‘Iron Silk Road’: Dream Or Reality? – Analysis

By JTW

By Selçuk Çolakoğlu and Emre Tunç Sakaoğlu

A majority of the projects introduced by China within the scope of the ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ vision have yet to reach maturity. Nevertheless, the draft outlines prepared for these projects promise great potential in the eyes of many regional countries including Turkey, which have received relevant proposals with great enthusiasm. A combined budget worth nearly $40 billion will be allocated to these projects through which China is planning to boost its influence over Central Asia, the Caucasus, and the Middle East in particular. Another objective set by Beijing when introducing the projects in question was to promote China as a leader country which is deemed indispensable for regional stability, development, and integration.

As to the prerequisite for the realization of all the Silk Road projects, reinforcing regional transportation infrastructures and improving intra-regional logistic links come to the fore. In that regard, the ‘Iron Silk Road’ project is expected to form the backbone of a greater vision of multi-dimensional cooperation among Turkey, China, and the rest of the region concerned; and raise the level of relations between these countries to the highest level. Within the scope of the ‘Iron Silk Road’ project, the parties involved hope to put into operation a railway line that passes through China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) and Central Asian countries before reaching Turkey and Europe. The new railway line will function as the latest continental land bridge and lay the groundwork for the creation of a vast market that is expected to surpass $1 trillion in cumulative volume by virtue of low tariffs, extensive people-to-people contacts, and improved interdependency.

Ankara’s approach to the subject

The main reason why Ankara receives Silk Road projects favorably, and leans toward the idea of actively taking part in the ‘Iron Silk Road’ project in particular, is the firm belief that commercial relations between Turkey and Central Asian countries will be amplified through the actualization of such prospective projects as soon as possible. Through this project, Ankara is also looking forward to capitalize on its geostrategic advantage that essentially derives from lying at the intersection zone of traditional transport routes connecting Europe and Asia. With this project, it wishes to place itself once again at the center of inter-continental transport routes, this time by way of harboring a major railway corridor between Europe and Asia that will facilitate trade in fossil fuels, minerals, and manufactured goods, alongside agricultural products and other raw materials. Besides, Turkey believes the project will set the scene for closer bilateral relations with China based on mutual trust and substantial economic cooperation as new railway lines envisaged by the project will carry a significant quantity of passengers and freight on both directions between the two countries concerned. Moreover, bilateral economic relations will be protected from the potentially disturbing effects of fluctuations in the value of the dollar thanks to two-way trade in national currencies instead. In sum, the ‘Iron Silk Road’ project is seen as a potential leverage that can allow Ankara to become the ultimate playmaker in the Euroasian arena while increasing its economic and political radius of action.

The first inter-governmental framework agreement on the construction phase of the specific section of the railway that falls within Turkey’s borders was signed in 2010. An overall roadmap for the project’s implementation was determined in 2012, pursuant to a set of consecutive agreements signed in the meantime in order to clarify the technical and bureaucratic details of operation. The agreements in question also pledged contracts to Chinese firms for the construction of a large segment of the project’s relevant section.

Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway

The ‘East-West High-Speed Railway Project’, i.e. the phase of the ‘Iron Silk Road’ project that is to be undertaken by Turkey, will link the eastern Turkish city of Kars with the country’s westernmost city of Edirne. Loans to be provided by Chinese banks, together with Chinese investments, will play a crucial role at this stage. The railway line that falls within Turkey’s borders will reach approximately 2000 km and cost around $30 million in total. However, an agreement is yet to be reached with the Chinese Ministry of Railways for the construction and operation of a high-speed railway that will traverse the whole country along the east-west axis. The completion of the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway (BTK) and the subsequent modernization of all the railway systems between Edirne and Kars to allow for high-speed freight transit is a prerequisite for the realization of the entire project.

According to estimates, the BTK will be able to carry one million passengers and 6.5 million tons of freight per year at the initial stage right after it becomes operational. In a similar vein, the volume of bilateral trade between Turkey and China is expected to double after five years. In the medium term, it is expected to transport 3 million passengers and 17 million tons of goods per year. And in 20 years, the railway will attain the sufficient capacity that would allow it to haul 30 million tons of goods per year.

The construction work at 20 km of railways out of the 76 km-long section of the BTK that lies within Turkish territories is yet to be completed. Moreover, a 4.5 km-long tunnel is still under construction on the border between Turkey and Georgia. According to the State Railways of the Turkish Republic (TCDD), China National Machinery Import-Export Corporation is working in cooperation with Ankara and Tbilisi to finalize the BTK as soon as possible. Indeed, the governments concerned laid the foundations of the BTK in 2008 but the planned finished date has been repeatedly postponed. It was lastly announced that the project will come into operation by 2018 at the earliest.

