Changing Trends In Warfare: Private Military Companies And Iraq War

On March 19, 2003, when Iraq was invaded by US forces, backed by the ‘Coalition of the willing’, little was known that this war would become a prime source of profit for private military companies (PMC’s). While the aspect of private warfare is being overtly discussed in the media, it is important to trace the evolution on PMCs in warfare, their role in the Iraq war and the changing trends in warfare. Carlos Ortiz defines PMCs as “legally established multinational commercial enterprises offering services that involve the potential to exercise force in a systematic way and by military means and/or the transfer or enhancement of that potential to clients.” (1)

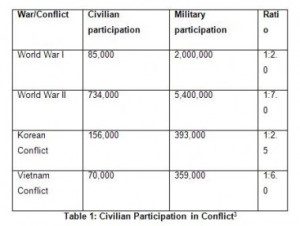

Looking at history books, one can observe that PMCs are not a new entity in the field of security and warfare. They have been a part of the combat environment since history. The practice of deploying mercenaries (2) dates back to the 13th century B.C when they were employed by Greeks, Roman, Egypt, Rameses II etc. and the trend continues to be a part of the contemporary times. Interestingly, PMCs can be viewed as an ‘advancement of the mercenary culture’. Consequently, civilian participation and PMCs are not a new entity in the combat environment. The numbers in Table 1 clearly indicate the tendency of state to rely on PMCs and how that has augmented over a period of time.

Civil participation formerly included civilians who accompanied combatants for logistics and mercenaries. With the modernisation of wars, military started employing private firms that could offer highly sophisticated weaponry systems and personnel to operate them. This was prominent in the Vietnam War which was also called a “war by contract” by Business Week in March 1965. (4) The end of Cold war further boosted the private military industry due to the downsizing of national armies and growing global instability. Even though, a pattern of increase in the use of PMCs is evident in subsequent wars, the Iraq war is a perfect example that reflects a slant towards more dangerous trends.

Civil participation formerly included civilians who accompanied combatants for logistics and mercenaries. With the modernisation of wars, military started employing private firms that could offer highly sophisticated weaponry systems and personnel to operate them. This was prominent in the Vietnam War which was also called a “war by contract” by Business Week in March 1965. (4) The end of Cold war further boosted the private military industry due to the downsizing of national armies and growing global instability. Even though, a pattern of increase in the use of PMCs is evident in subsequent wars, the Iraq war is a perfect example that reflects a slant towards more dangerous trends.

It may be argued that if civilians have been a part of wars previously, then why PMCs are loathed for their participation in present conflicts, particularly Afghanistan and Iraq. What makes this subject important in the history of warfare is not the involvement of PMCs in the war field. Rather, it is the degree of their involvement in military and non-military functions that make them worthy of attention.

The invasion of Iraq required high number of forces and could have increased during the course of the war. In domestic terms, sending in regular troops was not an easy decision because the regular US forces were thinned with multiple global commitments. Additionally, such a decision could have sparked public outcry. The decision of invading Iraq had not received positive response globally and was subject to intense opposition from the international community. Therefore, the probabilities of receiving troops from other countries were minimal. An alternative for the US was to turn to UN or NATO. As US was not willing to offer tough commitments like handing over command of forces to UN or NATO, even this option was not viable.

Under such stressful condition, the easiest solution was to approach the private military industry. Therefore, PMC’s came to the rescue and deployed their forces. Forces deployed by PMCs filled the gaps of insufficient troops and bore no political costs to the US government. Initially, few PMCs participated in the war, but as the war progressed, number of contracts given to them swelled. (5)

In 2007, an internal census of Department of Defense stated that almost 180,000 private contractors were employed in Iraq. In contrast, there were approximately 160,000 U.S troops stationed in Iraq in the same year. Here, it is important to note that private military firms were excluded in the census. The inclusion would have made the figures much higher. (6) Employing PMCs consequently makes it easier for the decision-makers to evade political costs and implement their decisions. At times, these decisions may not be in congruence with public support. It cannot be disputed that US did not enjoy immense support domestically or internationally when it planned Iraq’s invasion. Therefore, PMC’s were deployed without creating any political costs for the war-goers. Iraq is not the only case. This was also practiced visibly in the Balkans and secretly in Columbia and Sudan.

