Social Media Preachers: Unlicensed And Unbounded In Spreading Their Ideas – Analysis

By ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute

By Mohd Faizal Musa*

INTRODUCTION

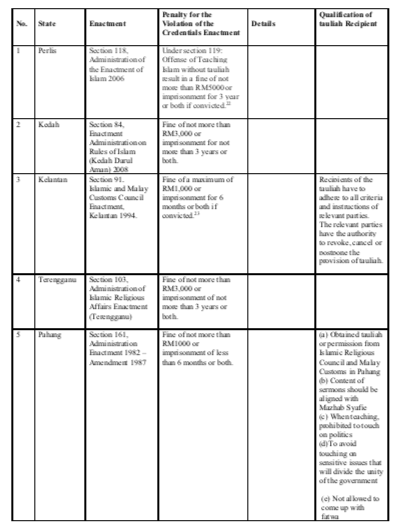

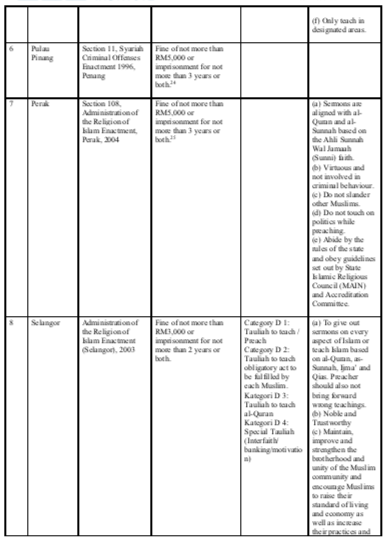

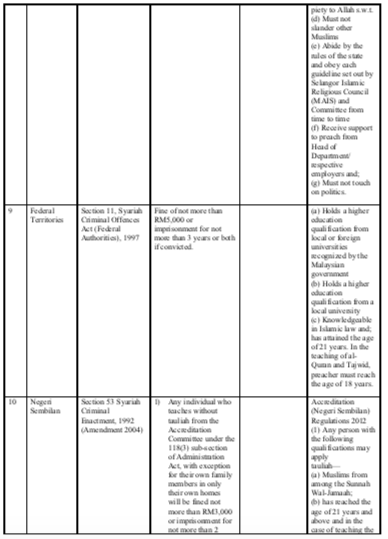

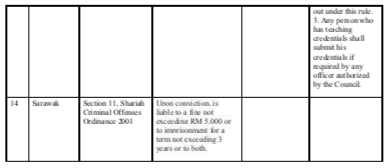

In Malaysia, preachers have to obtain a tauliah or permit to preach should they wish to give sermons in public spaces such as mosques and schools. Failure to do so is a crime under Syariah law and results in the imposition of punitive measures by the local state; in Selangor, preachers can be fined up to RM 3,000 or jailed for up to 2 years or both. Similarly, in the federal territories, preachers can be fined up to RM 5,000 or imprisoned for up to 3 years or both.

Aside from the subjectivity of the charge,1 the provision of a licence is dependent on a set of criteria that differs from state to state. In Pahang, religious authorities ensure that religious teachers abide by only one approved school of thought, Mazhab Syafie, and are not allowed to touch on political matters. Religious teachers are also not allowed to declare their own fatwa (religious edict) and can only teach in designated locations. In Selangor, religious teachers need to “have good morals and trustworthiness”. These teachers must not defame Muslims and “teachings should be aligned with the al-Quran, as-sunnah, ijma’ and qias” (sources of proof within the Sunni school of thought). The set of rules and punishments ensure that the local government can monitor the content of these religious sermons.

Despite the law requiring a licence to preach, there are several celebrity preachers who regularly give sermons without a license, such as the Mufti of Perlis, Mohd Asri Zainal Abidin, Azhar Idrus and PU Azman – all of whom have capitalised on online platforms.2 In January 2020 alone, the percentage of active social media users in religious activities increased from 78% to 81%, and in 2016, then Deputy Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department Datuk Dr Asyraf Dusuki urged preachers to leverage on social media so as to preach more effectively.3

The use of social media is far more effective, harder to regulate and borderless, unlike preaching in mosques where a permit is needed. Religious authorities are hence tightening regulations to curb unregulated content. This was exemplified in 2016 when Datuk Mohd Rawi, Chairman of the Religious, Tourism and Heritage Committee first raised his concerns4 and similarly in 2019, when Dr Mashitah Ibrahim, former Deputy Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department urged religious authorities to increase regulation of these preachers.5

As such, one has to ask if a licence to preach is still relevant now that a religious preacher no longer needs physical space to give sermons and instead can use his personal YouTube account. Social media channels such as Facebook and Instagram have built-in functions that allow preachers to interact with their followers on live stream.

