Talented Artist Khaled Qassim Approved For Release From Guantánamo: But When Will He Be Freed? – OpEd

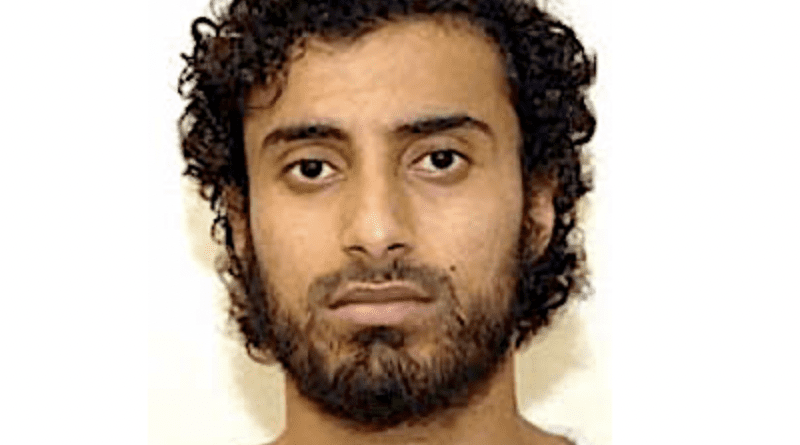

20 years and two months since the Yemeni prisoner Khaled Qassim (aka Khalid Qasim) arrived at Guantánamo, where he has been held ever since without charge or trial, he has finally been approved for release. 25 years old at the time his capture, and frozen in time in the only known photo of him, taken at Guantánamo in the early years of his imprisonment, he is now 45 years old, and has, as a result, spent almost half his life at the prison.

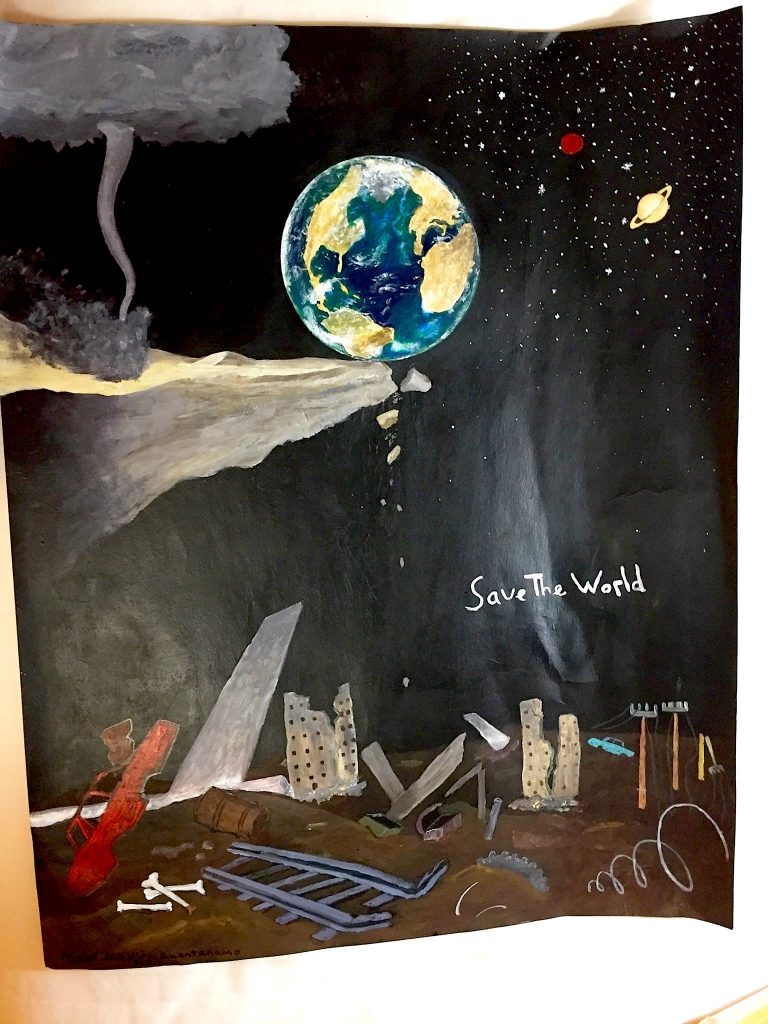

The announcement that Khaled has been approved for release is wonderful news, as those of us who have been studying Guantánamo closely know that he is a talented artist (I posted an article about his art when it was shown in New York two years ago), and, in addition, we learned via his close friend, the released prisoner and author Mansoor Adayfi, that he is also a natural leader, a beautiful singer, a writer, a teacher and a talented football player.