As mentioned by Peter Singer in an interview, ‘…contractors offer the means for choices to be dodged at the onset of deployment, and for scrutiny and public concern to be lessened after deployment. Your home-front does not get as involved when its contractors are being called up and deployed…’ As reflected in the above statement, it is easier for policy-makers to go on a war without attracting much congressional and media scrutiny. This marks the extent of influence PMC’s have in present-day warfare. Affairs that required Congressional approval can now be easily implemented with the tactical use of the private military industry. Another important facet of this practice is observed by Francesco Francioni who notes that, “…a country can also exceed the limits on the number of troops deployed or allowed to serve in a theatre of military operations.” (7) Consequently, these traditions would eventually reduce the credibility that states have enjoyed among its subjects so far.

However, it is important to realise that the PMC’s deliver optimum results only if the scenario is conducive for them to operate. PMC’s are seen favourable in cases where other countries are reluctant to participate or lack enough foreign interest or motivation. Tracing back history, Sierra Leone benefitted from employing Executive Outcome (EO). As noted by C Spearin, Sierra Leone’s military appreciated EO’s effort and did not consider them as mercenaries rather people that bought some sanity. (8)

The advent of PMCs has made warfare an easier business. One of the prerequisites of waging any war is to contact PMC’s and negotiate a deal. Such ease makes a government reliant on contractors and also makes unjustified or illegal wars by far, doable. Hence, PMCs offer the possibility of circumventing the parliamentary procedures and authorization for specific missions. When viewing this through the political lens, it is predicted that the level of reliance would only increase with time. The exercise of not employing soldiers for missions and using PMC’s would shrink the effectiveness of national mechanism of control over defence forces.

Moving ahead, let us amplify the issue of increasing privatisation in military activities. The contemporary age belongs to globalisation and liberal trading practices. Interestingly, ‘privatisation’ and ‘outsourcing’ are defining characteristics of a globalised world. The currents of globalisation have also affected the behaviour of the state. As stated by Anna Leander, “State authority has moved upwards to international or regional institutions, sideways to firms and markets, but also downwards to (sub-national) authorities or regions.” (9)

Industries which were previously limited to the state authorities are now shifting towards private domain such as communication and transportation. Similarly, privatisation has enveloped the defence industry. Kathryn Peters states three major reasons for the rising importance of PMC’s: reduction in military personnel, increasing privatisation and outsourcing of military functions and growing reliance on PMC’s to maintain and operate highly technological weaponry. These reasons are embedded in the practices during the invasion of Iraq and visibly influence the trends of warfare. (10) Consequently the realm of warfare is shifting from the state, the protector of public interest, towards private actors which are solely driven by profits. This would overthrow the state centric conduct of war and diminish the level of sovereignty held by the state.

Today, core military functions are gradually being outsourced to private firms. The invasion of Iraq increased the influence of private firms in warfare. In the past wars, field training, logistics and support functions were considered worthy of outsourcing. Surprisingly, during the Iraq invasion, there were multiple other functions that crept into private hands.

Critical roles being outsourced include military intelligence and security of key military personnel. The significance of PMC’s can be clearly understood by the fact that the head of Coalition Provisional Authority, Paul Bremer (top US official in Iraq) was protected safeguarded by delegation of the Blackwater/Xe Services LLC firm. (11) The growing outsourcing is the result of the extreme reliance of forces on highly intricate and technologically-advanced weapon systems. Undoubtedly, the evolution of warfare demands weapons that offer high precision and the capability to inflicting maximum damage in no time. Dependence on PMCs for operating and maintaining complicated weapon systems is evident from the following illustrations.

The launch-pad for the invasion in Iraq was at Camp Doha in Kuwait. The launch-pad was constructed, operated and also safeguarded by a private contractor. Apart from the conventional roles, PMCs were also responsible for fuelling and operating highly sophisticated combat and air defence system. Additionally, they also armed with extremely sophisticated aircrafts, such as F-117 stealth fighters, U-2 reconnaissance aircraft, and Apache attack helicopters.

Let us address the trend of using private contractors by the following illustration. A few years back, Department of Defense (DoD) Directive 1130.2, Management and Control of Engineering and Technical Services, was formulated which made it essential for regular defence personnel to attain self-sufficiency (in almost 12 months) in the maintenance and operation of new weaponry, thus restricting the dependence on private firms. Presently, that directive has been wavered off, forcing the military personnel to rely on PMC’s for its operation. Evidently, the trend has changed and this marks a period of extreme reliance on PMC’s without a second thought. (12) This change is seemingly due to the high costs involved in training and maintaining military staff for new armaments. Downsizing is what makes it essential for contractors to accompany the weapons and perform military functions, making warfare a profession of the public domains.

