Ghani’s Afghanistan: Policy Options For India – Analysis

Indian analysts are unduly nervous about developments in Afghanistan. What is particularly of concern is this oft-repeated lament that despite investing US$ 2 billion in Afghanistan, India has been marginalised, almost holding the Afghan people responsible for this ‘loss’. One, India is, and remains, the most popular country in Afghanistan – as a role model of a successful developing country, successful economically and as a democracy despite its size, diversity, and low starting point. Two, relations between two nations with such a long shared history and culture, and shared long-term interests cannot be reduced to individual transactions; while both must benefit, calculations cannot be done daily, weekly or even annually. Three, for Afghans, India is the land of hospitals and educational institutions – the money changers at Kabul airport and in the bazaar display Indian rupees, not the US dollar, the Pakistani rupee or the Iranian toran. There are more flights to India than to any other destination save Dubai, which is basically its opening to the world. But maximum bilateral travel is with Delhi.

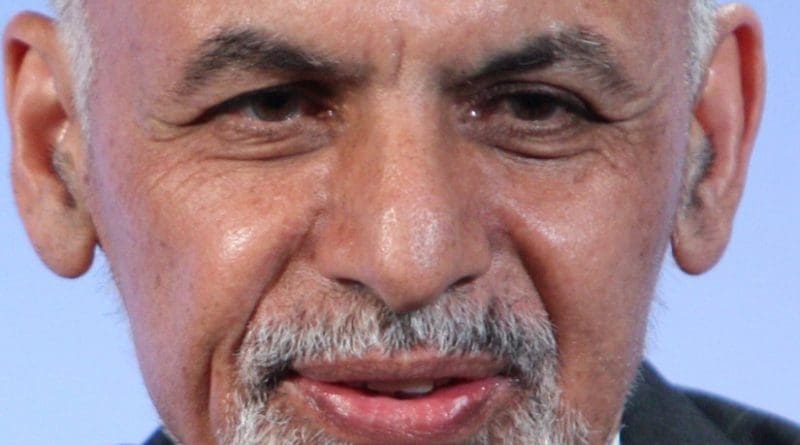

Pakistan, especially GHQ (Rawalpindi, the General Headquarters of the Pakistan Army) is the source of the problem in Afghanistan and there can be no peace and stability without its consent – willing or under duress. Would India like to compare its position with that of GHQ? India is a preferred partner to whom the Afghans voluntarily turn, while with Pakistan it is out of desperation and lack of an alternative. President Ashraf Ghani’s outreach to GHQ is understandable, though it took Pakistan’s political establishment by surprise. But then Ghani was being realistic, for it the army chief not the prime minister who decides and runs Pakistan’s strategic policies. We should also remember that though India sided with the Russian- backed PDPA (People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan), when the Mujahideen came to power, they were quick to seek distance from Pakistan and important elements reached out to India.

Indians should reflect on GHQ’s refusal to let the Taliban and the Afghan government talk to each other even now. Mullah Baradar was just the first to be put through the grinder for trying to respond to former president Hamid Karzai’s outreach. The Taliban are no doubt reliant on the Pakistani army for providing them with sanctuaries, training, arms and ammunition, but as they showed the last time around when they held power in Kabul, they did not agree to recognise the Durand Line as the international border. Hence, they are unlikely to act as puppets.

China is the Pakistani army’s closest strategic ally; the US and Saudis may pick up the tab but the complete congruence of interest in so far as South Asia is concerned is between the Chinese and GHQ. Letting the National Assembly decide whether to lend support to the Saudi-led armed intervention in Yemen was less a sign of the maturing of democracy and more of the army using Saudi’s favourite Pakistani politician, Nawaz Sharif, to deliver the bad news. The Pakistani army wants to keep India unsettled, and China wants to keep India ‘bogged’ down in its immediate neighbourhood. However, as continued unstable Afghanistan can lead to the unravelling of Pakistan, and that would mean that China’s 60 years investment and game plan has failed. Uyghurs of Xinjiang are an irritant, and no more: China is using this ‘threat’, as well as the lure of Afghan minerals, as a smoke screen to sort out Af-Pak. Ghani was right to try and use the Chinese to get the Pakistani army to deliver. If the gambit succeeds, unlikely as it sounds, India would have gained as Pakistan, which is variously described as a rentier/ garrison state can only deliver on peace and stability in its neighbourhood by becoming a normal country. This suits India admirably.

India has acted with considerable maturity in handling this changed environment created by Ghani’s unexpected opening up to Pakistan. India supports, and needs, a stable, democratic Afghanistan where the levers of power are with the Afghans. Afghanistan cannot be allowed to become a safe haven of Jihadis who can carry out acts of violence against India.

India must commit to Afghanistan’s economic growth efforts, something dear to President Ghani. India’s development assistance must continue to support the needs of the Afghans, guided by the priorities of the Afghan government. Evaluation of past efforts should help deliver better in the future; some efforts like the power transmission line over the Hindu Kush and the Zaranj Delaram highway have brought laurels, while others like Salma Dam and the Parliament House project are quite problematic. Innovative delivery mechanisms with greater accountability norms are required to make India’s development assistance more credible.

India should consider, on priority, committing certain sums as budgetary support to the Afghan government as that strengthens the credibility of the Afghan government locally. Afghanistan has been asking for such support.

President Ghani is committed to strengthening Afghanistan’s transport links, particularly the East-West corridor. This has been India’s priority, and our recent demarche to Kabul to include India as part of the Afghanistan-Pakistan transit agreement is a piece of brilliant thinking. It has already delivered its first results – Afghan trucks can carry Indian goods from Wagah to Afghanistan. Earlier they could only bring Afghan goods to Wagah, making it non-viable. If the latest decision does get operationalised, it would go a long way in deepening India-Afghanistan economic relations, and conceivably make Pakistan a stakeholder on this – a big confidence building measure (CBM) in India-Pakistan relations.

Government of India’s recent decision to upgrade the Chahbahar port on Iran’s Sistan and Baluchistan Coast at a cost of around UD$ 85 million is a step in the right direction. This would provide Afghanistan an alternate route (Zaranj-Delaram-Chahbahar) to the global markets, which would make Afghan exports more competitive and reduce costs of imports. And once sanctions on Iran are history, it would help India access Central Asia directly. Implementation of this project should be time-bound.

Though the SAIL-led consortium won the Hajigak bid over three years ago, till now not even the agreement has been signed. Understanding that actual mining, conversion to pellets etc would not be possible in the near future, India needed to send a strong signal of its support to Afghanistan’s economic growth. Failure to move even formally has reflected badly on India.

India should try and involve the Indian private sector and India’s vibrant domestic NGOs to (i) help the Afghan SME sector grow and generate employment, and (ii) help better deliver government of India’s development assistance. Innovative under-writing/ backstopping etc would have to be explored. The private/ NGO sectors’ project management and capacity development skills should be used using mechanisms to suitably compensate them for their efforts.

India must make it clear to President Ashraf Ghani that our relations are long-term and not dependent on third countries. At the same time, we will not let third countries use Indian presence as a pretext for destabilising Afghanistan. India’s behaviour and actions have and would continue to be sensitive to Afghan sensibilities, allowing no apprehensions that India is involved in any proxy war against Pakistan on Afghan soil. Prime Minister Narendra Modi must commit to India’s continued support to the Afghan government and its efforts to bring peace to, and develop, Afghanistan.

(Shakti Sinha is a former civil servant who has worked in Afghanistan for the UN for three years and coordinated donor support for the Afghanistan National Development Strategy. He can be contacted at [email protected])