The Subsidy Paradox: How EU Cash Props Up Populists – Analysis

Are funds and subsidies from Brussels damaging democracy in Central Europe? Critics of populist regimes say yes.

By Tim Gosling

In the Czech Republic, a billionaire prime minister stands accused of fraudulent misuse of EU funds. In Slovakia, a premier resigns after the murder of a journalist who had probed an EU subsidy scam. And in Hungary, money from Brussels helps an authoritarian leader dismantle democracy.

Call it the “subsidy paradox”: EU cash meant to encourage development ends up misused by populist governments whose very existence undermines the bloc’s cherished values. Worse, it gives them stamina and strength.

“EU funds help sustain national autocracies,” R. Daniel Kelemen, a political scientist at Rutgers University, wrote in a recent paper. “Autocratic rulers can use their control over the distribution of EU funding to help prop up their regimes.”

As member states lock horns over the EU’s next long-term budget, BIRN analysis shows the extent to which EU funds and subsidies bolster illiberal regimes in three countries of Central Europe.

Critics say it is a tale of greed, influence and democratic backsliding, with a cast of characters at the pinnacle of power: Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babis; Robert Fico, head of Slovakia’s ruling SMER-SD party; and Hungarian strongman Viktor Orban.

“Without EU funds, Babis would not be prime minister,” said Lukas Wagenknecht, a senator for the anti-establishment Czech Pirate Party, who formerly worked as Babis’s deputy during the tycoon’s stint as finance minister in 2014-2017.

The same is true of Hungarian Prime Minister Orban and his ruling Fidesz party, said Attila Mesterhazy, a senior official in Hungary’s opposition Socialist Party.

“The money drives the whole system,” Mesterhazy said. “Two-thirds of GDP growth comes from EU funds. Pull that money, and Fidesz would collapse.”

In Slovakia, meanwhile, revelations from an investigation into the murder of journalist Jan Kuciak in 2018 hint at the workings of a “mafia state” for which EU funds are just another prize to plunder.

Waves of cash

A brief history lesson puts the subsidy paradox in context.

After the fall of communism in Europe in 1989, a chaotic process of privatisation sent waves of cash washing through the economic and political systems of Central European nations in the 1990s.

Politicians, oligarchs and criminal gangs raced to grab what they could, to build power bases from which to seize more. Scandals showered down, but the weakness of institutions allowed national interest, democracy and the rule of law to be pushed aside.

Many Central Europeans ended up losing the assets returned to them by the state during the transition from communism to capitalism. Their shares in local industrial giants were bought on the cheap or stolen; the banks and trading houses they owned collapsed as they were asset-stripped.

The democratic system that emerged from the rushed transition was riddled with holes. This has allowed many of the “winners” from that time to continue to dominate the local economic and political systems. And to hunt easy money.

Yet 15 years after the collapse of communism, the EU judged that the rule of law was in rude enough health in the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia for the governments of those countries to oversee a second wave of cash.

EU funds began to pour into the region, aimed at raising the quality of life by developing infrastructure, agriculture, economies, social institutions and democracy. The anticipated lucrative market opportunities for Western companies also helped.

But while the funds have done much good, analysts say Brussels failed to foresee that a rush to steal or misuse this wave of cash might pose almost as big a danger to democracy as the pilfered windfalls of privatisation.

“The corrupt networks were ready and established, dealing with state companies or national funds,” said Karel Skacha, director at Nadacni Fond Proti Korupci (NFPK), a Prague-based foundation that investigates corruption. “EU funds were simply another pie to divvy up.”

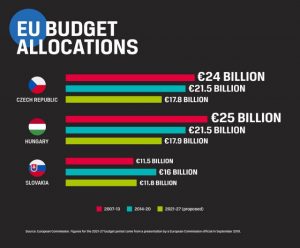

The size of that pie is such that it has tipped the balance of power in these states. In the two full seven-year EU budget periods for which they have qualified, the Czech Republic and Hungary were allocated around 46 billion euros each. Slovakia got 27.5 billion euros.

Analysts say the cash helped nefarious networks penetrate to the top of the Czech, Hungarian and Slovakian political systems.

In the past 12 months, the most powerful men in all three countries have been accused of direct involvement in the corrupt use of EU funds, and of rigging the democratic system to get away with it.

Funding regimes

Exactly how Babis wrangled control of Petrimex, the communist-era Czechoslovak trading company he worked for in the 1980s, and built it into the agrochemicals conglomerate Agrofert — the Czech Republic’s largest private employer — remains unclear.

Some say his time as an agent for the feared communist-era secret police played a part. However he did it, the received wisdom is that he moved into politics in 2011 to give his business empire more clout in a country where mainstream parties had been captured by “godfathers”, as Babis himself put it.