It may be argued that outsourcing offers some advantages to the military staff as it minimises the range of activities for the combatants and they can concentrate on the core function of confronting the enemy. Seeing the debate in this view may be beneficial, but partly. Too much dependency on civilians for performing core military functions can prove disastrous in terms of crisis and increased hostility. As we see private contractors operate in an open and unregulated market, anyone with the potential money to hire them can approach them. Therefore, states are not the only source of contracts for the private firms. They are also recruited by international organisations such as the United Nations, humanitarian organisations, media and NGOs mainly for securing the areas inflicted with conflicts and violence. This perhaps makes it clear that someday any client whether a rogue state, terrorism organisation or failed state can hire PMCs for waging wars.

Now, let us concentrate on the status of PMCs under International standards. As mentioned before, warfare was not always divorced from civil participation. In former wars, especially in small states, with the declaration of war, almost all citizens took up arms and participated in conflicts. (13) Those were times when a clear distinction between combatants and non-combatants was neither necessary nor proposed. With the inauguration of nationalism and state sovereignty, the practice of maintaining national standing armies was followed. This gave rise to the concept of the state acting as a provider of security. Therefore, it was essential for the state to distinguish between the two participants.

Undoubtedly civilians were employed in conflicts for logistical services in the olden wars. This association was universally accepted with the notion that civilians could provide support services to combatants so long as they did not come in direct confrontation with the opponent. Clearly, the contribution of civilians was legal and remains so even today. Contrastingly, the status of PMCs is still not clear under international law.

According to the Article 43 under section, Combatants and Prisoners of War of Geneva Conventions 1949,

The armed forces of a Party to a conflict consist of all organized armed forces, groups and units which are under a command responsible to that Party for the conduct or its subordinates, even if that Party is represented by a government or an authority not recognized by an adverse Party. Such armed forces shall be subject to an internal disciplinary system which, inter alia, shall enforce compliance with the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict. (14)

In regard to this, Colonel Steven makes an interesting observation. He states that the participants who do not qualify for the above stipulated requirements cannot be considered as combatants. He presents particular reasons for not considering PMC’s as combatants. This implies that PMC workforce is not subject to the commander’s internal disciplinary system. In addition, neither are they essentially trained to perform operations in accordance with the law of armed conflict nor is their contractor subordinate to the field commander. (15)

Therefore, contractors are performing combat functions in Iraq without losing their civilians status. Thus, this makes them combatants and non-combatants at the same time, which cannot be an accepted status under international norms. Consequently, under this pretext, PMC’s can be considered illegal combatants on the war front. As a result, states that employ these illegal combatants are violating the laws of war. Even though states have violated laws of war in previous wars, Iraq war is testament to lavish employment of private contractors’ or rather illegal combatants. Thus, it would not be an exaggeration to believe that the Iraq war would not have been possible without private military.

Progressing ahead, let us concentrate on another side of the same coin of accountability held by the private military industry. The dangerous blend of private corporate interests and war bought many issues to the limelight in Iraq. Out of the many dark aspects, lack of accountability and unregulated business were the most prominent.

Remembering the numerous turning points in the Iraq war, some incidences automatically come to the forefront. The battle of Fallujjah, the shameful incidence of Abu Ghraib, random shootout Baghdad that killed 20 civilians are just a few prominent ones. Shockingly, one factor common in all these incidences is the involvement of the PMC’s such as Blackwater (name changed to Xe Services LLC), Halliburton etc.

Commentators like P.W Singer (16) , Colonel Steven (17) and Francesco Francioni (18) draw attention towards the problem of accountability held by PMC’s and the need to regulate the industry on this account. An important factor when considering PMCs is their motive of earning profit. Therefore, their objective would not always match the objective of their clients. The Iraq war has reflected many cases of over-pricing, insufficient services, delays etc, which put a question mark on PMCs as a fair player. Halliburton was accused of overcharging the Iraqi government almost $25,000 per month for each of 1,800 fuel trucks which had to deliver gasoline to Iraq. Another case involved KBR which was challenged by the Pentagon auditors for the justification of more than $200 million. (19,20) While some of the cases are still under investigation, the latest decisions prove their validity.

Furthermore, the state cannot rely on the private firms for tasks that demand high degree of loyalty and commitment. Private firms do not fall under military controls. Hence, the client should have alternatives in case the firm terminates the contract should the hostilities increase. According to contractual terms, a firm has the discretion of accepting or rejecting a particular contract, pulling out of the crisis if the dangers become too high.(21) Thus, in such case the military would be at the mercy of such private actors. The history of warfare has hardly seen examples of such level of reliance on private firms for military action.

