Cash In The Time Of Corona – Analysis

By VoxEU.org

Many firms are facing an unprecedented turnover shock as the corona pandemic unfolds. According to this column, insights from the global financial crisis suggest that firms with high levels of cash going into a crisis are not only better placed to weather the downturn but can improve their competitive positions in the long run. During the financial crisis, cash-rich firms were able to continue to invest while industry rivals without cash had to divest. This led to a shift in competition dynamics, allowing cash-rich firms to outperform their rivals when the economy recovered.

By Andreas Joseph, Christiane Kneer, Neeltje van Horen and Jumana Saleheen*

Social distancing measures to slow the spread of the coronavirus have a severe impact on business activity. With offices and factories shut and households under lockdown, many companies see their revenues slump while faced with running costs and increased uncertainty. Companies with large amounts of cash on their balance sheet at the onset of the coronavirus crisis are in a more comfortable spot and might emerge as winners in the post-Covid world.

The value of cash in a crisis

Idle cash might be expensive during normal times, but having cash at hand when a crisis hits can be highly beneficial. Cash provides a firm with an internal source of funds when cash flows decline or when credit conditions tighten and it becomes more expensive to borrow. A firm can use these internal funds to cover its expenditures, pay off debt, replace capital equipment or finance new investment projects (Froot et al. 1993). Furthermore, when asset prices decline cash preserves its value which protects the firm’s net worth. This reduces a lender’s exposure to losses and makes it easier for a firm to access credit (Bernanke and Gertler 1989). Finally, a cash-rich firm does not have to increase its cash holdings for precautionary motives in the wake of a negative economic or funding shock (Almeida, Campello and Weisbach, 2014; Berg, 2018).

Firms tend to hold very different amounts of cash though. In some industries firms hold more cash on average because of larger cash flow volatility and higher hedging needs. But cash balances also vary a lot within industries, with some firms in an industry holding large amounts of cash and others holding very little. Furthermore, cash reserves of individual firms, especially those of SMEs, tend to fluctuate substantially over time. This implies that at the time a crisis hits, some firms in an industry have a lot of cash on their balance sheets while others have little.

Pre-crisis cash-holdings are an important predictor of investment and market shares after a crisis

How important is the liquidity of a firm’s balance sheet when faced with a sudden downturn? While it is too early to tell how Covid-19 will affect cash-rich and cash-poor firms, evidence from the global financial crisis can give some insights. First, cash affects the probability of a firm’s survival. Furthermore, as we show in a recent paper, cash holdings also matter a lot for the investment behaviour and performance of surviving firms, both during the crisis and even more so during the recovery period (Joseph et al. 2019).

What drives this long-run effect? Firms with ample cash at hand can more easily continue to operate during a crisis, replace fixed assets that have depreciated, or seize new, profitable investment opportunities. Their cash-starved rivals by contrast find it difficult to replace existing capital or invest to expand their capital stock. As a result, an investment gap between cash-rich and cash-poor firms opens up during a crisis. This brings about a shift in competition dynamics as cash-rich firms can preserve or even expand their productive capacity while cash-poor firms see theirs shrink. When demand returns and credit conditions improve, cash-rich firms have more capacity to meet this demand and can gain market share. Subsequently they can reinvest their earnings and increase their capacity further. Cash-poor firms, on the other hand, have difficulties catching up and see their positions weaken further. As a result, the investment gap between cash-rich and cash-poor firms that opens up during a crisis period is amplified during the recovery period.