Not long before he founded the populist ANO party, the EU had granted a two-million-euro subsidy intended for small companies to the Capi Hnizdo (Stork’s Nest) leisure resort. Allegations that Babis concealed his ownership of the resort to get the money would dog him for the next decade.

By 2017, the threat of fraud charges over that subsidy forced Babis to lead ANO into a minority coalition supported by the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia. Critics say it also made him subservient to the whims of Czech President Milos Zeman, known for links with Russia and China.

To the east, in Babis’s native Slovakia, Fico was forced to step down as prime minister in 2018 following the murder that year of Kuciak, an investigative journalist who was working on a story on a scam targeting EU agricultural funds in the east of the country, among other corruption stories.

Kuciak had found links between Italian mafia gangs and Fico’s office. The investigation into his murder uncovered evidence that the tentacles of the oligarch accused of ordering the hit reached throughout the political system, the judiciary and the police.

Experts say the most systemic corruption linked to EU funds is found in Hungary, where Orban wields almost unchecked power thanks to a constitutional majority in parliament. Critics say he sits at the centre of an organised network of oligarchs that he has built purposely to tap the public purse.

The Hungarian strongman thumps a nationalist tub and paints the European Union as a bogeyman seeking to dictate to member states, a story that forms part of the bedrock of popular support for his ruling Fidesz party.

Despite his anti-Brussels bluster, EU funds have become Orban’s oxygen. A 2017 study by global accounting giant KPMG and the Budapest-based GKI Economic Research Co shows that money from Brussels more than doubled Hungary’s gross domestic product growth between 2006 and 2015.

Some suggest Brussels should stop sending money to these countries altogether. Others call for stricter regulation and checks. The European Commission plans to make receipt of EU funds conditional on respect for the rule of law.

Still others tout realpolitik, insisting that the only way to start cleaning things up would be for Germany to wield its economic and political muscle in the region to draw a line in the sand.

Degrading democracy

As with the privatisation process in the 1990s, the erosion of democracy that accompanies EU funds has developed hand-in-hand with the abuse, political scientists say.

“When incoming governments set about dismantling democratic institutions, in particular those that are supposed to check executive power, they are simply seeking to gain — and maintain — control over economic resources such as government contracts,” according to a study published last year in the European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research.

“That control, in turn, helps them stay in power, and cements their opportunities to steal more in the future.”

Such systems — presented by political leaders in Central Europe, Russia, Turkey and even the United States as an ideological fight against the “tyranny” of liberalism — tend to degrade democracy at several levels, including the legislative and institutional, experts say.

In Central Europe, most legislation governing public procurement and the distribution of EU subsidies is lifted straight from EU rules, leaving few legal routes to pilfer EU funds.

That means much of the rot is in institutions: the ministries, municipalities and regulators overseeing public procurement, as well as the judiciary, police and prosecutors who might investigate any problems. The media is also key.

Such institutions may appear in order at first sight. A glance at Hungary, for instance, reveals that all the democratic trimmings are in place: an independent prosecutor and constitutional court, an abundance of regulatory offices. The system meets the basic demands of the rule of law more so than in many other EU countries, say opposition parties.

But look closer and you see a Potemkin Village, critics say. Although formally independent of the government, the institutions are stuffed with loyal appointees.

Uncompetitive tenders, underpriced bids and overpriced projects are rife, say non-governmental organisations that try to track and document such abuses, including K-Monitor and its Red Flags portal in Hungary and kamidueurofondy.sk run by Slovakia’s Zastavme korupciu (Stop Corruption).

Meanwhile, when corruption is suspected, authorities often sweep it under the carpet, they say.

‘Mafia state’

Arpad Soltesz was racing around his office in a tumble-down building in the shadow of Bratislava Castle in the Slovak capital. On this sunny October morning, an Italian entrepreneur named Antonio Vadala had just been sentenced to nine years in prison by an Italian court for drug trafficking.

As head of the Jan Kuciak Investigative Centre, Soltesz drives investigations and coordinates international efforts to delve further into the murky story on which the 27-year-old was working when he and fiancée Martina Kusnirova were gunned down in their home one cold February night in 2018.

That investigation, which Kuciak ran alongside colleagues in Italy, revealed that Vadala was connected to the ‘Ndrangheta mafia clan, and from his base in eastern Slovakia was running a scam to claim millions in EU agricultural subsidies. Vadala had links that allegedly reached directly into Fico’s office.

After Kuciak’s murder, fury exploded onto the streets, forcing Fico from the premier’s chair. However, the former prime minister has clung to his decade-long domination of Slovak politics and control of the coalition-leading SMER-SD party from behind the scenes.

