Abe’s Pacific Rim Diplomacy (Part II) – Analysis

Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo started the year 2017 with his foreign policy activism by undertaking a six-day tour to four Asia-Pacific nations –the Philippines, Australia, Indonesia and Vietnam in January 2017. This article is the second part of a series. To read the first part, click here.

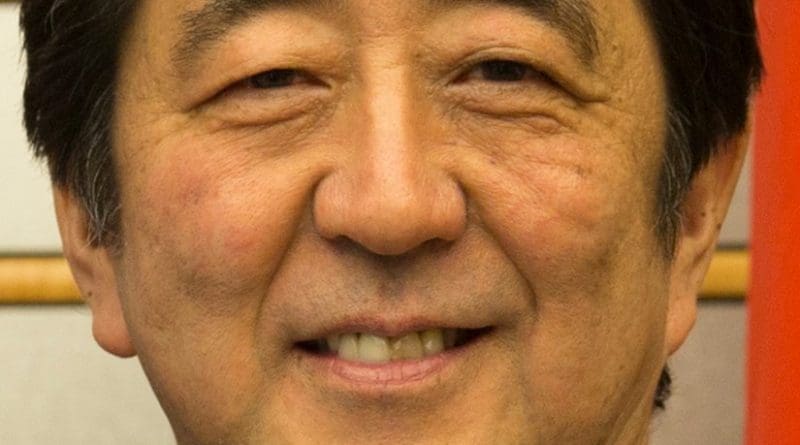

Abe and Joko Widodo

Indonesia was the third stop of Abe’s four-nation Pacific swing. Like in Australia and the Philippines, maritime security issue dominated Abe’s discussion with the Indonesian President Joko Widodo. Both the leaders agreed to boost coordination on maritime security amid tension over China’s military build-up in disputed waters of the South China Sea. Besides, Abe extended Japan’s cooperation in developing infrastructure, including a new port in eastern Jakarta.

How is Indonesia important for Japan in its foreign policy calculus? Indonesia is the world’s fourth-largest population with high economic potential. It is a major power in the 10-member ASEAN grouping and Japan expects that Indonesia shall play a leading role in addressing regional challenges such as the South China Sea. As is well-known, territorial disputes in the South China Sea involve China and five other governments – Brunei Darussalam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam and Taiwan. Neither Japan nor Indonesia is a claimant in the dispute. But both are worried about China’s increasing military presence in the busy shipping lane and therefore want that rule-based order in the sea is maintained for larger interest of global maritime commerce. China claims almost the entire South China Sea, through which about $5 trillion worth of trade passes each year. Japan has a separate dispute with China over the Japanese-controlled Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea, which China calls Diaoyu and Taiwan calls Tiaoyutai.

It was therefore Abe and Jokowi Widodo agreed to strengthen maritime cooperation with regard to the Indonesian navy’s patrolling of the vicinity of the Natuna Islands on the southern edge of the South China Sea. Chinese fishing boats operate illegally in Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone and therefore needs its naval capability to be enhanced to stop such illegal fishing activities. On the one hand China recognises Indonesia’s sovereignty over the Natuna Islands. At the same time it argues that both China and Indonesia have overlapping claims for maritime rights and interest in the area that need to be resolved. Indonesia rejects such assertion. It appears China wants to create a new conflict when there is none.

The Natuna Islands area is also believed to be endowed with oil and gas deposits. Therefore Indonesia proposed Japan to cooperate in exploration activities to achieve three objectives: to make an economically viable project, deter the Chinese presence at the same time, and protect its fishing zone within its exclusive economic zone. Abe expressed Japan’s willingness to support the development of remote islands in Indonesia and the strengthening of the country’s coastal patrol capability.

Infrastructure development is another area closely connected with any program for economic development in any country. Both the leader, therefore, discussed a medium-speed railway project linking Indonesia’s two largest business hubs of Jakarta and Surabaya. The project is part of efforts to revitalise the existing 725-km railway between Jakarta and Surabaya, after Japan lost out to China in September 2015 in bidding to construct a high-speed railway between Indonesia’s capital and West Java provincial capital Bandung.

Besides committing to maritime security, both leaders also affirmed security ties in light of an agreement to seek a pact on the transfer of Japanese defence equipment and technology. Acknowledging the growing threat of Islamic extremism, both sought ways to cooperate on counterterrorism measures. Other areas of cooperation included a yen loan of 73.9 billion yen ($646 million) to help finance port development, irrigation facility construction and beach protection projects in West Java. Discussion on starting a two-plus-two consultative meeting involving two countries’ foreign and defence ministers were also in the menu, which is to commence by the end of 2017.