During the run-up to Iraq war, almost 183 PMCs which were to contribute to the deployment did not have deployment terms in their contracts, thus leading to delays in getting forces to the warfront.(22) Additional to this, because of the rise of hostilities in April 2004 and mounting cases of contractor kidnappings of July 2004, some contractors terminated their contracts. This resulted in severe shortage of troops and supplies at a time very crucial for the US government. (23)

An added problem in this case is that many PMCs recruit employees with no previous experience in combat or employ people from 3rd party nationals in order to reduce costs. Such recruits have either minimal or no sense of party loyalty or patriotism. Another problem that was seen dominant in the Iraq war was the case of human right violation. Defence forces have been accountable for their acts. They fall under the purview of national courts or International courts in case of crimes or misconduct. Ironically, this does not apply to the forces employed by the PMCs.

Some analysts like Jeffrey Herbst argue that private firms differ from historical mercenaries. He adds that, in order to stay in business PMC’s would wish to hold a dignified reputation in the market. (24) This remains true in cases like MPRI or DynCorp but would not apply to firms such as Backwater/Xe. Private Contractors cannot assure sensible conduct of their employees, primarily because they recruit employees from different backgrounds and do not train them like defence personnel. Also, private employees are bound by contracts and not by an oath like the national armies.

The level to which human rights obligations apply to the PMC’s employee remains ambiguous. This is particularly because the private military industry remains unregulated and operates in an open market. With almost no control of the state over these firms, they violate basic norms and are not even held accountable. Firstly, it is disputed if such obligations apply to private entities and secondly, because the operations and acts of PMCs are abroad, the state cannot bring them to trial.

Contractors of Zapata confessed that they had witnessed private contractors indiscriminately firing not only at Iraqi civilians but also at U.S marines. (25) U.S. Army records show that there were 15 Titan translators and sub-contractors working at Abu Ghraib prison in late 2003 where a number of human rights abuses occurred. (26) In this incidence, all the military officials involved were court-martialled, whereas none of the private contractor was penalised or punished for their acts. This was primarily because the US army did not consider them under their jurisdiction. Consequently, the state cannot be held responsible for the acts of private contractors as the PMCs operate only through contractual terms and not through the state mechanism. Considering the above cases, it is imperative to monitor the private military industry, which is growing at a fast rate yet remains unregulated. Most importantly, the state needs to regulate these firms so that their inclusion in wars does not lead to disastrous consequences in future. Recently, on April 16, 2010, former president of Blackwater Worldwide (Xe Services), Gary Jackson, and four other company officials were indicted for illegally stockpiling automatic weapons at one of its facilities in the US (27). Earlier in the month, on April 1, 2010, the federal government sued KBR Inc., over improper charges to the Army for private security services. (28) Commenting on these cases, Stanley McChrystal, the commander of American and NATO forces said that the use of private contractors to support military and security operations in conflict zones had gone too far. (29)

The significance of private contractors in the arena of war making cannot be denied. With the level of involvement PMCs had in Iraq, we can see them getting intertwined in the art of warfare. The escalating privatisation of military affairs reflects an evolution of warfare rather than determine a completely recent trend in warfare. Undoubtedly, we see a shift in politics and warfare from state-centric to a more privatised form, but it is too early to call it a new trend.

PMCs have been prevalent in the international conflict environment for almost two decades and have achieved new heights with the recent Iraq war. As discussed before, mercenaries and civilians that figured throughout the history of warfare have now cropped up as private military firms. The use of PMCs in Iraq remains unprecedented and marks a towering level of involvement in present style of warfare. Besides this, it cannot be considered a new trend. In the final reckoning, the use of private military organisations in Iraq does not illustrate a new trend in warfare rather an evolution of olden practices.

Aditi Malhotra is a Research Assistant at the Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi

NOTES:

1. Carlos Ortiz, ‘The Private Military Company: An Entity at the Center of Overlapping Spheres of Commercial Activity and Responsibility’ in Jäger, Thomas and Kümmel, Gerhard (eds). Private Military and Security Companies. Chances, Problems, Pitfalls and Prospects, Vs Verlag, 2007, p. 60,

, 2007.

2. Article 47 of Geneva Conventions, 1949 defines mercenaries as ‘a person who recruited locally or abroad in order to fight in an armed conflict, takes a direct part in the hostilities and is motivated by the desire for private gain’, ‘Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol 1)’, Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights,.