This article will adopt a forensic theology approach to analyse two prominent celebrity preachers, PU Azman and Ebit Lew – both of whom preach without a permit and are able to penetrate the world of social media, amassing millions of followers. This methodology will reveal the preachers’ ideological orientations by analysing their core ideology based on information sourced from YouTube videos, social media posts and books. The article will seek to understand how their ideas are accepted by the online community and explore the increased monitoring of these online preachers’ content.

PU Azman

Background

Azman Syah Elias, better known as PU Azman, is an independent preacher, motivational speaker and actor. He does not have formal education in Islamic studies and became popular in 2014 when he competed in a reality programme, Pencetus Ummah. With his rising popularity, PU Azman managed to secure a license to preach from Negeri Sembilan in 2015 but, it was revoked in 2017 by the Majlis Agama Islam Negeri Sembilan (MAINS) when his teachings were found not to be aligned with Ahli Sunnah Wal-Jamaah (sunni school of thought) and the Shafie Mazhab.6

The revocation of PU Azman’s preaching licence gives rise to questions on his ideological orientation especially since many have speculated that the rescindment was linked to his inclination towards Wahabism. It is thus necessary to determine how far PU Azman’s sermons were actually aligned with the teachings of the Wahabi sect. To unpack this, it is first important to detail the core tenets of the Wahabi sect.

The Wahabi sect is said to refer to pioneering scholars such as Ibn Taimiyyah and to reject popular religious practices such as the celebration of the Prophet’s birthday, saint veneration and practices associated with the mystical teachings of Sufism.7 Wahabis with puritanical inclinations can instigate conflict due to hatred harboured against Shi’ites or Shi’ite sympathisers.8 This thus renders Wahabism inappropriate in Malaysia, as exemplified in the consensus at Mufti meetings in 1985, 1986, 1996 and 1998.9 Wahabism has also been associated with violence due to its history of assaults against Shi’ites and Sunnis.10

Forensic Theology Analysis

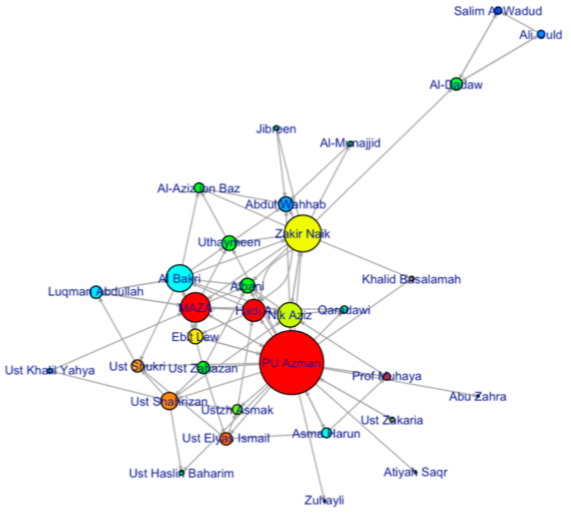

The forensic theology approach is applied here to unpack PU Azman’s ideas and inclinations towards a range of issues in Islam. This methodology allows us to ascertain whether or not PU Azman is a Wahabi sympathiser by looking at his criticism (if any) of Sufis, or the existence of hate speech towards Shi’ite’s practices. A thorough analysis of his ideas is first obtained through his sermons. These are thereafter compared to religious texts of associated doctrines or teachings. The forensic theology approach enables PU Azman’s circle of contacts to be extrapolated by determining who he cites, who he follows and who he admires. The extraction of this circle is obtained through social media, particularly Instagram. His network is illustrated in the diagram below:

As shown in the diagram, PU Azman has relationships with or idolizes Wahabi preachers such as Abdul Aziz bin Baz, Muhammad ibn al-Uthaymeen, Muhamad Nasiruddin al- Albani, Zakir Naik, Zahazan, Mohd Asri Zainal Abidin and most importantly, Muhammad bin Abdul Wahab, the pioneer of the Wahabi school of thought. PU Azman also follows religious experts such as Mohd Asri Zainal Abidin and Zahazan, and referred to Zulkifli Mohamad al Bakri as his friend by congratulating him when he was appointed Minister for Religious Affairs. It is widely perceived in Malaysia especially in social media, that preachers on this list have Wahabi background.