The ‘Iron Silk Road’ vs. the China-Europe Southern Railway Route

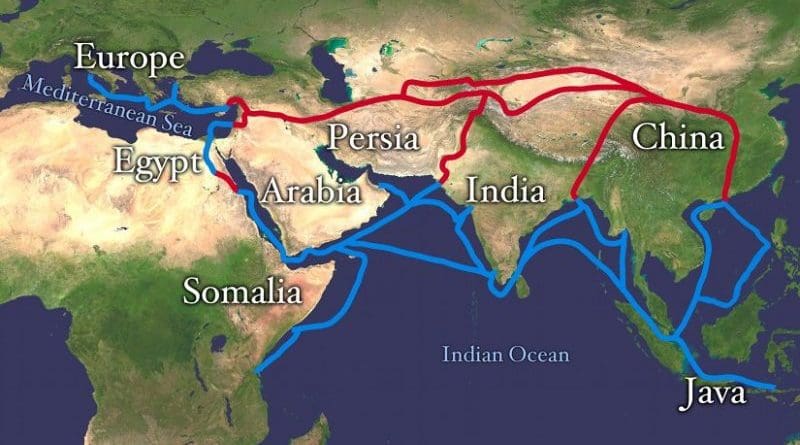

Today, railroad transportation between China and Europe is carried out along three alternative routes. Containers that are first shipped from China’s eastern ports to the Vostochny Port in the Russian Far East are transported to Germany along the Eastern Railway Route via Russia and Belarus. The total length of this line is approximately 11,000 km. The Northern Railway Route, which is approximately 10,000 km long, enables the transportation of goods from Beijing and China’s northern provinces to Germany via the same countries in parallel with the Trans-Siberian railway. Lastly, the Southern Railway Route, which became operational in 2012 and covers a total 14,500 km, conveys goods shipped from China’s inner provinces to the Port of Hamburg via the XUAR, Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, and Poland.

The Southern Railway Route, which was inaugurated in October 2012 and expanded further to reach other cities in inner China in the following years, connects the German cities of Duisburg and Hamburg to the Chinese cities of Wuhan, Chongqing, Chengdu, and Zhengzhou. This route enables low-cost but fast and relatively short-distance transportation between China and Europe. It takes 19 days to transport goods between Hamburg and the most distant Chinese city connected to this route. It is true that transportation along this route takes a week longer than the 12-day period envisaged for the projected ‘Iron Silk Road’. Still, a duration of 19 days is much more favorable when compared with the only other available option – waiting for 45 days before cargo steamers departing from China’s eastern ports arrive in Hamburg. The most salient problem with this line in the eyes of Chinese decision-makers is that it makes no contribution to China’s influence over the rest of Central Asia, the Caucasus, and the Middle East. Therefore the basic motivation behind China’s proposal of the ‘Iron Silk Road’ project appears to be a long-term vision of linking the country’s main trade routes with those passing through the Middle East and Central Asia in an attempt to create a unified network of complementary economies with China at the ‘center of gravity’; rather than an urgent need for a new route that would connect China to Europe. On the other hand, Turkey is inclined to perceive of this project as a complete alternative to the China-Europe Southern Railway Route, which constitutes the southern branch of the already existing Eurasian land bridge.

Alternative routes for the ‘Iron Silk Road’

What the Chinese propose within the scope of the ‘Iron Silk Road’ concept is actually a project that is still in its infancy. There are two alternative routes proposed for the project; and which one will be chosen is a question yet to be answered. The projected railway will either pass through Kazakhstan, the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, and Georgia before it reaches northeastern Turkey; or through Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Iran to reach the southeast of our country. The former alternative in question, if chosen, will cover a distance that is 2000 km shorter than the Northern and Eastern Railway Routes between China and Europe that have been in service since 1970s.

China South Corporation (CSR), a state-owned company in China which is the world’s largest manufacturer of locomotives and rolling stock, estimates that the latter alternative will cover a longer distance than the former – around 6000 km – from XUAR to İstanbul. It will cost around 150 billion dollars, and it won’t be ready to operate until 2020.

Marmaray, the Eurasia Tunnel, and the Third Bosphorus Bridge

Through Marmaray and the Eurasia Tunnel, which are introduced as sister projects, it is claimed that passengers arriving from China will be able to travel from İstanbul to London without any interruption. Marmaray is expected to carry 1 million passengers per day in the future. And if all goes to plan, freight trains will operate non-stop between Asia and Europe by crossing the Third Bosphorus Bridge that is still under construction. However, the construction of an additional 63 km-long high-speed railway will be required for trains that will operate between China’s Western cities and İstanbul’s European side to traverse the rest of Turkish territories on the European continent before reaching border gates. Among the high-speed railways currently operating in Turkey, only the Ankara-İstanbul line (533 km) will be integrated into the ‘Iron Silk Road’ project.

Problems faced

Even though Ankara pins all its hopes on Marmaray, the Turkish phase of the ‘Iron Silk Road’ project is probably going to follow another route instead. The railway’s final destination in Asia can be the Gulf of İskenderun in southern Turkey, the Gulf of İzmit to the country’s northwest, or the Port of İzmir on the country’s western coast. That is essentially because there are technical incompatibilities between the railways that link European cities with each other and Marmaray. Besides, trains that will shuttle between China and Europe via Turkey will be able to follow only a single line if they pass through Marmaray. On the other hand, China-Europe railroads that are in service today consist of two parallel lines, with one exclusive to each opposite direction.

To sum up, the ‘Iron Silk Road’ project is still face to face with numerous financial, bureaucratic, and technical obstacles. Major challenges include differences in rail gauge between neighboring countries, disconnections within national railway infrastructures, and restrictions placed on the movement of goods and people between borders. For instance due to differences in track gauge, trains are required to stop at bogie changing stations before crossing the border between Turkey and Georgia and those between several other countries on the projected Silk Road route, which causes a considerable loss of time. Moreover, the level of logistic cooperation and political dialogue between Central Asian countries is still low, which makes it utterly difficult to undertake large cross-border projects as such. Finally, large swathes of the territory through which the ‘Iron Silk Road’ will be required to pass are covered with steep and isolated mountains and subject to high security risks. It is a troublesome task to construct and protect railroads that would pass through these territories, parts of which harbor notorious criminal and terrorist groups.

Apart from that, it is underlined that the ‘Iron Silk Road’ project will completely exclude Russia and Armenia in any case. Moreover, an alternative route proposed for the project that is envisaged to pass through the Caspian Sea will circumvent Iran as well. Taking into account the political affinity and economic interdependence among Central Asian countries, Russia, and China on the one hand; and that among China, Russia, Iran, and Armenia on the other, the feasibility of the project comes under serious question from a down-to-earth perspective.