Mansoor told us that Khaled’s natural leadership abilities meant that, in 2010, a Navy Commander said of him, “We like Khalid to represent all the detainees. He talks like a poet when he speaks on behalf of the detainees, and he’s an easy man to deal with,” although he was also, in the prison’s early years, a persistent hunger striker, one of around dozen young, mainly Yemeni prisoners who, as Adayfi explained in his powerful memoir, “Don’t Forget Us Here,” published last year, countered the US’s brutality and injustice with perpetual resistance, as did Adayfi himself.

Khaled is the last of the “red-eyes,” as they were known, to be still held at Guantánamo. Shockingly, Adayfi’s book explained that five of the men died, reportedly by committing suicide, although that assessment has been repeatedly challenged, while the others have all, over the years, been released.

Khaled, however, failed to play the necessary game to secure his release — showing sufficient contrition during the Periodic Review Boards, a parole-type process convened by President Obama to bypass obstruction by Republicans in Congress to the release of prisoners. In 2015, a PRB refused to recommend him for release not because of anything he was alleged to have done before his capture (he was not alleged to have done more than receive military training in Afghanistan), but on the basis of his “significant noncompliance” while imprisoned at Guantánamo.

However, this absurd — and stunningly unjust — situation continued for another seven years. At the end of 2021, another PRB refused to recommend him for release, despite acknowledging his “low level of training and lack of leadership in al Qaida or the Taliban,” because of his “inability to manage his emotions and actions,” his “high level of significant noncompliance in the last year,” and his “lack of plans for the future if released.”

Finally, however, after another review was scheduled for May this year, and Mark Maher, one of his attorneys, wrote a glowing testimony about him, calling him “a good man, with a lot to offer this world,” who is also “extraordinarily thoughtful, kind, and funny,” and “humble too,” Khaled has at last been approved for release.

In their final determination, dated July 19, the board members noted that, although he “has made threatening statements in the past year,” they believe that “the threat he may pose can be mitigated.”

They added that, in making their decision, they “considered [his] low level of training and lack of a leadership role in al Qaida or the Taliban, [his] candor in answering questions from the Board regarding his pre-detention activity and motivations, [his] improved compliance and acceptance of responsibility for prior non-compliance, [his] willingness to work on how he manages his emotions and frustrations in detention and efforts to be a positive influence on camp life, the support available to [him] from his counsel and outside organizations if he were to be transferred and [his] efforts to improve his post-detention plans.”

Regarding security arrangements in connection with his release, the board members recommended “[t]ransfer to a country with a strong rehabilitation and reintegration program and appropriate security assurances as agreed to by the relevant USG departments and agencies.”

But when will Khaled — and 20 other men approved for release — actually be freed?

This good news must, of course, be tempered by the realization that Khaled now joins a queue of other prisoners also awaiting release — 20 in total, out of a prison population that now numbers just 36.

15 of those men have been approved for release by PRBs since President Biden took office, one was approved for release under Donald Trump, while the three others have, shamefully, been waiting since 2010 to be freed, when Obama’s first review process, the Guantánamo Review Task Force, approved them for release. The last of the men awaiting release is Majid Khan, a Pakistani who is awaiting freedom because the prison sentence he served, in exchange for becoming a cooperating witness, has now been served.

While we must all acknowledge that it is difficult to release the Yemenis, who make up nine of the 20 men, because Congress has banned repatriations from Guantánamo to Yemen, and third countries must be found that will offer them new homes, there does not appear to be any obstacle preventing other men from being sent home — to Pakistan, Algeria, Saudi Arabia and Kenya, for example.

As a result, it is hard not to conclude that President Biden isn’t prioritizing their release — as though there is nothing untoward about continuing to hold men approved for release indefinitely. While it is commendable that there are now just four men explicitly held indefinitely without charge or trial as “forever prisoners” (down from 22 when he took office), it must also be remembered that he has released just four men since he became president — the last two of the 38 men approved for release by PRBs under Obama, a mentally ill Saudi, and an Afghan with the distinction of being the only man in over a decade to have a court order his release.

Only in Guantánamo could such contempt for the law, for justice and fairness continue to thrive, and President Biden should realize that, just because no mechanism exists to compel the granting of freedom to men approved for release from Guantánamo, that doesn’t mean that continuing to hold them is anything other than a profound abdication of moral responsibility.

These men have suffered enough, and the State Department should — and must — step up its efforts to get them out of Guantánamo so that they can begin to rebuild their lives.