Pakistan: The Sharifs Pick A New Sheriff And Nemesis – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

By Sushant Sareen

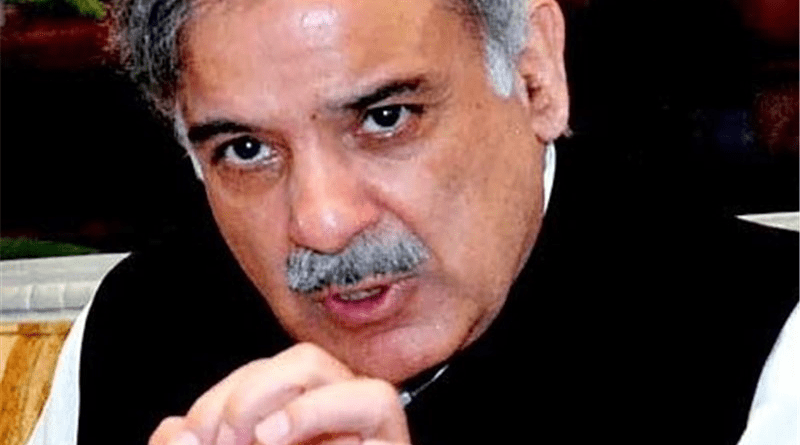

After months of speculation, intrigues, controversies, confabulations, lobbying, and politicking to pressure or influence, Pakistan’s Information Minister Marriyum Aurangzeb announced that Lt. Gen. Asim Munir would succeed Gen Qamar Javed Bajwa as the next Chief of Army Staff (COAS) of the Pakistan Army. Every three years, Pakistan is preoccupied with the guessing game of who will be the next army chief. This is hardly surprising considering the fact that the Pakistan army chief is the de facto ruler of the country. He might be appointed by the Prime Minister of Pakistan, but once appointed, he becomes the Prime Minister’s equal, if not his boss, and eventually his nemesis.

But this year has been quite extraordinary. For weeks, neither catastrophic floods nor an economic meltdown, and not even the resurgence of Islamist Taliban terror attacks has been able to shake the attention of the political class, the media or the public on who will be the sheriff. The entire politics of the country seemed to revolve around this one appointment. In fact, since October 2021, when the fracas over the appointment of the ISI chief tore apart the ‘one-page’ narrative of the Imran Khan government, the question of who will command the sixth largest army in the world has occupied the mind-space of Pakistanis.

Setback for Imran

In March, a no-confidence vote was moved against Prime Minister Imran Khan. Among other things, this was done to forestall the possibility of Imran announcing Gen Bajwa’s successor nearly six months in advance. It was feared that if Imran got his way, the former ISI chief Lt. Gen. Faiz Hameed would be appointed the next army chief. With Faiz backing him, Imran would get rid of all his political opponents and challengers. Winning the next general election would then be a cakewalk for Imran because there would be virtually no one to oppose him.

But the successful no-confidence vote foiled those plans. Even so, since his ouster, Imran took to the streets. He mounted immense pressure to not only force an early general election (which he hopes to sweep) but also to make sure that he has a say in the selection of the next army chief. Imran feared that the Sharifs would pick someone who would go after him with the same vengeance that Imran planned to go after his opponents. In the end, Imran neither got an early election (not so far anyway) nor has he managed to prevent his bête noire, Asim Munir, from succeeding the incumbent COAS.

Pavlovian selection

In a way, Asim Munir’s selection by the Sharifs, in particular former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, was decided by Imran. The more Imran opposed Munir, the more he became a natural choice for the Sharifs. Had Imran been smart he would have kept his apprehensions about Munir to himself. But he was quite adamant that he didn’t care who became chief as long as Munir didn’t. After that, it was a no-brainer whom the Sharifs would pick. The grapevine in Islamabad was that the military leadership–read Gen Qamar Bajwa–was pushing for a less controversial successor.

Out of the top six generals from whom the next chief would be picked, one (Munir) was not acceptable to Imran and another (Faiz Hameed) was not acceptable to anyone else except Imran. With Imran on the rampage, threatening to question the legitimacy of the new chief the military was keen to avoid any controversy. The top brass, therefore, wanted the government to pick someone from any of the other four contenders—Sahir Shamshad Mirza, Azhar Abbas, Nauman Mehmood, and Mohammad Amir. But Nawaz Sharif dug in his heels and didn’t budge. He refused to accept any of the compromise formulas that his brother and the current Prime Minister proposed to him in London. The way Nawaz Sharif saw it, not only did Asim Munir have a stellar record of service but he was also the senior-most general after Bajwa. The clincher was, of course, the reported bad blood that existed between Imran and Munir.

Nawaz’s wrong choices

Nawaz Sharif, however, has an unenviable record of always picking the wrong general to lead the Pakistan army.. To undercut an overbearing Aslam Beg, Nawaz Sharif picked Asif Nawaz Janjua but within months fell out with him. After Janjua, a compromise was worked out on Abdul Waheed Kakar who forced both Nawaz Sharif and the then President Ghulam Ishaq Khan to resign.