Japanese investment in Indonesia has also seen significant increase, doubling to $4.5 billion in January-September 2016. The agreements on joint development of the Patimban deep-sea port and the Masela gas field with Japanese involvement are noteworthy. Indonesia has also some other wish-list for Japan to consider: open access for Indonesian agricultural goods, improved access for Indonesian nurses to work in Japan, a review of the Indonesian-Japan economic partnership agreement by 2017-end, and grant national carrier Garuda rights for a Jakarta-Tokyo-Los Angeles route. Thus, the menu in the list is long, which throw up scope for further close cooperation.

Thus it transpires that Abe’s swing through Asia that included two of America’s main allies in the region – Australia and the Philippines – despite Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte’s open hostility to the US during the Obama administration, can be seen as Abe’s willingness to take a leadership role in promoting regional cooperation in the region to counter Beijing at a time when tension is heightened between China and the US during the Trump era amid uncertainty about policies of the Trump administration.

Abe and Nguyen Xuan Phuc

Vietnam was the last stop in Abe’s trip to the Pacific Rim nations. Like in the preceding three nations, maritime security cooperation was at the core during Abe’s discussion with his Vietnam counterpart Nguyen Xuan Phuc. The former US President Obama had started cultivating stronger ties with Vietnam to make it a part of his pivot to Asia policy and even visited Vietnam to get the country on board. Abe’s policy towards Vietnam was in similar direction.

With a view to boost maritime security, Abe offered Vietnam to provide new patrol ships to boost its maritime security capabilities. Through such assistance, Japan aims to support Vietnam against China, whose advance in the South China Sea is a matter of concern that needs to be checked. This was the fourth time that both Abe and Phuc met to confirm a policy of joining forces for stability in the South China Sea. Being the chair of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation in 2017, Vietnam enjoys a special position for Japan for joining forces on the common cause. In addition, Abe announced financial aid aimed at supporting large-scale projects to improve Vietnam’s infrastructure, such as sewage and electricity systems and also for the development of the Hoa Lac high-tech park on the outskirts of Hanoi.

Japan is one of Vietnam’s top investors and trading partners, besides being the single largest bilateral donor. Though both are locked in separate maritime disputes with China, Japan has already provided Vietnam with six used patrol vessels to help strengthen maritime capability and now agreed to provide some more new ones as a part of a fresh yen loan offer totalling 120 billion yen. In 2016, Vietnam withdrew contracts to build nuclear power reactors with Japanese assistance. It was a blow to the Abe government, which views the export of infrastructure as a pillar of his economic growth strategy. This time around, Abe seems to have succeeded to bring back Vietnam on board in his economic growth strategy through other collaborative projects using Japanese capital and technology.

Both Japan and Vietnam are concerned that the US under Trump is shifting gear towards a protectionist trade policy, including the withdrawal from the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP). With the TPP’s future now uncertain, both Abe and Phuc discussed about promoting trade through the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) to which both are members. Unlike the TPP, the RCEP is an Asia-Pacific mega-pact that excludes the US but includes China.

President Trump has already signed the executive order to pull the US out of the TPP. However, the leaders of the rest 11 signatory countries are still trying to salvage the 12-nation trade treaty, if possible, without the US. Vietnam, however, was yet to submit a proposal to ratify the TPP in its National Assembly. That itself remains uncertain now.

Abe’s discussion with the leaders of the four countries – Australia, the Philippines, Indonesia and Vietnam – clearly demonstrated that Japan is really concerned about China’s assertiveness on regional territorial disputes as well as maritime claims on the resource-rich South China Sea. Abe, therefore, stressed in his meeting with leaders in the four countries the level of importance that Japan puts on upholding the law and solving disputes peacefully. Indeed, the issue of South China Sea is no longer confined to the claimant countries but has drawn the attention of the international community as it directly affects the peace in the region and threatens to disrupt global commerce. All efforts, therefore, are to be made to maintain peace and stability to serve every country’s national interests. Maritime security cooperation remains the key for fellow maritime nations.

The author is ICCR India Chair Visiting Professor at Reitaku University, JAPAN.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal and do not represent either of the ICCR or the Government of India.