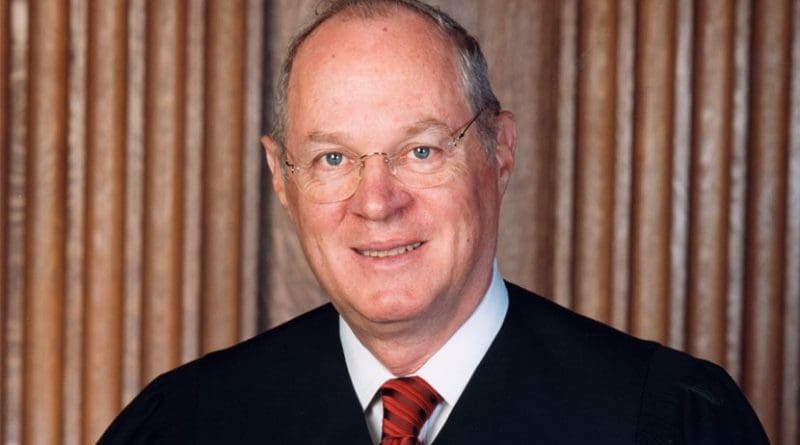

The Middle Man: The Jurisprudence Of Justice Anthony Kennedy – OpEd

“At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.” This near-kitsch description comes from Justice Anthony Kennedy, US Supreme Court justice whose resignation sent Democrats screeching and Republicans chortling with opportunity.

There was a general registered lament from the fearful that Justice Kennedy’s retirement had ended what was, at least in some circles, a terrible period in US jurisprudence punctuated by odd moments of sensible, even delightful refrain. It was, he relayed to President Donald Trump in a letter, “the highest of honors to serve on this Court”, and expressed “profound gratitude for having had the privilege to seek in each case how best to know, interpret, and defend the Constitution and the laws that must always conform to its mandates and promises.”

In being nominated by President Ronald Reagan in November 1987, Kennedy came as a mere third choice in the aftermath of Justice Lewis Powell’s retirement. Robert Bork of the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit failed to impress the Senate, and his nomination sank by a vote of 42 to 58. Douglas Ginsberg came next, but fell foul because of his use of marijuana as an adult. The whirligig of time did the rest.

It is worth iterating that Reagan was confident enough with his third choice to claim he had gotten a “true conservative”, though Kennedy seemed to induce a degree of dissatisfaction over the issue as to whether he was that true. His tendency to seem, at least, like a compromiser did not impress some, though it did win over the centrists.

When it came to decisions, Kennedy could be relied upon to threaten those conventions held dear to progressives. This, it was said, was simply him being the middling man, sporting a libertarian streak. On abortion, he flirted with reasoning that came awfully close to undermining Roe v Wade, a canonical case found along the fault line of Supreme Court battles. While a woman’s right to have an abortion remains intact, Kennedy was not one to entire ignore a pitch at altering it.

Wobbling somewhat, he would write in a joint judgment with Justices O’Connor and David Souter permitting, for the most part, Pennsylvanian abortion laws to stand, that “men and women of good conscience” could disagree with abortion in principle, being “offensive to our most basic principles of morality, but that cannot control our decision.” Attempts to regulate abortions prior to the foetus becoming viable would fall within the constitution’s protection as long as they did not impose an “undue burden” on the right of a woman to end her pregnancy.

In 2016, Kennedy again joined with fellow judges Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayer and Elena Kagan on the topic in Whole Woman’s Health v Hellerstedt, taking issue with parts of a Texas law which imposed onerous impediments on abortion clinics to focus in that state.

On matters of workers’ rights, he was cool, and, in some cases hostile. Mark Kagan, in a penned peace for Jacobin, was under no illusions, remembering “Kennedy’s apparent glee in the destruction of unions.” He cites an exchange in the case of Janus v AFSCME between Kennedy and the legal counsel for the unions. The good justice, it seemed, was missing the entire point on the issue of union influence in politics. The result was crippling for public sector unions, barring them from charging fees for supplying bargaining services for members.

A considerable softening to Kennedy came in various decisions on the subject of gay-rights jurisprudence. These centred on old notions of discrimination, such as the 1996 case of Romer v Evans, where he formed a majority striking down an amendment to the Colorado constitution barring state and local governments from passing laws prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation. “A State cannot so deem a class of persons a stranger to its own laws.”

In Obergefell v Hodges, Kennedy delivered the Court’s ruling in striking down Ohio’s ban on same-sex marriage, arguing that limiting the institution of marriage “to opposite-sex couples may long have seemed natural and just, but its inconsistency with the central meaning of the fundamental right to marry is now manifest.” He had etched himself into the good books of the rainbow community.

There were those ghoulish decisions that should not be forgotten, despite the effusive commentary on Kennedy’s exploits that dubbed him the “first gay justice”. He joined, for instance, the 5-4 majority upholding the death penalty for juveniles, but would then reflect, as he did in 2005, that the practice be outlawed. He also proved vital in the handing over of the 2000 presidential election to George W. Bush, a decision that did its share of monumental damage to the Republic.

Court viewers and judiciary commenters have unduly ignored the conservative rust with the “Kennedy legacy”. A post- Kennedy world is seen in apocalyptic terms, the possible overturning of Roe v Wade, reining in efforts to challenge capital punishment, and dramatic beefing up of religious freedoms.

The fuss is not merely about the actual legacy of Justice Kennedy, which was often a case of knife-edge consequence and exaggerated efforts at being middling, but the political timing of his decision. “This Supreme Court vacancy,” suggested Dylan Matthews, “will give Donald Trump the power to shift jurisprudence on a range of critical issues. It could wind up being the most important part of his legacy.”

Jack Goldsmith in the Chicago Tribune was even less modest in his description of the retirement, which he sees as “the most consequential event in American jurisprudence at least since Bush v Gore in 2000 and probably since Roe v Wade in 1973.” Such observations are best left at home. Judges do not necessarily do what their appointing masters think they will. Not only is the law an ass; its interpreters can do a fine job of either affirming that point or moderating it.