Reincarnation Of Living Buddhas: A Zone Of Sino-Tibetan Conflict – Analysis

By IPCS

By Jigme Yeshe Lama

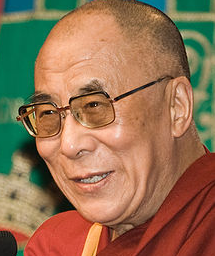

The Dalai Lama had recently announced his resolve to discuss the reincarnation dilemma in the upcoming 11th meeting of the Tibetan religious heads scheduled for the month of September in Dharamsala, India. The reincarnation issue is very crucial in Sino-Tibetan relations as it reflects the struggle over legitimacy and control over Tibetan Buddhism and in essence the future of Tibet and the Tibetans. China and the Tibetans have been at loggerheads for a long time over the scope of religious freedom in Tibet.

The Tibetans particularly emphasize the religious elements while defining their relationship with China. They hark back to the “chos-yon” or priest-patron relationship which was present between the Chinese emperors and Tibetan lamas in the pre-modern period in an attempt to show their linkages with China. With the ascendance of the communists and the Cultural Revolution soon after, Tibetan Buddhism along with the other religions in China suffered a severe setback. A certain unshackling of religious practices and institutions was seen along with state funding in the reconstruction of places of worship, monasteries and temples in Tibet after the reforms of 1978.

This move was partly facilitated by commercial interests and the tourist potential that Buddhist monasteries drew from western travellers. However, numerous restrictions have been imposed and religious activities are strictly monitored in Tibet which reveals the intense competition between the Chinese government and the Tibetans for control over Tibetan Buddhism. This truly came out in the open in 2007 with the implementation of the “Management of Reincarnations of Tibetan Living Buddhas” by the State Administration for Religious Affairs of the Central Government of China. It stated that prior government approval was required for being deemed as a reincarnation or a “living Buddha”. This was implemented under the garb of safeguarding religious freedom of the Tibetans whereby the “solemnity of the law” would be upheld and the purity of all living Buddhas will be validated.

This law calls for a “further legalising of governance” of living Buddha reincarnations and “building a harmonious society”. In effect, this means regularising the state’s role in living Buddha reincarnation. Ostensibly, the rule conforms to customs and traditions and follows historical precedence regarding reincarnations; however, a closer analysis reveals the Chinese state’s desire to control the Living Buddhas, the process of reincarnation and thus the future of Dalai Lama. This rule becomes more important in context of the informal structures of power and influences that are present in Tibet in the form of the Lamas and the Tulkus (living Buddhas). Prior to the control of the Chinese government, Tibet had a unique polity where religion and governance were intertwined and monk officials were in-charge of the administrative apparatus. The Dalai Lama was both the temporal and spiritual ruler of Tibet, who still holds much sway over the Tibetans, irrespective of where they are.

Even when the communists entered Tibet (1951), they cooperated and collaborated with numerous “living Buddhas” such as the Tenth Panchen Rinpoche, who was implanted as a counterweight to the Dalai Lama. In the post reform period (1978), there has been a re-emergence of many charismatic living Buddhas who are involved in philanthropic activities and are able to gain the faith of masses. This is seen as an area of challenge to the legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). On a more important note, the Living Buddhas are regarded as the breathing embodiments and institutions of Tibetan Buddhism, the vessel which transmits the doctrine of the Dharma, thus keeping the tradition alive.

This tradition is closely linked to the Tibetan identity which according to Dawa Norbu (2001) is the single factor which has historically prevented the assimilation of Buddhist Tibet into Confucian China. At present through a communist involvement, a steady process of integration and assimilation has been initiated. In the reincarnation practice, a central idea is also set on the recognition and approval by a higher realized being, in most cases the Dalai Lama, who has given his approval to numerous Living Buddhas inside Tibet so far.

For these reasons precisely, the decision on reincarnation is a major zone of conflict between Buddhist practices and national integrity for the CCP as the Dalai Lama is deemed a ‘splittist’ by the People’s Republic of China. In 1995, the Chinese cancelled the candidate Gedun Chokyi Nyima selected by the Dalai Lama as the 11th Panchen Lama and appointed its own Panchen in the form of the 6 year old boy Gyaltsen Norbu. This was seen as a preparation for the upcoming reincarnation of the next Dalai Lama as the Panchen is a crucial part of the process through which the new Dalai Lama is chosen.

Moreover, with the new act in 2007, the Communist Party has tacitly made its involvement “official” in the process governing reincarnation of the next Dalai Lama which will increase the Sino-Tibetan dispute. China’s not so amicable relationship with religion due to its prior experience of the imperial era, when numerous dynasties were rocked by religious sects and movements questioning the mandate of the ruling dynasties, continues to be one of the reason why the Chinese state remains sceptical about Tibetan Buddhism. This scepticism is likely to increase and become manifest in its handling of the religious entities in Tibet.

Jigme Yeshe Lama

Research Scholar, CEAS, SIS, JNU

email: [email protected]