Furthermore, his Facebook status from seven years ago reinforces his orientation towards Wahabism; religious scholars of the Sunni sect such as Al-Zuhaili and Yusuf Qaradhawi are minimally referred to. Instead, these scholars are only mentioned to justify that Wahabism is part of Sunni Islam and should thus not be alienated. His religious orientation is further manifested in some of his sermons where he outrightly demonizes the Shi’ite sect over nikah mu’tah (contract marriage).

Influence of the Wider Audience

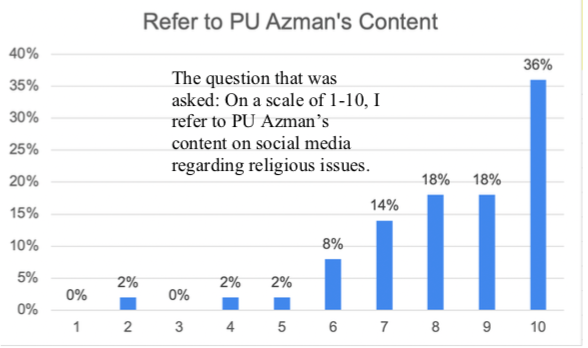

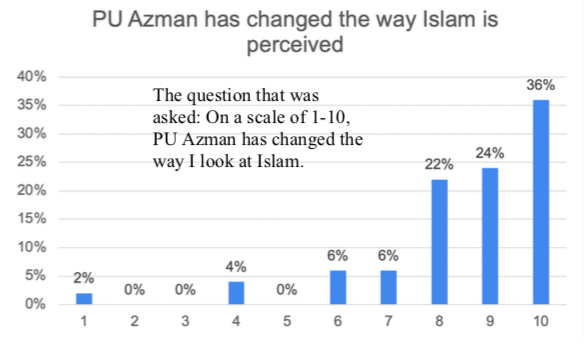

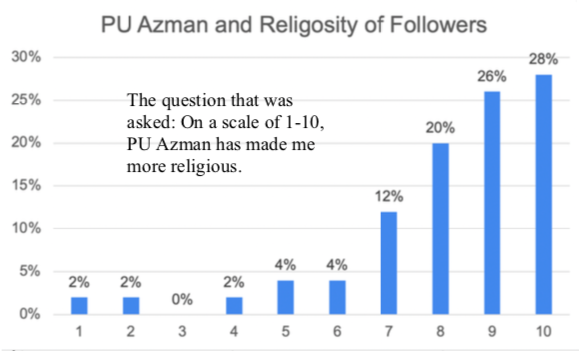

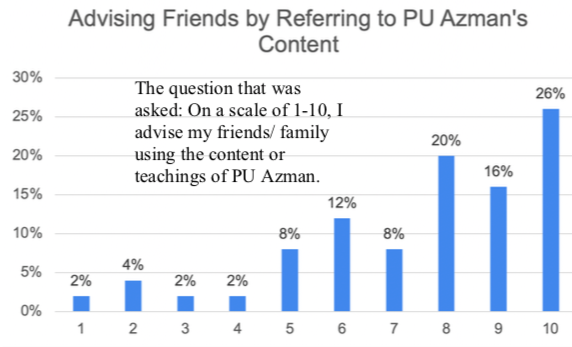

Given PU Azman’s religious orientation and inclination towards the Wahabi sect, it is important to also investigate his followers’ receptiveness of his ideas. PU Azman’s followers on social media are indeed accepting of his ideas; he appears on social media daily and often interacts with his followers on Instagram Live through question-and- answer sessions. PU Azman’s easy-going nature allows him to joke with his followers while simultaneously preaching to his audience. The influence11 of PU Azman as a social media preacher is illustrated in an online survey aimed at measuring the influence he has. Generally, followers of PU Azman idolize him and often refer to his advice for religious issues.