The scale and reach of the alleged scams to steal EU funds have stoked that anger. Encrypted messages on the phone of Marian Kocner, the powerful entrepreneur accused of ordering Kuciak’s murder, suggest that Kocner enjoyed an extraordinary amount of influence among senior politicians including Fico as well as judges, police officials and intelligence agents.

Critics say this information backs up long-held suspicions that ever since the rule of Prime Minister Vladimir Meciar, whose authoritarian tendencies and links to organised crime pushed the country into international isolation in the 1990s, Slovakia has been a “mafia state”.

“For many years we lived with the feeling that mafia and politicians, judges, or prosecutors are very often the same things,” Mirek Toda, an editor at the Dennik N daily, wrote on Twitter. “Sadly the murder of journalist #jankuciak proved it was not an illusion.”

The cast remains largely the same through the years, despite numerous scandals.

The “Gorilla files”, a series of secret service recordings leaked in 2012, revealed meetings between Penta Investments — established in the early 1990s and today one of Slovakia’s largest financial groups — with government and opposition figures.

Last year, Penta denied suggestions it was involved in ordering the Kuciak hit. Indeed, while Penta co-founder Jaroslav Hascak had done business with Kocner, there was no evidence that he or the company was involved in the murder.

Corruption watchdogs suspect that much of the public money flowing to larger projects ends up with Slovak oligarchs such as Juraj Siroky, who owns industrial and media assets, and Miroslav Bodor, who runs a security agency reputed to have close ties to the police and 2,500 operatives across the country.

Both men have been around since the days of privatisation and enjoyed links to the Meciar government. Slovak media say that their influence now extends deeply into SMER-SD, as well as the police and security services.

“In many ways, Slovakia is still running on the operating system installed by Meciar,” Soltesz said.

Even so, the era of EU funds has also ushered in new oligarchs — for instance, Jozef Brhel, who moved from the ministry of economy to build a business empire in information technology (IT), energy and defence. Soltesz suspects Brhel is Fico’s bagman.

“There’s a lot of other people involved in stealing this money that you’ve never head of,” Soltesz said.

BIRN was unable to reach Siroky, Brhel or Bodor for comment.

Asked about transparency in the distribution of EU subsidies, SMER-SD’s press department said in a written reply: “The use of EU funds is under the strict control of supervisory boards at the local and European level.”

Experts say the issues surrounding EU funds, and the details of how they are abused, are often mundane. Gabriel Sipos, director of corruption watchdog Transparency International Slovakia, points to a simple lack of institutional capacity.

“Public procurement totals around five billion euros per year; 20 per cent is EU money,” he said.

The scale of EU-funded projects and deadlines to spend the cash both tend to encourage corruption, he added. “But EU funds are just more money for the poorly resourced institutions to deal with.”

Aside from road-building and agriculture, two sectors that are notoriously easy to abuse, experts say IT projects are a major concern in Slovakia.

Watchdog Slovensko Digital — a collective of IT specialists — says the state has spent close to a billion euros in public funds on digitalisation since 2007 and is preparing another half a billion. Much of that money is at risk because of bureaucratic weakness.

The collective’s Red Flags project evaluates state-driven IT projects, but such monitoring is often impossible for non-specialised government auditors, said Pavel Sybila, a senior member of the Progressive Slovakia party, which evolved from a people’s movement after Kuciak’s murder catapulted its vice-chair, Zuzana Caputova, to the Slovak presidency last March.

Further down the ladder, the municipalities lack the staff to write almost any tender. According to Sybila, this has led to the growth of an army of consultants who have effectively become gatekeepers to EU funds. And the most successful have contacts in Bratislava up to ministerial level.

One such consultant who works across the regions — fairly, he stressed — explained how it works.

“They would promise the mayor a successful tender, but on the condition that they select the contractors,” he told BIRN, declining to be identified.

Inside job?

Controlling action by the state prosecutor’s office is key to getting away with systemic corruption, analysts say.

In Slovakia, Dobroslav Trnka — formerly prosecutor general — was arrested in January after police found at Kocner’s house a video of him apparently implicating him in the oligarch’s schemes. He was released on the same day although the investigation reportedly continues.

The prosecutor also reportedly hid recordings of wiretaps from the Gorilla case for Kocner as a means of potential blackmail for those involved in the scandal involving politicians and the oligarchal Penta Investments.

When Trnka left the office after seven years in 2011, Kocner was loath to lose his influence, investigators say. Police suspect the oligarch attempted to bribe lawmakers in a vain attempt to have his man reappointed via parliamentary vote.

