The Straits Philosophical Society And Colonial Elites In Malaya – Book Review

Introduction

The third quarter of the nineteenth century is exciting in its own way with stories of the interplay between the consequences of the Peace of Westphalia, the rise of nationalism, ethnocentrism, and fascism in Europe, of Communism that was beginning to take root in Russia and next, China, and of the civilizing mission of the colonizers as they impact how the natives were enslaved or turned into indentured or debt-bonded serfs are to be governed,

As it concerns British imperialism in general and Malaya and Singapore in particular and as this review is about, it illuminates how Philosophy serves the purpose for giving direction to the ideological and discursive dimension of understanding the mind of the natives and the colonial migrants as they exist in the colonies. In Singapore, one of the earliest colonial outposts, the work of The Straits Philosophical Society, albeit brief, provides an excellent salon of ideas of colonial management. The members discussed race, identity, and the colonial project, at a time when Structuralism was the dominant paradigm of looking at scientific and social phenomena and Social Darwinism was emerging as a popular lens for looking at the evolution of societies.

Almost a decade ago I was made aware of this work on Colonial History by one of Asia’s most prolific social scientists, Lim Teck Ghee who conceived it as a commentary of essays, and today after almost fifty years the much-awaited collection of the writings of the colonial elites of The Straits Philosophical Society had come to elegant fruition. The volume is an admirable academic labor of love that began with Lim Teck Ghee’s 1976 discovery of a set of “about to be-discarded” unpublished philosophical papers in the Penang State Library and how this prominent Malaysian historian salvaged the valuable set of 17 papers.

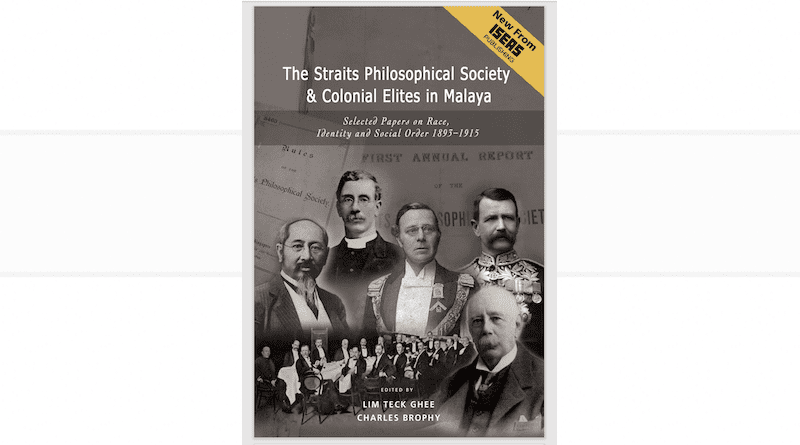

The result is a collaborative effort with a British-based prolific editor and scholar in Colonial History, Charles Brophy to produce this volume of work on the commentary of primary sources of the work of the Straits Society. The Institute of Southeast Asian Studies publication of Lim Teck Ghee’s and Charles Brophy’s The Straits Philosophical Society and Colonial Elites in Malaya: Selected Papers on Race, Identity, and Social Order 1893-1915 is timely, especially for academics and students of Southeast Asian History interested in understanding the philosophical debates that were happening in late 19thCentury Singapore and Malaya. This 462-page book consisting of thirty essays should be a delight to those interested in political philosophy as it pertains to British colonial history. As an educational contribution to the field, this book offers us a glimpse of the value of philosophical thinking in developing perspectives on the inner working of colonialism, offering a range of critical themes, from the basis of colonial ideology, the psychology and political economy of the Straits Chinese, the impact of the Opium War on the Chinese in Malaya, to the extensive narratives on the colonial construction of Malayness.

This review essay concerns not only the educational value of the work of Society today but also the debates on how the colonies should be governed for maximum return taking into consideration race, religion, and ethnicity of the colonized.