It is clear that PU Azman is not affected by the revocation of his preaching licence. Even without the licence, PU Azman is free to express himself and disseminate his ideas to a wider audience on social media.

As shown in the survey (n=50), PU Azman’s followers resolutely internalise his ideas (when asked if they have ever disagreed with his sermons, an overwhelming majority – 98% respondents answered never), indicating his influence on social media. Given his popularity and the receptiveness of his followers towards his ideas, social media is a primary source for PU Azman to disseminate his religious ideas. The revocation of his licence merely restricts his movement to preach in a designated place, Negeri Sembilan. This, however, has no adverse impact on his online presence; PU Azman is able to amass a segment of the online Muslim population through his interactions on social media, particularly on Instagram, a platform that is widely used by the young in Malaysia.

EBIT LEW

Background

Ebit Lew, also known as a motivational speaker, is a Chinese Muslim preacher who lectures in Thailand, Singapore, Pakistan, India and Indonesia. He was invited to various radio stations and TV channels such as IKIM (Institut Kefahaman Islam Malaysia) to give motivational lectures centred around stress management and Islamic psychology, garnering massive support from youths preparing for examinations.12 Ebit Lew is also known in the community for his charity work where he helps to build and construct homes for the poor, provide food for orphans, and preach to transgender groups.

While it is difficult to ascertain if he was given a permit to preach, Ebit Lew was invited to preach in different states of Malaysia that have strict rules against preachers ascribing to the beliefs of Wahabism. For example, he was invited by the Department of Religious Affairs of Johor to partake in a programme, and to preach in mosques in Kuantan. He was lauded by the anti-Wahabi Facebook group, “Kami Tidak Mahu Fahaman Wahhabi di Malaysia” (“We Don’t Want Wahabi Understanding in Malaysia”). The examples illustrate Ebit Lew’s acceptance by these religious authorities and communities; indicating that they perceive him as a credible Islamic teacher who is not associated with Wahhabism.

Forensic Theology Analysis

To understand his ideas, data on his books and online lectures on YouTube were gathered. It is important to note here that unlike PU Azman, Ebit uses his social media merely to advertise his activities and not really to engage through them. However, he has a significant number of followers on YouTube. In order to understand Ebit Lew, his own writings and lectures are used here as data and not his network mapping. Most of his lectures are transcribed and later published as books.

In Ebit’s many books, he stresses the importance of rituals such as zikr (the ritual prayer or litany frequented by the Sufis) every day and night for a total of 300 times;13 religious rituals to commune with God; and praying dhuha (special prayer during day time) for 8 rakaat to increase wealth.14 In his book, he often refers to experts from tasawuf and sufi sects such as Hassan Basri and Syeikh Yusuf Al-Khandahlawi’s, both of whom advocate warmth, love and care when looking after family members.15

Similarly, Ebit Lew often advocates lifestyle changes and encourages his followers to emulate Prophet Muhammad’s three-way lifestyle: firstly, surah (physical appearance of the Prophet), secondly, sirah (daily practice of the Prophet) and sarirah (Prophet’s thinking/ideas). Doing so, according to him, is granting the Prophet’s wish of a moral, religious and full-of-love society where everyone succeeds in this world and in the afterlife.16 Aside from preaching on spiritual topics such as getting closer to God, his books also reveal his association with the Tabligh movement.

The Jemaah Tabligh movement, an Islamic missionary movement originating from India, pays little attention to social and political situations (apolitical) in Malaysia but is banned in two states of Malaysia, Melaka and Sabah, due to the perception that it steers Muslims towards a path of endless problems, and encourages deviancy.17 Allegations of ‘deviancy’ emerged because the movement urges followers to seek a mystical life to the extent of neglecting their jobs and family.

