Next Debt Crisis Could Affect Emerging Market Corporate Sector – Analysis

Emerging markets enjoyed cheap loans since 2008, but now confront rising interest rates and a struggle to refinance.

By Anthony Rowley*

There are disturbing signs that yet another international debt crisis could be brewing, given the toxic mix of huge debt, built up over a decade of record low interest rates, and the fact that rates have begun rising again now. This comes less than a decade after the global financial crisis of 2008.

International debt crises increased in frequency and intensity in recent decades, from the Latin American debt crisis of 1982 to the Asian financial crisis of 1997 and the global financial crisis of 2008. Each is said to be the “crisis to end all crises” with governments making some perfunctory fixes, until the next one came along.

What’s different this time is that, rather than being a sovereign debt crisis or a crisis for the banking and financial system, the epicenter of the eruption now could be in the emerging market corporate sector.

Global debt has reached $217 trillion, equal to a record 325 percent of global gross domestic product with buildup being particularly marked among business corporations in the world’s leading emerging economies as well as among some governments in mature economies.

“The sheer size of global debt raises the risk of unprecedented [debt] deleveraging that could hamper growth worldwide,” notes the International Monetary Fund. The sentiment is echoed by Tim Adams, head of the Institute of International Finance in Washington. The institute has almost 500 members including banks and insurance firms that promote sound practices and regulatory policies, global financial stability, and sustainable economic growth.

In absolute money terms, debt is largest in advanced or “mature” economies where total debt across the household, central government, financial and non-financial corporate sectors has reached $165 trillion or 390 percent of GDP with government debt rising especially sharply.

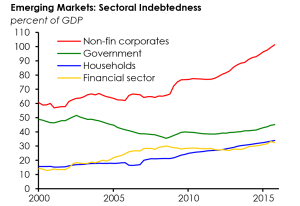

Total emerging market debt is around $53 trillion or 217 percent of GDP with nearly a half of this, or $25 trillion, concentrated in the non-financial corporate sector rather than banks and other financial institutions.

According to the Institute of International Finance, the highest ratios of non-financial sector corporate debt to GDP among emerging markets are seen in Hong Kong, China, Singapore, Thailand, Chile, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Indonesia, Mexico. Malaysia, the Czech Republic and South Korea.

High levels of debt do not in themselves indicate an impending crisis. But when a dramatic surge in borrowing is followed by a sudden, and almost certainly sustained, rise in interest rates, the cost of servicing debt threatens to outrun the ability of borrowers to repay.

The crisis building now is not really like past crises. It is very much a “monetary” phenomenon where borrowers have succumbed to the lure of ultra-cheap, even “free,” credit made available in vast and unprecedented quantities, courtesy of the world’s leading central banks.

The so-called “Great Recession” which followed the global financial crisis after 2008 was prevented from developing into a Great Depression by a massive official bailout of mainly US financial institutions, with only Lehman Brothers directly “going to the wall.”

The bailout funds were supplied largely by central banks, notably the US Federal Reserve. But it was really the follow-up action of these central banks – in particular the Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank and the Bank of England – that sparked the big debt buildup.

Under quantitative and qualitative easing programs, central banks bought trillions of dollars’ worth of financial assets from governments and from the private sector to drive down the cost of money, and so avert bankruptcies, repair balance sheets and restore credit creation.

This strategy meant that a potential Great Depression became instead a Great Moderation in economic growth. But there was a dark side to the massive bailout, and that dark side is threatening to emerge in the shape of a new emerging market debt crisis that could expand into a global crisis.

Not only did credit become historically cheap, in “real” or inflation-adjusted as well as nominal terms, but capital also began to be re-routed globally. Funds fled from the US where yields on government bonds and Treasury Bills fell to derisory low levels under the impact of the Fed’s quantitative and qualitative easing assaults. The “hunt for yield” was on, and yield was to be had especially in emerging markets.

Emerging market companies not surprisingly took advantage of this situation, and many borrowed up to the hilt. Not only that, some have borrowed in dollars while their revenues are in local currencies – creating a classic “currency mismatch” situation.

Global investors have been eager to snap up corporate bonds issued by emerging market companies during the era of low, zero and even in some cases negative interest rates – this despite the fact that credit ratings were often very low and risk premiums very narrow on such bonds.

Corporate borrowers in Brazil, South Korea, Thailand and other emerging markets especially have been big borrowers. While most of this has been in local currencies, corporates in India, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Russia as well as Hong Kong and Singapore have borrowed heavily in foreign currency.

How could this turn into a new crisis? Companies need to renew or roll over their debts, and if banks raise lending rates or even deny fresh loans, some borrowers will be in trouble. The same is true if bond market borrowing rates rise or credit dries up.

An ominous sign in this regard is that, as the IIF has noted, the “with higher global interest rates, emerging market corporates with large refinancing needs could face headwinds” – and a lot of refinancing is coming due in 2017.

Downgrading of credit ratings accelerated rapidly in 2016 among emerging market business corporations, especially those in Brazil, China and Hong Kong, and among financial institutions, particularly in Brazil, China and Russia.

Meanwhile, the interest rate squeeze is tightening. The US Federal Reserve raised its key short-term rate, to a range of 0.5 to 0.75 percent from 0.25 to 0.5 percent in December, and it plans for three rate hikes this year instead of the two originally planned.

Local-currency borrowing rates have risen by 100 to 150 basis points since the US election in the case of Mexico and Turkey and the cost of two-year interest rate swaps, a good indicator of wider market rates, has risen sharply in the case of China and the US especially.

The debt situation in mature markets is meanwhile not good. Again, total debt stood at $165 trillion in the final quarter of 2016 with $50 trillion of that being government debt. Around $95 trillion is in the financial and non-financial corporate sectors and some $20 trillion among households. The big borrowers in debt to GDP terms among mature economies are Britain and Japan with government debt being by far the lion’s share, and then Denmark, Norway and Canada. Corporate creditworthiness continues to deteriorate, and net debt is at a record compared to corporate earnings.

As the IMF points out, fiscal policies are limited in an era with low interest rates. Crisis could be averted with debt restructuring, tax policy reforms that reduce incentives for debt, and regulatory policies that keep debt at sustainable levels.

Governments must also brace and prepare for inevitable, publicly-financed bailouts of banking and, in this case, corporate sectors.

*Anthony Rowley is a former business editor and international finance editor of the Far Eastern Economic Review and is currently field editor (Japan) for Oxford Analytica and Tokyo correspondent of the Singapore Business Times. During a long career in journalism, Rowley has written extensively on issues of economic and financial development in Asia and elsewhere, and his books include Asian Stock Markets – the Inside Story published by Dow Jones Irwin in 1986 as well as The Barons of European Industry, published by Croom Helm in 1973.