Iranians Activism Increasingly Rejecting Not Just The Government But Its Ideology – OpEd

By Hamid Enayat

Recently, there has been an entire category of viral video spreading through Iranian social media which showcases clashes between ordinary citizens and both the political and religious establishment. The videos reinforce widespread perceptions of a still-evolving legacy for two nationwide uprisings that took place in early 2018 and late 2019. Increasingly, they also underscore the fact that such movements are grounded in popular rejection not only of the existing government but also of the entire ideological framework on which it is based.

As one example, a video began spreading in December which showed a female activist lashing out at two clerics in the city of Qom, the Islamic Republic’s center of religious education. The unnamed woman ripped off both clerics’ turbans and stomped on them in a show of disgust at the theocratic fundamentalism that Qom institutions tend to instill in their students. The incident was a notable role-reversal in comparison to numerous other videos that have appeared online in recent years, depicting the Iranian regimes “morality police” violently attacking and often arresting women who are deemed to be in violation of that nation’s strict Islamic dress code.

Backlash against the phenomenon of “forced veiling” has seemingly been a leading indicator of broader upsurges in dissent against the clerical establishment. December 2017 saw the start of a women’s rights movement that came to be known as “Girls of Revolution Street,” which consisted of young activists standing in highly public places, removing their hijabs, and holding them over their heads like a banner or resistance. The first such protest in Tehran coincided almost exactly with an economic protest in the city of Mashhad which marked the beginning of the January 2018 uprising.

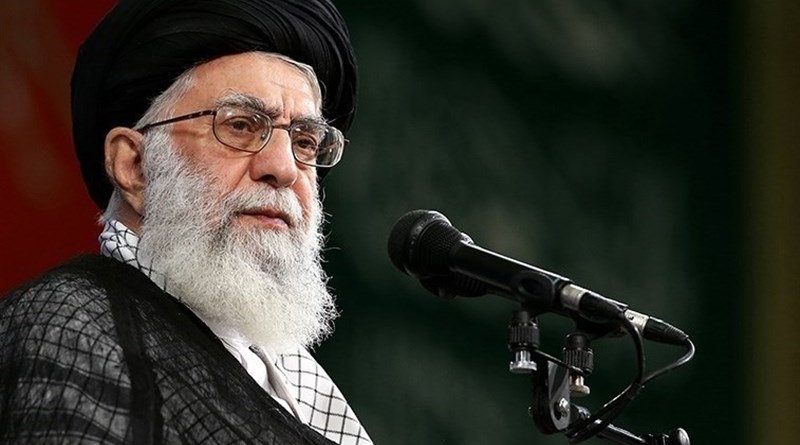

As that uprising spread to well over 100 cities and towns by the middle of that month, it also assumed provocative political messaging, including chants of “death to the dictator” and slogans that rejected both the “hardline” and “reformist” factions of mainstream Iranian politics in favor of leadership from completely outside of the existing establishment. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s reaction to the uprising practically acknowledged that participants were prepared to embrace the country’s leading pro-democracy opposition group, the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran, as the source of that alternative leadership.

The organization’s parent coalition, the National Council of Resistance of Iran, has designated Maryam Rajavi, the wife of PMOI founder Massoud Rajavi, as the prospective leader of a transitional government following the regime’s overthrow. Her appointment to that position would be an important symbol of the change that could be expected in its wake, partly because it would instantly reverse the clerical regime’s commitment to patriarchic leadership, and partly because Mrs. Rajavi’s own Muslim faith is of a moderate form that embraces secular governance.

In fact, Mrs. Rajavi’s ten-point plan for Iran’s future specifically calls for establishing such secularism, along with equal protection under the law for all religious minorities, and of course for women. The 2018 uprising, which Khamenei characterized as the result of months of planning by the PMOI, clarified the extent of public support for the organization’s platform and ideology. That message was reinforced in November 2019 when an even larger uprising broke out, featuring all the same expressions of fundamental opposition to the current regime’s politics and religion.

More recent, smaller-scale demonstrations by Iranian citizens have helped to keep that message alive, especially when those incidents spread on social media or were referenced in reports on traditional Iranian media outlets. Such references are increasingly common, as state media appears to be finding it increasingly difficult to downplay the influence of an opposition movement that authorities long insisted was devoid of serious domestic support.

On January 18, Eghtesad News quoted former presidential candidate Mostafa Hashemitaba as saying that the people of Iran have grown frustrated with inattention to their demands for change. “When people see that everything they say is leading to nowhere,” he said, “they start protesting. Hence there is no bright future on the horizon and the widespread poverty and despair have extremely dangerous side effects.”

A few days later, the online news outlet Jamaran ran an interview with University of Tehran sociologist Taghi Azad Armaki in which he said that “the political system has no will to solve social illnesses.” In other words, there is a fundamental disconnect between the people’s interests and those of the state. Regime authorities are far more interested in maintaining enforcement of the Islamic dress code and otherwise strengthening the country’s religious identity than they are in taking actions that address the people’s essential, material needs.

The state’s religious fixation is also expressed in the financing and logistical support of Shiite militant proxies throughout the region – a situation that has led countless protests in recent years to be defined by chants that implore Tehran to “forget” its foreign entanglements and “think of” its own subjects inside Iranian territory. These appeals have invariably fallen on deaf ears, so it is little wonder that the public’s distaste for the regime’s ideology has found expression in attacks on people wearing the garb of fundamentalist clerics in the streets of Qom.

On January 4, the state-run news outlet Dideban noted that some of the ruling clerics have taken to eschewing such attire when appearing in public, for fear that it would draw the ire of passersby. “Many scholars who want to go to the market or to their businesses, try not to go in clerical garb because people are insulting or cursing them,” the article said, adding, “People blame the clergy for all the problems.”

They have every reason to do so. Ruhollah Khomeini’s fundamentalism co-opted a popular revolution in 1979 and forced the Iranian people to defer their dreams of freedom and democracy for 43 years and counting. The problems inherent in that initial act of theft have only been compounded over the years as the same fundamentalism has fueled more and more disastrous policies at the expense of ordinary Iranians, who overwhelmingly adhere to far more moderate Islamic beliefs, as well as pro-Western political ideologies.

Over time, this divide has come to be reflected, more and more, in the wholesale rejection of the sort of hardline religious instruction being peddled at Qom. The latest official statistics indicate that only between four and five thousand seminary students are enrolled across Iran each year, as compared to over one million university students. What’s more, many of those who complete their religious education nonetheless pursue careers in entirely different fields and “are only clergymen on paper,” in the words of Mohammad Alamzadeh Nouri, a faculty member at the Institute of Islamic Sciences and Culture.

Presumably, many of those after-the-fact dropouts reflect a sincere interest in religious education, coupled with an equally sincere distaste for the particular purpose that such education is expected to serve within Iran’s current system. The state-run newspaper Hamdeli published an article on January 15 that described decline seminary enrollment as an expression of “indifference” to the idea of “supporting the way the country is being run.” But videos circulate of clashes with a shrinking population of establishment clerics, it appears that more and more Iranians are trending away from indifference and toward active opposition to the status quo.