Despite this, Ebit Lew alluded his activities to jamaah tabligh, referring to the movement as “majlis ta’lim” where family members gather to read the hadith and verses of the Al- Quran. ‘Ta’lim’ is considered one of the doctrines applied by the Tabligh movement. His allegiance to the group is palpable in his many books where he reiterates that he often iktikaf (practice of staying in the mosques for several days, devoting oneself to worship) with members of the group by visiting three mosques in Singapore.18 In this book, Ebit Lew quoted, among others, Syeikhul Hadis Kiyai Uzairon, a Tabligh expert and member of the Syura council in Tamboro, Indonesia.19 He suggested reading books by the Islamic missionary group such as “Muntakhab hadis” written by Maulana Muhammad Yusof Al- Khandahlawi, and “Kitab Fadhilat Amal” by Maulana Zakariya Al-Khandahlawi.20 Referring to these books is another indication of his leaning towards jamaah tabligh.

Ebit Lew’s prominence as a follower of the movement goes unnoticed because he is a successful businessman and entrepreneur. His ideas on Islam, from the lens of the jamaah tabligh, are non-provocative, and aligned with the behaviour and doctrine of the relevant religious authorities in Malaysian states.

His ideas resonate well with members of the Shi’ite community which inadvertently allows him to bridge the longstanding differences between the Shi’ites and Sunnis. In the chapter “Di Mana Islam Tertegak” (“Where Islam Stands”, in the book, Menelusuri Cinta (2015)), Ebit Lew narrated the story of the murder of Saidina Hussein bin Ali, Prophet Muhammad’s grandson in Karbala on the 10 Muharam 61 H. He recounted how Saidina Hussein’s entourage were besieged in Karbala and had limited supply of food and water for 10 days. He further detailed the sufferings and struggles that Prophet’s family members had to go through, and the trauma that Prophet’s great-grandson, Ali Zainal Abidin faced due to the incident in Karbala on the day of Asyura.

Aside from making the sacrifice of Saidina Hussein in Karbala a tipping point that changes the Shi’ite’s whole perception, the narration above is deemed as important especially since the Shi’ite community prioritises the position of the Prophet’s family in all aspects of life. By detailing the story and focusing on the struggles of Prophet’s family members, a key facet that is important and constantly emphasised by the Shi’ites, Ebit Lew managed to signal that his ideas resonate well with the marginalised Shi’ites. His ideas on the murder of Saidina Hussein was put forth in 2015 when discrimination against the Shi’ite community was at its peak.21

Influence and Support in the Community

Ebit Lew has provided assistance to underprivileged groups in Malaysia. Recently, he received widespread media coverage for his community service in Kelantan. Certain segments of the population had started criticising the Kelantan state for neglecting the welfare of the people, unlike Ebit Lew. This reflected the incompetency of certain states and his growing influence.

