Turkey: US Sanctions Under The Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) – Analysis

By CRS

By Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas*

Turkey’s July 2019 acquisition of an S-400 surface-to-air defense system from Russia sparked debate about possible U.S. sanctions against Turkey—a longtime NATO ally—under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA, P.L. 115-44). CAATSA requires the President to impose sanctions on those persons he determines have knowingly engaged in a “significant transaction” with Russia’s security sector.

On December 14, 2020, the Administration imposed the following sanctions on Turkey’s defense procurement agency, commonly referred to by the Turkish acronym SSB:

- a prohibition on granting specific U.S. export licenses and authorizations for any goods or technology;

- a prohibition on loans or credits by U.S. financial institutions totaling more than $10 million in any 12-month period;

- a ban on U.S. Export-Import Bank assistance;

- a requirement for the United States to oppose loans benefitting SSB by international financial institutions; and

- full blocking sanctions and visa restrictions on four SSB officials.

In a factsheet, the State Department said that the sanctions “are not intended to undermine the military capabilities or combat readiness of Turkey or any other U.S. ally or partner, but rather to impose costs on Russia in response to its wide range of malign activities.” Additional State Department guidance indicates that the sanctions do not apply to SSB subsidiaries or affiliates.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has condemned the sanctions as a “blatant attack” on Turkish sovereign efforts to establish an independent defense industry. Additionally, political parties representing a large majority of Turkey’s parliament have issued a joint declaration opposing the U.S. decision.

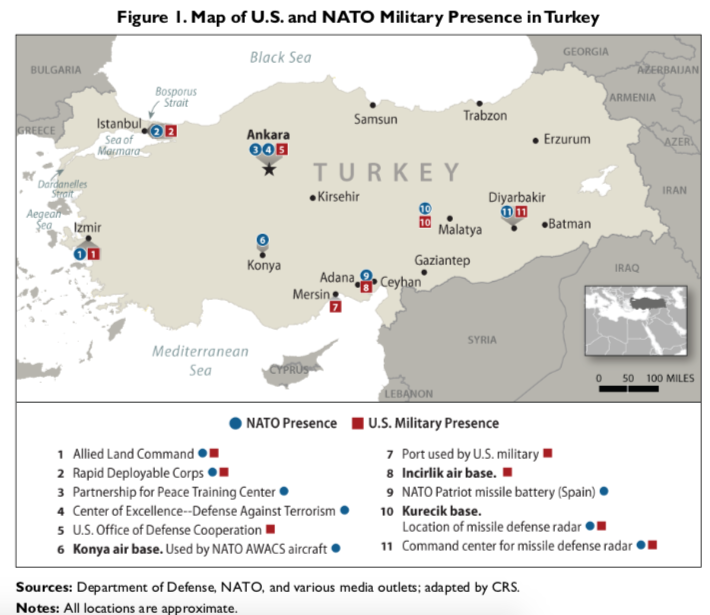

Turkey’s foreign ministry has said that Turkey “will retaliate in a manner and timing it deems appropriate,” while keeping diplomatic options open. A year ago, Erdogan threatened to close Turkish bases to U.S. military personnel and assets in response to potential U.S. sanctions (see Figure 1).

After S-400 deliveries began in July 2019, the Trump Administration announced Turkey’s removal from the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program, given concerns that the S-400 could compromise the F-35’s stealth capabilities. However, despite several difficulties in U.S.-Turkey relations, the Administration delayed imposing CAATSA sanctions while unsuccessfully seeking to have Turkey replace the S-400 with U.S.- origin Patriot surface-to-air defense systems.

Sanctions have come after Turkey test-fired the S-400 in October 2020, and shortly after both houses of Congress passed the FY2021 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA, H.R. 6395). Section 1241 of that bill, if enacted, would direct the President to impose CAATSA sanctions on persons he determines have knowingly engaged in Turkey’s S-400 acquisition.

Possible Effect of Sanctions

At this early stage, forecasts vary regarding sanctions’ likely effect on Turkey’s defense industry, while generally acknowledging some negative effects—at least in the short term—for Turkish exports that rely on U.S. components. One source has said that sanctions would not cancel existing U.S.-Turkey defense contracts, but may directly impact around $2 billion of potential business.

According to a prominent Turkish analyst, Turkey’s military can directly transact some sales with the United States, but the sanctions may handicap U.S.-Turkey—and possibly Europe-Turkey—partnerships to develop advanced weapons platforms. Thus, Turkey may face a choice either to get sanctions removed or turn to alternative suppliers, such as Russia or (perhaps) the United Kingdom for next-generation fighter aircraft.