In Hungary, by contrast, Prime Minister Orban had no need to finagle the election of a loyal prosecution service. In 2010 he simply installed Fidesz loyalist Peter Polt as chief prosecutor.

Many commentators have described Hungary as a “captured state” following a decade of Fidesz rule in which the party has demolished judicial and media independence. The institutions overseeing public procurement, as well as competition and other regulators, have also been put in yoke, critics say.

The Prime Minister’s Office rejects accusations of conflicts of interest, and insists it has implemented more “stringent rules” than required by Brussels.

“There is no acceptable level of corruption, and the Hungarian government follows a zero-tolerance policy on this issue,” the Prime Minister’s Office said in a statement to BIRN (see box).

A Fidesz spokesperson also said the party “follows the principle of zero tolerance when it comes to corruption”.

“We share the opinion of [German Chancellor] Angela Merkel who said that Hungary uses the EU funds well,” the spokesperson said. “During her visit to [the Hungarian city of] Sopron last year, the German chancellor said, “If we look at the growth data of the Hungarian economy, we see that Hungary uses the money (the cohesion and structural funds) to increase the well-being of the people.”

But the hollowing out of Hungary’s institutions means that legislation that is ostensibly designed to ensure transparent public procurement and competition is not effectively enforced, analysts say.

These institutional gaps, matched with Fidesz’ total confidence in its political power, have encouraged some of the most blatant and persistent abuse in the EU, they add. Critics accuse Orban of sitting at the centre of a network designed to pull billions out of the public purse.

The European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) carried out more investigations into Hungarian EU funding issues in 2018 than in any other EU member state. OLAF recommended that Hungary should pay back 3.84 per cent of the EU finance that Budapest handed out across the country in 2014-2018.

It made similar recommendations for 2.3 per cent of Slovak payments of EU funds. By comparison, the next-highest on the recommendation list was Spain, with only 0.43 per cent of disbursed EU funds in question.

Polt, a former Fidesz lawmaker, is central to the system, critics say. His job is “making sure that Orban’s criminal activities will never see the light of day”, no matter how blatant the cases become, according to Hungarian Spectrum, a blog run by Eva S. Balogh, a former Eastern European history academic at Yale University.

One of the most high-profile cases starred Orban’s son-in-law. Istvan Tiborcz was an owner of lighting company Elios Innovativ, which won dozens of contracts to install EU-funded street lamps across the country.

Aside from an alleged conflict of interest and non-competitive bidding process, OLAF found the contracts to be overpriced. However, the EU’s anti-fraud office has no power to prosecute cases.

For that reason, OLAF recommended that Brussels recoup 40 million euros from the company. It also urged the Hungarian authorities to take action.

A police investigation launched by Polt came up empty handed, while the government withdrew its claim for the EU funds involved. That left Hungarian taxpayers to pick up the tab.

“Hungary has one of the highest absorption rates [of EU funds] of any country, at over 100 per cent,” said Orsi Barsi, head of office and an EU funds specialist at K-Monitor. “It always plans more projects than are covered by available funds so that it can withdraw any that are problematic.”

Neither Brussels nor Budapest offer information on the amount of funds that are actually reclaimed from member states, nor the reasons, she noted.

Members of Orban’s family are starting to populate the list of Hungary’s wealthiest people.

Tiborcz’s real estate company, BDPST Zrt, is the country’s 32nd most valuable enterprise, according to Forbes. Dolomit Kobanyaszati Ktf, a quarrying company owned by Orban’s father, Gyozo, sits at number 88, having won a succession of contracts on state-run infrastructure projects

To run this centralised system, Orban needs more lieutenants than can be found in the family. On larger projects, these come first and foremost in the shape of oligarchs, analysts say.

Some powerful business figures such as Sandor Csyani, who heads banking giant OTP, have survived the Fidesz takeover. Others evolved with the party, only to be discarded.

Lajos Simicska, a former financial director of Fidesz, won many state contracts via construction company Kozgep Plc after Orban took power in 2010, but after the two men fell out in 2014, his success rate plummeted.

Analysis by academics at the University of Sussex and Central European University in Budapest shows the value of contracts held by Kozgep falling to less than 40 billion forints (119 million euros) from more than 120 billion forints (356 million euros) within a year.

Orban’s friend, Laszlo Szijj, took over Kozgep in 2018 and analysts say his star is rising. But Simicska’s primary replacement as Hungary’s most powerful oligarch is Lorinc Meszaros, mayor of Orban’s home village of Felcsut.

Meszaros, a former gas fitter, owns hundreds of companies and last year topped Forbes’s Hungarian rich list.