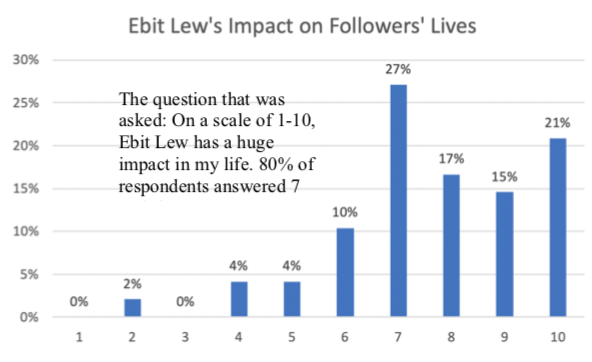

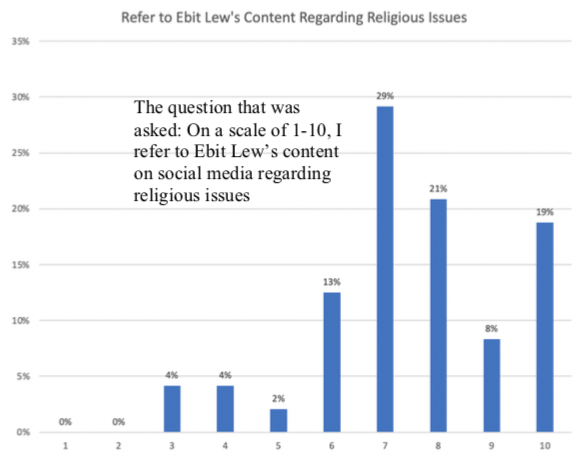

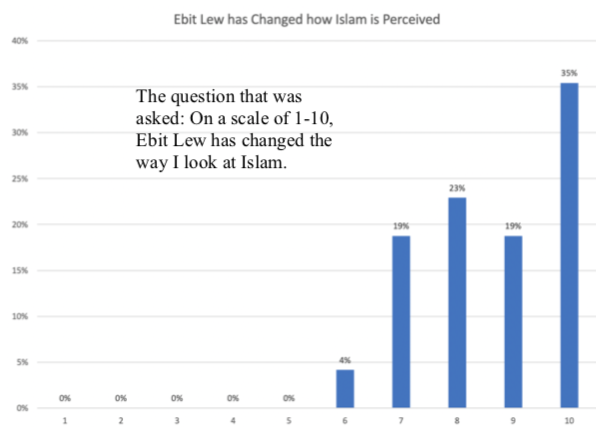

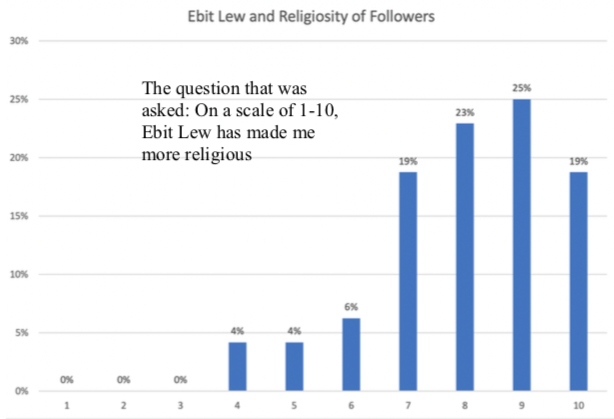

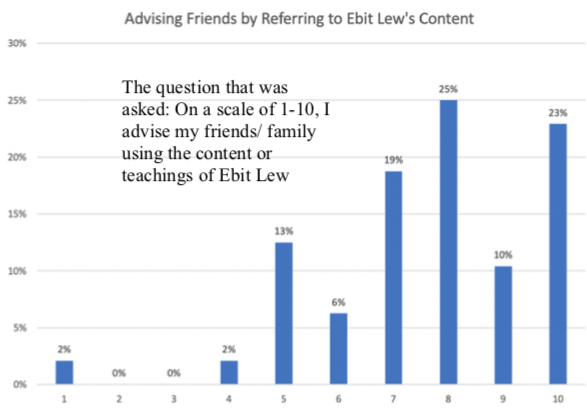

His charity work and motivational lectures centred around religion enable him to garner a number of followers, amounting to over 2 million on social media. A survey (n=48) circulated amongst his followers on Twitter and Instagram showed that he is influential and most of those surveyed viewed Ebit Lew as a positive agent of change in their lives.

It is clear that Ebit Lew’s presence is perceived as non-threatening to the relevant religious authorities since his ideas are aligned with Sunni Islam, yet he also wins the hearts of minority Shi’ites by referring to personalities that are lauded by them. Ebit Lew is thus said to be influential precisely because of the two million followers he amassed on social media; these followers have accepted his ideas as was apparent in a survey that was conducted. Ebit Lew has been able to amass both majority and minority segments of the population, making him more influential than PU Azman who adversely excludes minority groups. Ebit Lew is also non-threatening, in contrast to PU Azman, making the former favourable to the state.

CONCLUSION

Social media preachers such as PU Azman and Ebit Lew (both without licence to preach) are gaining traction in Malaysia, rendering it increasingly difficult for local governments to monitor and regulate their content. With social media, the preaching licence becomes increasingly irrelevant; these preachers’ content is unregulated whereas in public spaces, they have to adhere to a list of criteria. These preachers, as the survey points out, are influential since their ideas are widely accepted and internalised by their social media followers.

In tandem with the influence these preachers have on millions of followers, the various orientations and associations of these preachers are causing anxiety among the religious authorities. Even so, the anxiety differs from preacher to preacher; religious preachers with Wahabi ideological orientation such as PU Azman are seen as a threat unlike preachers who advocate for lifestyle or spiritual changes like Ebit Lew.

Religious authorities, in response, have raised concerns regarding this, urging increased monitoring of content and of the behaviour of religious preachers on social media.

*About the author: Mohd Faizal Musa is Visiting Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. He would like to thank Siti Syazwani Zainal Abidin for assisting with the surveys conducted and the forensic theology analysis.