3. Colonel Steven J. Zamparelli, ‘Contractors on the Battlefield: What Have We Signed Up For’, Air force Journal of Logistics, 23: 11-20,

4. P. W Singer, Corporate Warriors Cornell University Press, New York, 2003, p. 247.

5. P. W Singer, Corporate Warriors Cornell University Press, New York, 2003, p. 244-245.

6. T. Christian Miller, ‘Contractors outnumber troops in Iraq’, Los Angeles Times, 4 July, 2007

.

7. Francesco Francioni, ‘Private Military Contractors and International Law: An Introduction’, European Journal of International Law, 19(5):961-964, , 2008.

8. C Spearin, Executive Outcomes in Sierra Leone: A Human Security Assessment cited in ‘The Private Military Companies Perspective’, House of Commons- Foreign Affairs, http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200102/cmselect/cmfaff/922/2061322.htm, 2002.

9. Anna Leander, ‘Global Ungovernance: Mercenaries, States and the Control over Violence’, Columbia International Affairs Online, .

10 . Kathryn McIntire Peters, ‘Civilians at War’, Government Executive, July 1996 cited in Colonel Steven J. Zamparelli, ‘Contractors on the Battlefield: What Have We Signed Up For’, Air force Journal of Logistics, 23: 11-20, .

11. Peter W. Singer, ‘The Private Military Industry and Iraq: What have we learned and where to next?’, Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF)- Policy Paper, < http://www.dcaf.ch/_docs/pp04_private-military.pdf>, 2004.

12. Robert D. Kaiser and Richard M. Fabbro, DoD Use of Civilian Technicians, Washington DC: Logistics Management Institute, July 1990 cited in Colonel Steven J. Zamparelli, ‘Contractors on the Battlefield: What Have We Signed Up For’, Air force Journal of Logistics, 23: 11-20, < http://bit.ly/9s3tsW>

13. L. C. Green, The Contemporary Law of Armed Conflict, New York: Manchester University Press, 1994, 99-100 cited in Colonel Steven J. Zamparelli, ‘Contractors on the Battlefield: What Have We Signed Up For’, Air force Journal of Logistics, 23: 11-20,

14. Section II. Combatants and Prisoners of War, Additional Protocol I, Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, < http://www.tamilnation.org/humanrights/genevaconventions/gprotocol1c.htm>, 1949.

15. Colonel Steven J. Zamparelli, ‘Contractors on the Battlefield: What Have We Signed Up For’, Air force Journal of Logistics, 23: 11-20,

16. P.W Singer, ‘Can’t Win With ‘Em, Can’t Go To War Without ‘Em: Private Military Contractors and Counterinsurgency’, Foreign Policy at Brookings, 4:1-21, < http://www.brookings.edu/papers/2007/0927militarycontractors.aspx>, 2007.

17. Colonel Steven J. Zamparelli, ‘Contractors on the Battlefield: What Have We Signed Up For’, Air force Journal of Logistics, 23: 11-20,

18 .Francesco Francioni, ‘Private Military Contractors and International Law: An Introduction’, European Journal of International Law, 19(5):961-964, , 2008.

19.

20. James Glanz, ‘Halliburton Audited for Overpriced Operations in Iraq’, The New York Times, 07 November 2006, < http://www.truthout.org/article/halliburton-audited-overpriced-operations-iraq>

21. Peter W. Singer, ‘The Private Military Industry and Iraq: What have we learned and where to next?’, Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF)- Policy Paper, < http://www.dcaf.ch/_docs/pp04_private-military.pdf>, 2004.

22. David Isenberg, ‘Corporate Mercenaries: Myths and mystery’, Asia Times, 20 May 2004,

23. Peter W. Singer, ‘The Private Military Industry and Iraq: What have we learned and where to next?’, Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF)- Policy Paper, < http://www.dcaf.ch/_docs/pp04_private-military.pdf>, 2004.

24. Herbst, Jeffrey, The Regulation of Private Security Forces, Prepared for the Conference on the Privatization of Security in Africa, hosted by the South African Institute of International Affairs, 10 December 1998 cited in ‘Private Military Companies: Options for Regulation’, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, House of Commons, , 2002.

25. P. W Singer, Corporate Warriors Cornell University Press, New York, 2003, p. 251.

26. Pratap Chatterjee, ‘Outsourcing Intelligence in Iraq: A CorpWatch Report on L-3/Titan’, Corpwatch,

, 2008.

27. Citizen News Services, ‘Ex-Blackwater officials indicted on gun charges,’ Ottawa Citizen, April 17, 2010,

28. The Associated Press, ‘Contractor Sued for Charges to Army’, The New York Times, April 1, 2010,

29. Citizen News Services, ‘Ex-Blackwater officials indicted on gun charges,’ Ottawa Citizen, April 17, 2010,