Hungarian Hungarian investigative journalism outlet Atlatszo says public procurement documents show that companies held by Meszaros or his family won tenders to the tune of 486 billion forints (1.5 billion euros) between 2010 and 2017, with 83 per cent of the contracts on EU-funded projects.

In 2018, Brussels provided 93 per cent of the 265 billion forints (760 million euros) worth of public contracts he scored.

K-Monitor’s portal gives 22 red flags to the Meszaros es Meszaros Kft holding company, noting single-bid tenders and overpriced contracts.

Meszaros’s rail engineering group, R-Kord, has just three projects flagged, but together they are worth close to 100 billion forints (291.8 million euros). The g7.hu economic news portal estimates the cost of electrifying one kilometre of railway in Hungary at three times that in Poland.

The model is replicated at lower levels, run via the Fidesz party network, with help from Budapest-based consultancy companies that oversee applications and tenders. And the model is often surprisingly straightforward, independent lawmaker Akos Hadhazy told BIRN.

Based on information from whistleblowers, Hadhazy claims that Istvan Boldog, a Fidesz lawmaker from the rural Jasz-Nagykun-Szolnok county in central Hungary, has demanded that local mayors give contracts on EU-funded projects to a trio of companies: Profiter, Szalaibau and Akviron. The website of Hungary’s Public Procurement Authority lists numerous tenders awarded to the three firms.

Boldog did not reply to BIRN’s request for comment.

Mayors who objected were told their municipalities would get no funds and were personally blackmailed to boot, Hadhazy said. But he worries that the trail takes a twist when it gets to Polt.

Responding to questions from the MP, the chief prosecutor said in a letter sent in September and seen by BIRN that his office was investigating.

Three months later, in December, Petra Feher — Boldog’s right-hand woman — was arrested, along with the bosses of the three companies. She remains in custody. Prosecutors say they suspect Feher of profiting illegally from unlawfully awarded public contracts. However, Boldog is still an MP.

‘Agrofertisation’

In the Czech Republic, Prime Minister Babis worked the other way around to Orban.

The billionaire already had a business network consisting of the 230 companies operating in agriculture, food and chemicals that make up the Agrofert Group. In 2011, he launched his bid to add political power to that economic heft with a promise that his newly formed ANO party would clean up corruption.

However, accusations of abuse of EU funds have dogged his political career. Since winning the 2017 election, fraud charges over a two-million-euro EU subsidy claimed for the Stork’s Nest leisure resort have compromised his ability to govern.

With mainstream parties refusing to work with a prime minister facing potential criminal prosecution, Babis has been forced to work with the extreme-left Communist Party and far-right Freedom and Direct Democracy party.

That arrangement is orchestrated by President Milos Zeman, a wily populist known for his rhetoric against migrants and Islam, journalists and liberals. Critics also accuse him of seeking to undermine pro-Western policy in Prague and Brussels by forging links with Russia and China.

Two days after Czech police recommended in April 2019 that Babis be prosecuted, Marie Benesova — an old ally of Zeman’s — was suddenly parachuted into the role of justice minister.

She refutes claims that she might interfere with the independence of the prosecution but is pushing efforts to reform many parts of the judicial system, including the appointment of prosecutors.

In September, the lead prosecutor in the Stork’s Nest case, who had overseen the investigation for four years, caused surprise when he announced he would not press charges. The country’s chief prosecutor will now make a final decision.

A presidential pardon could be Babis’s get out of jail card. Zeman’s efforts to use that leverage sparked a crisis that paralysed the government throughout the summer of 2019 and threatened to push the Communists and SPD into formal government.

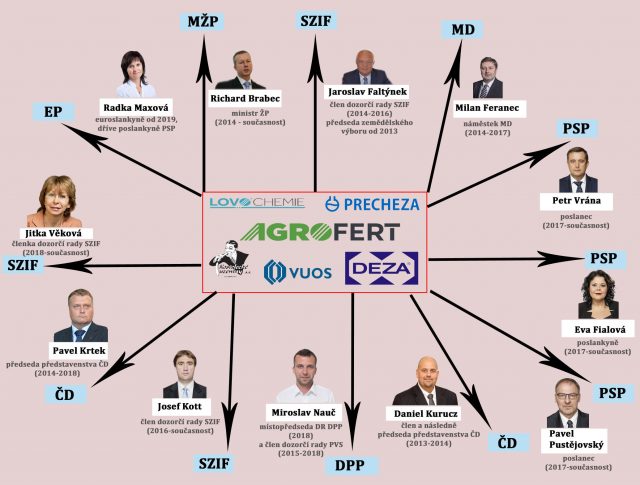

While many of the Czech Republic’s democratic institutions remain relatively robust and independent, the government and many of its agencies — as well as state companies — have begun to resemble a division of Agrofert Group, critics of the government say.