Source: This article was published by ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (PDF)

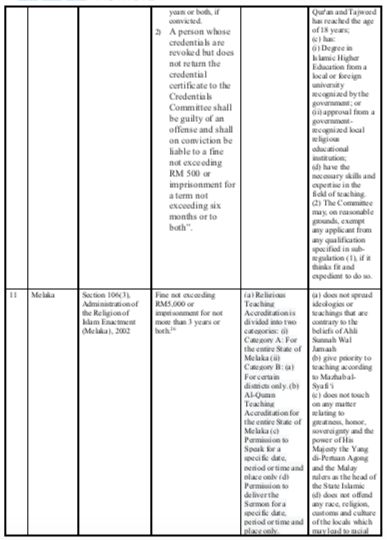

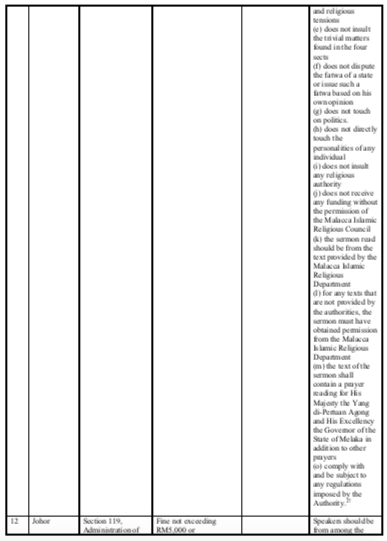

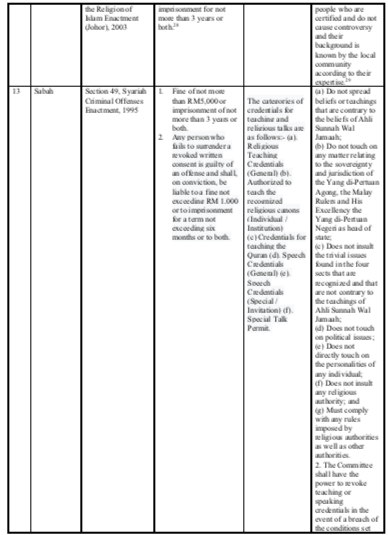

Annex A: Charges in Each State

Annex B: Survey

Notes:

1 Refer to Annex A for a detailed analysis of the charges in each state.

2 Nurul Ain Mohd Hussain. 2009. JAIS sahkan Dr.Asri ditahan kerana mengajar agama tanpa tauliah. Mstar. 2 November. https://www.mstar.com.my/lokal/semasa/2009/11/02/jais-sahkan- drasri-ditahan-kerana-mengajar-agama-tanpa-tauliah

3Malaysia Mail. 2016. Minister urges Muslim preachers to leverage on social media usage https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2016/12/10/minister-urges-muslim-preachers-to- leverage-on-social-media-usage/1269323

4 Aizat Sharif. 2016. Larang pendakwah sesat. Harian Metro. 11 Oktober. https://www.hmetro.com.my/node/173191

5 Bernama. 2019. Tauliah khas kawal lambakan penceramah bebas, kata mufti. 12 Februari. Free Malaysia Today. https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/bahasa/2019/02/12/tauliah-khas- kawal-lambakan-penceramah-bebas-kata-mufti/

6 Projek MM. 2017. Ceramah tidak selari Ahli Sunnah, tauliah PU Azman ditarik. Projek Malay Mail. 10 Jun. https://www.projekmm.com/news/berita/2017/06/10/ceramah-tak-selari-ahli-sunnah- mazhab-shafie-tauliah-pu-azman-ditarik/1396613

7 Christopher M. Blanchard. 2006. The Islamic Traditions of Wahhabism and Salafiyya. CRS Report RS21695. Hlm. 2. Http://www.investigativeproject.org/documents/testimony/47.pdf

8 Daniel Ungureanu. 2011. Wahhabism, Salafism and the Expansion of Islamic Fundamentalist Ideology. Journal of the Seminar of Discursive Logic, Argumentation Theory and Rhetoric. Hlm. 142.