Nawaz Sharif’s next pick was Pervez Musharraf, a Mohajir who Nawaz thought wouldn’t rebel against a popular Punjabi Prime minister. But Musharraf did a coup and imprisoned and then exiled Nawaz Sharif. Raheel Sharif was next but relations between him and Nawaz became extremely tense within months of his appointment. The next man was Bajwa who was sold as a democracy-loving general who as Corps Commander was deadly opposed to any military intervention. But Bajwa adopted ‘Project Imran’—a term used for the military establishment’s plan to project Imran Khan as the knight in shining armour, the man who would fix Pakistan.

It was under Bajwa’s watch that Nawaz Sharif was ousted in a judicial coup and was later imprisoned on charges of corruption. Now Nawaz Sharif has picked Asim Munir, and the reason is the old principle,“the enemy’s enemy is a friend”. But is he?

Imran’s Bête Noire

Asim Munir was very much part and parcel of Project Imran. As head of the Military Intelligence and later the ISI, Munir was an integral part of the cabal of generals who was rooting for Imran as the Pakistan Army’s choice for PM. He fell out with Imran, most probably, because he was a genuine acolyte who believed that Imran was a decent and honourable leader. Munir considered it his duty to inform Imran of the corruption that was happening under his nose and in his house by his Pinki Pirni wife and her family (former husband and children) and her cronies (the infamous Farah Gogi who was believed to be raking in money through transfers and postings in Punjab province).

Imran, however, took umbrage at this corruption being pointed out to him and had Munir removed as ISI chief and replaced him with his favourite general–Faiz Hameed. Later, it is believed that Imran tried to besmirch Munir’s reputation by getting people to file corruption and extortion complaints against him. Of course, now Imran will have to make a difficult choice of whether to target Munir or make peace with him. The fact that Munir is here to stay for three years–maybe five more after his first tenure–means that Imran doesn’t have too many options if he wants to get back into power unless, of course, he believes that he can get into a headlong confrontation with the army and still win.

The inevitable conflict

But the important thing is that while there is no love lost between Munir and Imran, it is also not the case that Munir is enamoured of or beholden to the Sharifs. Eventually, Munir and his men will be dragged into Pakistan’s murky politics, if not by the government, then by the Opposition, or even its own interests. That is simply inevitable, even if he wants to avoid it. The Sharifs will certainly look to him and expect him to return the favour by fixing Imran, or at least back them when they make the move to fix Imran. They will also seek some support from the military in the next elections and in the general management of what is an increasingly ungovernable country with huge political, economic, diplomatic and security challenges.

For example, will the Army be okay with a big cut in its budget to help the government reduce the yawning fiscal deficit? Will the Army accept the civilian government indulging in fiscal profligacy to win the next election even as it slashes the military budget? Will the Army allow the civilian government to take the lead in formulating policy on India or Afghanistan? Asides from big policy issues, there are the mundane, everyday things. For instance, Munir will be expected to use the military’s influence and strength to rein in the judiciary and perhaps help in paving the way for Nawaz Sharif to return home without having to go to prison. Simply put, it is a matter of time before tensions erupt between the new army chief and Sharif’s government. A civil-military conflict or, if you will, a clash between the prime minister and the army chief is inbuilt into the Pakistani political system because of the disconnect between de jure and de facto power wielded by the civilian and military leaders. This dynamic will invariably come into play regardless of who is made army chief.

Generals can’t divorce politics

In his parting speech, Gen Qamar Bajwa spoke about how the Pakistan Army had decided to stop all interference in politics. But Bajwa’s epiphany has come when he is on the way out. Disassociating Pakistan Army from politics is easier said than done. No general is or can be apolitical and the entire political structure has evolved in a way that the army is now an integral part of the political system.

Every time the army’s image becomes mud in public perception, it beats a tactical retreat. But even as it does so, it continues to pull strings from behind the scenes, until it is ready to once again come out and play in the open. There is as yet nothing to suggest that this dynamic is going to change with the handing over of the Malacca cane from Bajwa to Munir. As the new chief, Munir will set his own priorities and policies, many of which will be at variance with what Bajwa said at the Martyrs Day ceremony. Not only will there be pressure from the politicians to intercede in politics, but there will also be pressure from within the army to play a role in the affairs of the state. Add to this the international dimension where foreign interlocutors would rather talk to and seek guarantees from the military than from the civilians.

Wait and watch in India

Much like Pakistan, India too will be in a wait-and-watch mode. India has some experience in dealing with Munir when he was ISI chief. During the Pulwama crisis, there are reports of communications between the Indian establishment and Munir. Whether or not Munir will try to seek a détente with India and open a back channel of the sorts that reportedly existed between Bajwa and India remains to be seen. It is quite possible that Munir will avoid any hostilities with India and will focus on Pakistan’s internal and existential problems. After all, it doesn’t make sense for Pakistan to indulge in opening up the Indian front at a time when the Afghanistan front is heating up and Pakistan’s economy is drowning. But there is also a possibility that the new Pakistan army chief will try to do something to convey to India that Pakistan remains in the fray and shouldn’t be taken for a pushover because of the multiple crises it is confronting and contending.

At the political level, it isn’t clear if Munir will support, even nudge, or at least not hinder and obstruct, the government from opening up channels of communication with India and take some steps towards a modicum of normalisation in bilateral relations. The answers will come within a couple of weeks in terms of overtures (if any) to India, the continuation of the ceasefire along the Line of Control, the trajectory of export of terrorism, the revival or at least relief given to Jihadist terror outfits, and the appointments Munir makes in the army.