Many ministers, regulators and officials at state companies have Babis’s company on their resumes.

Petr Fojtek, a researcher for the Pirate Party, calls it the “Agrofertisation” of the Czech state administration.

The most senior ANO officials oversee the departments that control subsidies most important to Babis’s agrochemicals conglomerate: Richard Brabec at the environment ministry (MZP) and Jaroslav Faltynek at the State Agricultural Intervention Fund (SZIF).

The conglomerate is understood to have been absorbing millions in EU subsidies for years, although an exact figure is difficult to establish.

Babis’s office did not respond to emailed questions about whether the high number of former Agrofert managers drafted into the Czech state administration has helped ease the company’s access to EU funding.

A recent investigation by the New York Times claims the company drew the equivalent of $42 million (38 million euros) in farm subsidies in 2018. The investigation also focused on suspected land grabs and EU subsidies abuse in Hungary, carried out by Orban’s network.

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is the biggest ticket item in the EU budget, accounting for around 40 per cent of the total.

It is also an extremely sensitive area for member states across the bloc, meaning there is little enthusiasm to tighten up oversight, despite long-standing criticism that most of the money ends up in just a few large hands.

In Slovakia, Czechia and Hungary, more than 85 per cent of direct payments based on acreage to farmers goes to the top 20 per cent of recipients, according to Agriculture Atlas, a collaboration between the Heinrich Boll Foundation, Friends of the Earth Europe and BirdLife International.

From 2020, member states will have more room for manoeuvre in deciding how to spend CAP funds.

More than eight billion euros has been available to Czech farms in the 2014-20 budget period, according to European Commission data. The ministry of agriculture, led by long-time Zeman ally Miroslav Toman, is also petitioning the European Commission to allow it to divert higher subsidies to larger companies.

The Czech agriculture sector is dominated by bigger farms, a spokesman for the ministry of agriculture said, adding that “member states should be allowed to decide on some elements, such as [the] capping of direct payments, according to their national specifics”.

However, at the same time that the ministry is pushing for the freedom to channel more cash to the likes of Agrofert, the EU is finalising reports, the leaked drafts of which found that Babis has conflicts of interest in relation to cohesion and agricultural funds paid to the company that he put into trust in 2017.

Brussels has reportedly recommended that subsidies to the company be halted and could demand the Czech government return 451 million crowns (17.5 million euros) paid to Agrofert in investment subsidies since new EU conflict-of-interest regulations came into effect in 2017.

Mikulas Minar, one of the student leaders of a series of massive protests in 2019 who accuse Babis of damaging democracy to protect himself and Agrofert, worry that any money returned to Brussels “will not be recouped from the company, but be taken from the taxpayers’ pocket”.

A second audit into the roughly 6.5 billion crowns (250 million euros) paid to Agrofert under CAP since 2012 is underway.

However, the ministries of agriculture and environment both say they will continue to pay such subsidies to the company.

“There has been no formal process to stop the payment of subsidies,” Wagenknecht, the Czech Pirate Party senator, said. “The Commission only sent a request. It should step up and make sure the subsidies are really stopped.”

Loyalty as currency

These systems of corruption become self sustaining, analysts say.

To maintain them requires political power, and that is helped by the clientist networks of partners sharing the proceeds, which often wield financial and political influence at local levels.

Controlling the distribution of billions can earn a lot of political loyalty — the currency of authoritarian systems — and the differing mechanics of distribution has had specific effects on democracy across Central Europe.

Although somewhat centralised now, the distribution of EU funds in the Czech Republic was once extremely regionalised. Twenty-four agencies set out to disperse money in 2004, opening opportunities across the country at regional level.

“To have a chance of getting at EU funds you needed good relations with the local political godfathers,” said David Ondracka director of Transparency International Czech Republic.

He was referring to the system of political patronage that operated within the Social Democrats and centre-right Civic Democrats, the mainstream parties that dominated Czech politics until recently.

Putting huge funds into the hands of these local party bigwigs increased their sway, moving power away from the party centres. The most notorious region for scams was the northwest of the country, around the decaying industrial city of Usti nad Labem, close to the German border.

Wagenknecht audited some of the region’s councils in 2011. “It was very dark in there,” he said with a grimace. He said that 10 billion euros of 18 billion euros in EU funds paid out in the region to 2011 were manipulated.

The corruption scandals that emerged from these regional fiefdoms helped decimate support for the mainstream parties.

This offered Babis — who, like other larger oligarchs, had tapped EU funds to entrench his position and push aside smaller rivals — a political vacuum he was only too happy to fill.