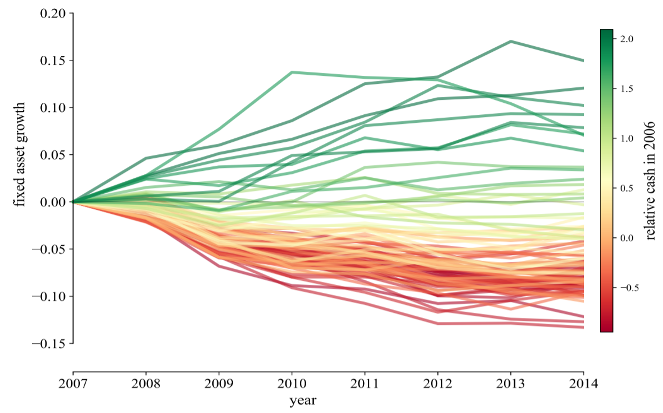

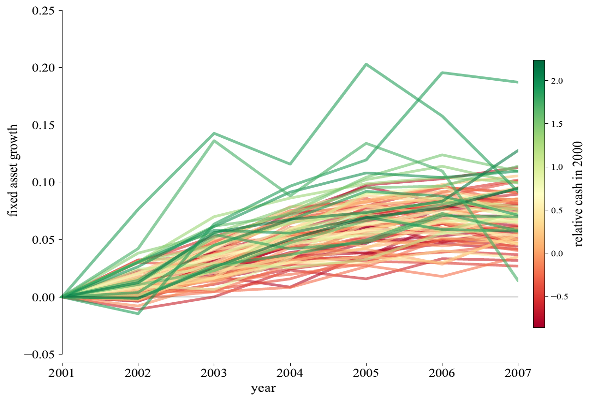

In our paper, we study the investment behaviour of a large number of UK firms and show that this mechanism is indeed at work. In the top panel of Figure 1, we track the investment of UK firms with different levels of cash just prior to the start of the global financial crisis. The fixed asset growth of firms that held small amounts of cash relative to their industry rivals is shown in red. Green marks the fixed asset growth of firms with a lot of cash. Cash-rich firms continued to invest throughout the crisis, while cash-poor firms were shrinking their fixed assets instead. Consistent with cash-rich companies gaining a competitive edge during the crisis, this divergence in investment paths became even more pronounced during the recovery period. Differences in cash-holdings do not seem to determine investment trajectories when the economy is doing well (bottom panel of Figure 1). The investment of initially cash-rich and cash-poor firms between 2001 and 2007 is very similar.

Figure 1 Investment high vs low cash firms: Crisis and pre-crisis period

Panel B: Pre-crisis period: 2001-2007

Estimates from local projections

Using a local projections framework (Jorda 2005), we empirically confirm that the striking patterns shown in Figure 1 are caused by differences in pre-crisis cash holdings and not by other factors. In our analysis we control for a large number of firm characteristics that might explain how much a firm can invest when a crisis hits. We also control for local economic conditions and changes in demand and productivity that affect industry performance.

We estimate that a cash-rich firm (a firm in the 90th percentile of the relative cash distribution) kept its stock of fixed assets between 2007 and 2009 constant – i.e. it was able to maintain its productive capacity. A cash-poor firm (a firm in the 10th percentile) decreased its stock of fixed assets by 5% instead; resulting in an investment gap of 5 percentage points. By 2014 the cash-rich firm had increased its stock of fixed assets by 5%, while the cash-poor firm had decreased its fixed assets by 6%. Thus, the investment gap more than doubled during the recovery period to 11 percentage points. This effect was present both for firms whose cash holdings fluctuated a lot in the period leading up to the crisis and for firms whose cash holdings were very stable. Having high or low levels of cash when a crisis hits, whether due to sheer (good or bad) luck or because of careful cash management, has a strong impact on firms’ long-term investment patterns after a crisis.

So, who benefits most from cash in a crisis? Not surprisingly, it’s the young and the small firms. During a crisis, banks are more likely to cut lending to young and small firms (Iyer et al. 2014). Having access to cash should thus be especially advantageous for these financially constrained firms. Indeed, we find that a young firm (a business that is less than 10 years old) with cash increased its stock of fixed assets by 15 percentage points more over the period 2007-2014 than a young firm without cash and a small firm with cash grew its fixed assets by 19 percentage points more than a small firm without cash.

In line with a change in competition dynamics, we also find that cash-rich firms were able to capture market share from their cash-poor rivals during the global financial crisis and during the recovery phase. And these firms were also able to generate more profits over time.

To conclude

As corporate revenues fall sharply due to the Covid-19 lockdown, companies with large cash reserves find themselves in a more comfortable spot. Insights from the global financial crisis suggest that cash reserves at the time when a crisis hits determine the long-term growth trajectory of firms and provide firms with a competitive advantage over their cash-poor industry rivals. Initial cash balances and the liquidity provided to firms will likely affect the long-term growth prospects of corporates and competition dynamics within industries once the lockdown is over and economic activity resumes. The self-reinforcing dynamics that our research uncovers highlight the importance of policy actions to ease the funding shortages of firms in the current crisis.

*About the authors:

- Andreas Joseph, Research Economist, Bank of England

- Christiane Kneer, PhD candidate at CentER, Tilburg University

- Neeltje van Horen, Senior Research Advisor Bank of England and CEPR Research Fellow

- Jumana Saleheen, Chief Economist, CRU GROUP

References:

Almeida, H, M Campello, and M S Weisbach (2004), “The cash flow sensitivity of cash”, Journal of Finance, 59, 1777-1804.

Berg, T (2018), “Got rejected? Real effects of not getting a loan”, The Review of Financial Studies, 31, 4912-4957.

Bernanke, B and M Gertler (1989), “Agency costs, net worth, and business fluctuations”, American Economic Review, 79, 14-31.

Froot, K A, D S Scharfstein, and J C Stein (1993), “Risk management: Coordinating corporate investment and financing policies”, Journal of Finance, 48, 1629-1658.

Iyer, R, J-L Peydró, S da Rocha-Lopes, and A Schoar (2014), “Interbank liquidity crunch and the firm credit crunch: Evidence from the 2007-2009 crisis”, The Review of Financial Studies, 27, 347-372.

Jordà, Ò (2005), “Estimation and inference of impulse responses by local projections”, American Economic Review, 95, 161-182.

Joseph, A, C Kneer, N Van Horen and J Saleheen (2019), “All you need is cash: Corporate cash holdings and investment after the financial crisis”, CEPR Discussion Paper 14199 and Bank of England SWP No. 843.