temperature increase to 2ºC. It was less an agreement and more a voluntary, collective expression of what each country could do. And clearly that was not enough. Seeking a more rigid agreement would have meant having no agreement at all. Envirocrats abhor not tabling some results. So instead of less CO2 we were sold plans and forecasts.

At the heart of the matter is the trade-off between retaining developed economy consumption standards and in the poor economies, growth prospects versus sustainability. But in a fractious world order today no great power exists which has the capacity or the incentive to mitigate the pain of others. The US is looking inwards, Europe and Japan are ageing and China is still only an upper-middle income country although with cash to spare.

Globally, 40 per cent of emissions are on account of petro-based transportation and coal-based electricity generation. Electric cars, buses and trucks and the charging infrastructure to match might become commercially available by 2030-2040. It will not be a day sooner.

The sustainability objective is to reduce emissions by 45 per cent by 2030 and to zero emission levels by 2050. Emission reduction at this scale would require the complete abandonment of coal-based electricity generation by 2050. That prospect is scary for countries, like India, where the coal economy provides relatively better paid employment concentrated in eastern India. Large swathes of population still live in darkness without electricity — and not just in the far-flung rural areas.

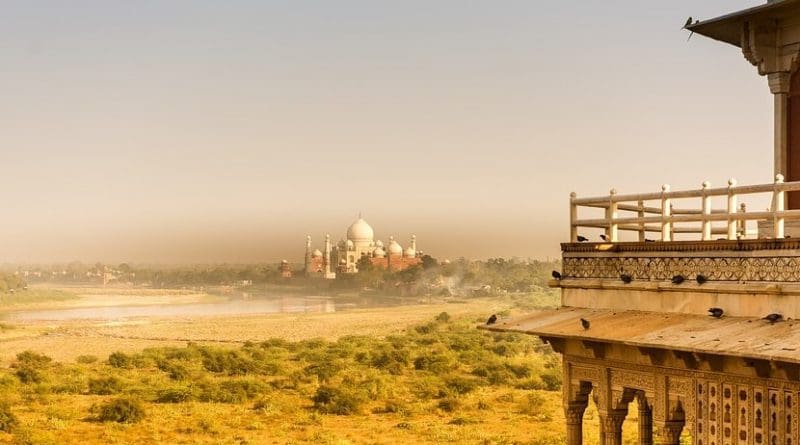

Climate change is not all pain. It is expected to improve precipitation in India by three to 12 per cent. But this comes at the cost of less water in snow-fed Himalayan rivers. Sanjeev Sanyal — a government economist — stresses that adaptation is the key to survival. Mitigation is a humungous task with uncertain results from collective action by sovereigns. Don’t forget African growth is yet to take off and India itself has not plateaued. What then are the likely drivers of success?

First, ensuring sustainability is a classic public good because private actions can never monetise the positive spillovers of their effort and private polluters have no incentives to become responsible without strict regulation. This means the government must view public allocations and tax incentives through the sustainability lens. Consider that the plan to grow bio-fuels is a big no-no. It will strain land and water resources which should instead be allocated to food or forests. Denuded forests must be revived and the decentralised greening of all habitats pursued with vigour.

Second, industrial scale carbon capture and storage (CCS) is an innovative approach for coal-dominated economies. Currently India is peripheral to the CCS technology dialogue, where the US, Canada and Norway lead. China’s first CCS unit will be operational by 2020. The global target is to capture three per cent of annual CO2 emissions (two gigatonnes) by 2020 and seven per cent (seven gigatonnes) by 2050.

Third, India missed the bus on manufacturing solar cells and panels. But manufacturing efficient storage batteries is the new frontier we cannot ignore for harnessing the full economic benefits from scaling up solar energy.

Fourth, decentralising the emissions control programme can tap into local cultural practices which promote sustainability. Frugal innovation in water catchment, storage and management and renewable energy generation and use must be incentivised to create green, local employment and benign outcomes. Genetic engineering of crops to make them drought resistant can protect farmer income, enhance productivity and free up land for water storage and enlarging forest cover.

Multiple objectives are the bane of all government programmes. But sustainable growth should be at the top of this long list.

This article originally appeared in The Asian Age.