9 Mohd Aizam Mas’od. 2012. Sesatkah Wahabi. Al-Ustaz 19. 30-31.

10 R. Ibrahim dan M. F Samsudin. 2009. Pengikut Wahabi Sukar Dicam. Harian Metro. 6 November. Ad-Din V4. See also M.R Mohd Zin dan Mahfuz Muhammad. 2009. Waspada Tajdid Wahhabi. Utusan Malaysia. 7 November. Rencana, 11.

11 Refer to Annex B for details of the survey

12 Ebit Lew. 2012. Tangisan Umat. Transform Publication. Bangi.

13 Ebit Lew. 2016. Isteriku Bidadari: 11 Kaedah Membimbing Keluarga. Transform Publication. Bangi.

14 Ebit Lew. 2016b. Saya Cuma Posmen. Karangkraf. Shah Alam.

15 Ebit Lew. 2016b. Saya Cuma Posmen. Karangkraf. Shah Alam.

16 Ebit Lew. 2012. Tangisan Umat. Transform Publication. Bangi.

17 Kamaruzzaman Bustamam-Ahmad. 2008. The History of Jamaah Tabligh in Southeast Asia: The Role of Islamic Sufism in Islamic Revival. Al-Jami‘ah 46 (2): 353-400.

18 Ebit Lew & Rahman Lew. 2015. Menelusuri Cinta. Transform Publication. Bangi.

19 Ebit Lew & Rahman Lew. 2015. Menelusuri Cinta. Transform Publication. Bangi.

20 Ebit Lew & Rahman Lew. 2015. Menelusuri Cinta. Transform Publication. Bangi.

21 Mohd Faizal Musa, 2020. ‘Sunni-Shia Reconciliation in Malaysia’. In Norshahril Saat & Azhar Ibrahim (eds.). Alternative Voices in Muslim Southeast Asia: Discourses and Struggles. ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. Pp: 156-182.

22 Guru agama perlu tauliah ajar Islam di Perlis-Raja Muda. Malaysia Kini. 1 December 2017. https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/404028

23 Mengajar Agama di Masjid, surau di Kelantan perlu ada tauliah: MAIK. MStar. 6 Januari 2012. https://www.mstar.com.my/lokal/semasa/2012/01/06/mengajar-agama-di-masjid-surau-di- kelantan-perlu-ada-tauliahmaik

24 Enakmen 3 Tahun 1996. Enakmen Kesalahan Jenayah Syariah (Negeri Pulau Pinang) 1996 http://www2.esyariah.gov.my/esyariah/mal/portalv1/enakmen2011/State_Enact_Ori.nsf/100ae747c72508e748256faa00188094/aca936ad79d38c78482570d70002839d?OpenDocument

25 Azhar Ishak. Semua penceramah kena ada tauliah. 3.12.2019. https://asklegal.my/p/semua-penceramah-kena-ada-tauliah-tapi-kenapa-dan-bagaimana

26 Enakmen 7 Tahun 2002. Enakmen Pentadbiran Agama Islam (Negeri Melaka) 2002 http://www2.esyariah.gov.my/esyariah/mal/portalv1/enakmen2011/State_Enact_Ori.nsf/100ae747 c72508e748256faa00188094/b975844c1cc1d674482572f10019abad?OpenDocument

27 Garis Panduan Pengeluaran Tauliah Mengajar, Kebenaran Berceramah dan Membaca Khutbah Jumaat dalam Negeri Melaka. Jabatan Mufti Negeri Melaka. http://www.jaim.gov.my/Portals/0/Artikel/GARIS%20PANDUAN%20PENGELUARAN%20TA ULIAH%20MENGAJAR.pdf

28 Portal Rasmi E-Syariah. Enakmen 16 tahun 2003 (Enakmen Pentadbiran agama Islam) http://www.esyariah.gov.my/portal/page/portal/Portal%20E-Syariah%20BM/Portal%20E- Syariah%20Carian%20Bahan%20Rujukan/Portal%20E-Syariah%20Undang-Undang/Portal%20E- Syariah%20Undang2%20Johor

29 Edaran Pekeliling Bil 3/2014 Bahagian Undang-Undang Syariah (Tauliah Mengajar dan Memberi Syarahan Agama). 22 Januari 2014 http://pendaftar.uthm.edu.my/v2/doc/pekeliling/Lampiran%20Tauliah%20Mengajar%20dan%20 Memberi%20Syarahan%20Agama.pdf