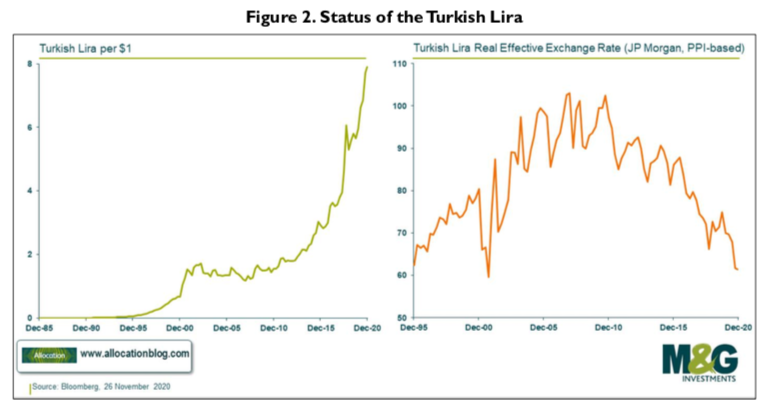

The sanctions could affect Turkey’s economic stability—given the vulnerability of its currency (see Figure 2)—if they disrupt the flow of foreign capital that Turkey needs to cover its financial sector’s large dollar-denominated debts. The early impact on Turkey’s currency has been negligible. The Administration did not opt to impose sanctions that could have more directly targeted Turkey’s financial system.

The S-400 Issue: Assessment and U.S. Options

How the United States and Turkey address the S-400 issue may determine how long CAATSA sanctions remain in force, and define Turkey’s relations with the United States and other countries for years to come. One analyst has proposed that the United States might shelve sanctions if Turkey publicly commits not to activate the S-400. T

urkey has regularly called for a U.S.-Turkey working group to evaluate whether the S-400 might operate in Turkey without compromising U.S./NATO assets, but U.S. officials have consistently rejected any notion of S-400 coexistence with NATO systems. Under CAATSA (as amended by Section 1294 of the FY2019 NDAA, P.L. 115-232), the President may waive or terminate sanctions on certain enumerated grounds related to U.S. national security, or impose more sanctions.

The following factors may affect U.S.-Turkey deliberations on this issue, including under a new Administration and Congress:

- Turkish domestic developments. What effect might sanctions have on Turkey’s economy, defense industry, President Erdogan’s domestic standing, and the breadth of support among Turkey’s leadership class and public for the S-400? Erdogan suffered some setbacks in 2019 municipal elections and has struggled in recent polling, but governs in an authoritarian manner

- and could seek to increase his popularity by attributing Turkey’s domestic challenges to U.S. sanctions.

- Turkey-Russia dynamic. Turkey and Russia each appear to have some form of leverage over the other, based on their support for different sides in regional crises in Syria, Libya, and Armenia/Azerbaijan; their bilateral defense and energy cooperation; and Turkey’s growing partnership with Ukraine. Given this dynamic, what might Turkey demand as part of a face- saving compromise on the S-400? More generally, does this situation present opportunities for U.S./NATO common cause with Turkey to counter Russia, or signal greater Turkish distancing from NATO on how it deals with Russia?

- General U.S. leverage on Turkish foreign policy. How might sanctions, the Halkbank case pending in U.S. federal court, and S-400 deliberations influence or be influenced by Turkey’s regional adventurism, including its confrontational approach with other U.S. partners in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East?

- F-35s and Congress. In the event of a U.S.-Turkey compromise on the S-400, would Congress consider amending an existing provision (Section 1245 of the FY2020 NDAA, P.L. 116-92) that currently precludes the transfer of F-35s to Turkey unless it no longer possesses the S-400?

- Arms sales to other countries. How might U.S. actions regarding the S-400 issue affect U.S. relations with other key partners that have agreed to purchase or may purchase advanced weapons from Russia—including India, Egypt, and Qatar? In a December 14 press briefing, Assistant Secretary of State for International Security and Nonproliferation Christopher Ford said, “We hope that other countries around the world will also take note that the United States will fully implement CAATSA Section 231 sanctions, and that they should avoid further acquisitions of Russian equipment, especially those that could trigger sanctions.”

*About the authors:

- Jim Zanotti, Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs

- Clayton Thomas, Analyst in Middle Eastern Affairs

Source: This article was published by Congressional Research Service (PDF)