Core argument

The quote below exemplifies the essence of the work I am reviewing: the transcultural flow of ideas especially at the time of de-colonization:

” … Nevertheless, beyond the model of the philosophical society the Society represented, the ideas propounded in the Society can also be said to have had far-reaching consequences beyond its life. The mixture of ideas around liberalism, Darwinism, colonial modernity, and race, constituted the basis for a dominant ideology in colonial Malaya, centered on the necessity of European modernization, a critique of liberal ideas of empire, the protection of native races, and the racial distinction between Europeans and Asians. Yet as the Society also evidenced, this schema also contained its own tensions—tensions which were played out in the

presentations and critiques of the Society. More importantly, in opening a space for non-Europeans to engage with colonial thought, the Society also made possible its appropriation and modification and, as in other colonial learned societies, contributed towards the development of an independent intellectual culture in British Malaya, developing around ideas of nationalism and national modernity. This engaged not only with transnational flows of nationalist and modernist thought in the colonial world but also formed the basis for early nationalist thought and development in the Malayan Peninsula ” (Lim and Brophy, 2023)

Looking at the Straits Philosophical Society from the perspective of critique of ideology (ideologiekritik, as Jurgen Habermas would say,) I see these contending ideas of society and how it should evolve through political will and practices of the “strong State,” (based on command economy and authoritarianism,) there is a dialectic tension of the march of the history of ideas. What revolutionary leaders or political elites learned from the former colonies is not merely how to continue to subjugate the colonizer/natives through realpolitik but more long-lasting is the process of being educated on the contradictions of colonial rule. For example, what Ho Chi Minh learned while he was in exile in England working in a restaurant washing dishes, Mao Tsetung learned in Russia, and Ahmed Soekarno learned from the Japanese vis-a-viz Dutch colonial rule are about the realization that ideas that are foundational to colonialism and empires are also challenged especially by liberal philosophers.

The work of what is human nature vis-a-vis how power is to be exercised is brought into the ongoing debates in the drafting rooms of power in the Centers that control the Peripheries if we frame it from the perspective of World-Systems theory. The work of Rousseau, Voltaire, Erasmus, Locke, and humanists (and of the radicals of the Enlightenment Period as well,) inspire the leaders of independence movements. Gandhi’s readings of Henry David Thoreau and German transcendentalists for example gave the ammunition for the “satyagraha” (non-violent movement) of pre-independence India.

Going back to the work of the Society, as documented and critically analyzed by the commentators Lim Teck Ghee and Charles Brophy, the forum is perhaps inspired by Madam Pompadour’s-patronaged-French salon of the 18th. century, only that it provides a space not to talk about bringing down colonialism or guillotining the king of England to bring down British imperialism, or doing a Maximillian Robespierre-type pro-Monarchy cleansing but how to colonize and enslave the natives of Malaya and Java, gently as well as how to define their racial identity in a scheme of colonial divide and conquer and plunder. In the case of the work of the Straits Society, it is still a circa World War 1 forum that would eventually ignite interest in post-World War II independence/de-colonization movements.

Exemplary, in this fine collection are the contributions of colonial elites such as H.N. Ridley, William J. Napier, David J. Galloway, Tan Teck Soon, W. R. Collyer, Gilbert E, Brooke and W. G. Shellabear among other Straits philosophical luminaries, on the colonial project, on the Malay race and Malay identity respectively, as they pertain to how to manage and advance the Malays and the interest of the British empire.

As many a student of Malay History and studies would know, H.N. Ridley was instrumental in bringing rubber seeds into Malaya and turning its product into an economic enterprise for the British empire, at the time when the American automobile industry was in its infancy, and W. W. Shellabear was a scholar who wrote important analyses about Hindu-Buddhist influenced Malay literature.

What is fascinating about this collection is not only topics such as the debates surrounding how to govern the colony and the Chinese Straits community especially in Singapore within the context of the Opium War, gang membership, and the way they are governed but also the lengthy and numerous thematic discussions on the nature of the Malays, their religion, and how the “people of the land” (today called the Orang Asal or the Bumiputeras) responded to the advent and subsequently the subjugation of the British colonials. The debates by the members of the Straits Philosophical Society of the early 1900s are epistemological and anthropological in nature, focusing on how the colonizers ought to understand whom they are colonizing, especially when the latter had already an established system of being governed: of the “kerajaan”. The debates are fascinating as they also demonstrate how the members engage in the process of “Othering” to facilitate the process of enslaving the body, mind, and spirit of the natives. Hence, they entered the realm of exploring and defining the Malay psyche namely the nature of the “Mohammedan-ness of the Malays”, the psychological phenomena of “amuk” and “latah” and what these people are prone to do under the colonial system of reward and punishment.

Lim Teck Ghee and Charles Brophy, in their analysis and critical review/Introduction to this valuable volume of high scholarly work on Colonial Malaya, did a superb job of analyzing the interplay between the Chinese immigrants, the Malays, and their protectors (the sultans) and the colonials themselves shedding light on how to look at the complexities of race, religion, and royalty in Malaysia today.