“In this sense, EU funds helped create the space for populism,” said Ondracka from the Czech branch of Transparency International.

Sole gatekeeper

In Hungary, watchdogs say Fidesz has exploited the highly centralised distribution of subsidies to make itself the sole gatekeeper, controlling the system even at a very local level via its party network and the regional institutions.

“The main agencies clamped down hard on small scale corruption by others,” said Sandor Lederer, CEO at K-Monitor. “Everyone now needs permission from the party to steal. Fidesz doesn’t like to share.”

That goes for everyone, said Tamas Bodoky, editor-in-chief at Atlatszo. When Fidesz returned to power in 2010, it tore up a rule book that had long seen political parties of all shades share ill-gotten gains.

According to the Slovak consultant who helps municipalities with tenders, that puts Hungary in a league of its own.

“In Slovakia, EU fund corruption has always just been business,” he said. “No one cared what political party you came from. In Hungary it’s very different.”

The loss of this revenue has crippled the opposition parties and their ability to challenge Fidesz. The ruling party has used the extra cash to buy up the country’s media, which is key to Orban’s exceptional political strength, Hadhazy said.

Bodoky noted that mainstream media rarely report on corruption cases, meaning most Hungarians never hear about them. However, even those who do may not care.

Independent Hungarian lawmaker Akos Hadhazy holds up a sign saying ‘He has to lie, because he stole too much’ as Orban speaks in parliament.

Many in the region believe all political forces are corrupt, observers say. The cynicism has become so deep that corrupt practices can even be an advantage for politicians.

“Forty years of communism made corruption acceptable, and even admirable, in Slovakia,” Soltesz said.

This has helped promote the recent wave of populism, he added. “People know they won’t get a piece of the pie, so they want it to go to the guy that will hurt the people they hate most.”

Bodoky said: “Orban has stated he aims to build a national capitalist class. He persuades people that it’s better that these funds go to these Hungarian ‘entrepreneurs’ than international companies.”

Bogeyman

At an EU summit in mid-October, member states bickered over the bloc’s budget for 2021-2028, a process of negotiation expected to extend well into 2020. Negotiations continued this month at a Special European Council summit in Brussels.

Under current proposals, the three countries stand to lose billions in funding. Hungary and the Czech Republic would receive 24 per cent less than they did in 2014-20, leaving them with 17.9 billion euros and 17.8 billion euros, respectively.

Ahead of the October meeting, Visegrad Group countries — Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia — criticised the Finnish presidency of the EU Council for “fail[ing] to be an honest broker”.

Finish Prime Minister Antti Rinne had just suggested on a trip to Budapest that linking EU funding to the rule of law was widely supported. The motion had been gaining traction over the past couple of years as Brussels struggled to deal with rule-of-law concerns in Hungary and Poland.

Mesterhazy, the senior official in Hungary’s opposition Socialist Party, met with Rinne during the trip. But he is sceptical about the conditionality plan.

“Who defines the ‘rule of law’?” he said. “On the surface, Hungary meets the conditions better than Finland in many cases.”

He predicted that the idea will quickly get bogged down in such arguments.

On the one hand, EU funds are viewed as the only palpable point of leverage that Brussels has to prevent the erosion of democracy in member states.

On the other, the idea risks resembling a public relations exercise designed to appease the concerns of Western European taxpayers that they are funding corrupt authoritarian regimes.

Some media reports suggest Germany’s net contribution to the EU budget could more than double to 33 billion euros annually by the end of the next budget period.

Yet the EU has few options to clamp down on corruption.

Calls for the bloc to stop funding illiberal regime by halting all subsidies are not uncommon, but most commentators BIRN spoke to stressed that EU funds still do a lot of good in the region.

EU money has helped economies, infrastructure, innovation and the environment over the past 15 years, they said, and there is plenty more to be done as Central and Eastern European states push to catch up with those in the West, despite common claims that the net payers benefit even more.

Since they began receiving EU funds, “all four Visegrad Group (V4) countries have reported dynamic social and economic transformation, which largely helped to bridge the development gap between those countries and the EU average,” says a recent report commissioned by the Polish Ministry of Economic Development.

“This is attributable to many factors such as the global benefits of having open borders, participating in the single market or the inflow of foreign direct investments,” it continues. “However, the social and economic change in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia is also largely due to the impact of operational programmes funded under the Cohesion Policy.”

The report’s authors note that cohesion funds have boosted gross domestic product levels across the region.

In Slovakia, Sybila from Progressive Slovakia — who hopes a coalition led by his party can throw SMER-SD into opposition in a general election on February 29 — says it is important that Slovakia continues to receive funds to help its development, but the system needs to be refined.

He said he would like to see less money handed over by the EU. “Then the ministries would need to compete for it by putting forward good projects. Now they just seek to absorb as much as possible.”

Others, like Hungarian lawmaker Hadhazy, hope the newly established European Public Prosecutor’s Office could help by pursuing cases put forward by OLAF but ignored by national authorities. Hungary, however, has declined to sign up.

Lederer at K-Monitor also insisted that EU funds are still valuable to the region’s development. However, he said that limiting their use to large, state-run infrastructure projects would help.

Wagenknecht of the Czech Pirate Party agreed, but said he would also like to see small and medium-sized enterprises benefit from support.

“EU subsidies to larger companies are clearly distorting the market,” he said. “It’s not just Babis and Agrofert; we have other ‘families’.”

Such a move would run counter to Babis’s bid during negotiations on the 2021-27 budget to win greater freedom to decide how to use funds, and any crackdown would only add grist to the mill of the region’s populist governments, who have made Brussels a bogeyman that seeks to dictate.

Others point to political obstacles inside the EU machine.

“The EU rules are vague, and lack the needed definitions,” said NFPK corruption investigator Skacha in Prague. “The priority, even for Brussels, is simply to get the money spent. If they were to crack down there would be problems across the EU, not just in this region.”

Homework

Most commentators, however, put the onus on the national governments.

Slovakia is one country that has made some progress in tackling corruption despite a slew of high-profile cases. Transparency International ranked it 57th out of 180 countries in its latest Corruption Perceptions Index, down from 66 in 2011.

“It’s a different game at state level, but it’s all tightened up at regional level,” the Slovak consultant said.

Transparency is key. There is no easily searchable official database of EU funds in Hungary or the Czech Republic. Although some information is available via public procurement portals, complex ownership structures can obscure the ultimate beneficiaries. The European Union also provides no single database.

But in 2011, Slovakia launched the Central Register of Contracts, where all public contracts are required to be published.

“This regime makes Slovakia one of the most transparent countries in the world in many ways,” said Sipos of Transparency International Slovakia.

But transparency on its own is not enough, the watchdog NGO cautions in a recent report. That information must be worked to make getting caught a palpable risk.

“Scrutiny of contracts is linked to the freedom and professionalism of local media and NGOs,” the report says. “And not least, naming and shaming stemming from revealed contracts can lead to change only if public officials are responsive enough to take responsibility for their actions.”

This system is starting to work at a regional level, the consultant said. “No one dares to try to abuse the system now. They’ve become very wary of getting caught over the past three years or so.”

Sipos suggested the government should try to push the consultants out the process by helping municipalities identify projects and apply for funding. The consultant, however, said there is now even more need for expertise such as his.

“The worry amongst administrators is now so great, and the system has become so complex, that companies and municipalities are put off applying for projects at all,” he said.

That means that the savings are few.

“The money saved from the lack of corruption now goes to expensive consultants like me,” he said with a smile.

Transparency International’s Ondracka noted that a similar tightening is underway in the Czech regions.

Additional checks and audits, further centralisation of the system and a number of high-profile prosecutions have removed the sense of immunity, and now “prevent the simplistic and blatant fraud that was operating in the regions”, he said.

However, it is harder to effect change higher up the food chain.

In Prague, the NFPK’s Skacha said he expected to be busier investigating corruption in coming years, suggesting the efforts of Zeman and the Communist Party to strengthen links with Russia may pose risks in the energy sector.

All three Central European countries are working on new nuclear power capacity. Those are projects that will send further billions sloshing through the system.

The Czech Republic plans to spend up to 40 billion on new units by the middle of the century. Babis said in October that his government was ready to “breach European law” to get the first underway.

Russian state nuclear agency Rosatom is a leading contender to build the new capacity. It has already clinched the expansion of Hungary’s only nuclear plant, Paks. The project is driven by a 10-billion-euro loan from Russia.

The nuclear drive will bring another wave of cash, agrees Mesterhazy, but he noted that Orban has also been trying to line up China as a source of even greater funds.

“China has a lot more money than Russia,” he said. “And unlike EU funds, it comes with no strings attached. They don’t care it it’s spent, stolen, whatever.”

Only a significant shift in political power can stem the corruption that is undermining democracy in Hungary, he added.

The potential for that is some way off. Orban retains a tight grip on Hungary’s government and democratic institutions.

However, opposition parties recently won control of several major cities, including Budapest, in municipal elections. The new mayors have pledged to immediately start digging into suspected corruption. Fidesz’s network may be seeing its first cracks.

This story was produced with a grant from Reporting Democracy, a cross-border journalism platform run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.