Contrasting worldviews on managing the colonies

Reeling in my mind, as I read the essays and the intellectual construction and representation of the members of society, particularly of the identity of the Malays for example, are the questions: Where were the Malay scholars while these debates were happening? Why wass there no one from any of the Malay royal court households when the fate of Malaya and the construction of the identity of the Malays were discussed? I had a hypothesis, presented below:

The Malay Rulers of the 1800s, at the time of Dutch and British colonialism, were not intellectually equipped enough to debate and dialogue with the members of the Straits Philosophical Society perhaps for the obvious reason that Western philosophy and anthropological zeal are the forte of colonialism.

Borrowing Machiavelli’s idea in The Prince, one must have control over matters in order to have the power to administer things. The Western intellectual tradition has evolved over centuries in crafting the notion of how the “West” view the world. Even from the time of Athens in the fifth-century B.C, Alexandra of Macedonia was trained in thinking “scientifically” in Plato’s academy. In the case of Malay society, the essential tension is clear as an intellectual trajectory of history, something which is not evident in the evolution of the Malay mind. The Malay rulers are not the embodiment of ideologies that advance scientific and philosophical inquiry. Therefore, the cognitive ideological tools and techniques to fight against colonialism were not present and thus nurtured, let alone cultivated the ability of the people to translate ideas and innovations into techniques to produce advanced military strength to protect the Malay kingdoms is not cultivated. We saw that in the fall of Melaka in 1511.

Elaborating on the notion of poverty in philosophizing above, Western philosophy and technology proved to be superior to what the Malay rulers possessed. Lacking is the culture of thinking and inquiring and creating newer, most necessary, and advanced technologies to stop or slow down the advancement of colonialism. This is understandable from the point of view of intellectual history — the Malay Rulers did not experience the Copernican Revolution, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment Period, The Scientific Revolution, and later the First Industrial Revolution that produced engines and change and tools of empire. They were preoccupied with maintaining their kerajaan, or kingdoms through psycho-spiritual means and symbolism of cultural-religious grandeur.

The Malay Rulers were not equipped, or rather, failed to equip themselves, with that vast array and arsenal of intellectual heritage. The evolution of literacy, technology, and ideology did not favor the Malay world. What they had, even from the time of the Melaka kingdom is the loose concept of “daulat” and “kerajaan” as tools to glue enclaves and pockets of society in some form of concentric-styled loose entity of social control, as many a historian of Southeast Asian politics such as Harry Benda, William Roff, and The Andayas would analyze. The daulat, or the conception of control based on the claim of the “divine right of the ruler sanctioned by Allah (God in the Muslim religion) is used as an abstract concept popular in the histories of monarchies.

The Malay monarchs, even if they were involved in the contending discourse or the debates on the dialectical-materialism of things entire, in regional and global colonial politics, their preoccupation revolved around the involvement in one case of the Johor sultanate in World War I: how to save the kingdom from the wrath of the British and the Dutch and the Central and Allied Powers by positioning and repositioning oneself with the Ottomans and the Germans and to then switch alliances, in a complex mix of the survival strategy of global politics. This above note of the lack of philosophical reflection warrants a separate discussion.

Discarding Philosophy in Malaysian academia

In the first few paragraphs of this review essay, I mentioned the genesis of this project by Lim Teck Ghee, of how these philosophical papers were about to be discarded by the university library. I find this metaphoric of the state of affairs of especially Malaysian academia today. The death of Philosophy and Critical Sensibility after being discarded by the post-Tunku Abdul Rahman’\s decades of Malay-Muslim hegemony and the constant attack on the word “Liberalism” and consequently any attempt to bring about the teaching of Liberal Philosophies in the classrooms and into the minds of the students fed by the ideologies of “Mahathirism.” an admixture of half-baked understanding of free enterprise and Malay nationalism whose state is governed via Soekarno-inspired “guided democracy.” As in the metaphor of the “Butterfly effect of things” in History in which events and consequences follow the pattern of chaos, order, and randomness, so is the metaphor of the discarding of these philosophical papers that today, signifies this nation’s failure to develop a thinking citizenry. Perhaps the Malay-Muslim Islamization agenda has developed the perception that these papers are to be discarded because they are borne out of Western Liberal ideas. I elaborate on this proposition below.

What is the value of this collection of critical review of primary sources in the early conceptualization of British colonial rule viz-a-viz the work of the Straits Philosophical Society?

What can we conclude from the 100 years of the evolution of thinking in fact, in Malaysian or even Singaporean academic circles as it relates to writing that critiques dominant ideologies? Here are some thoughts:

- Over the decades the constant lamentation in academia has been that there is no academic freedom given in our universities and since the time Mahathir Mohamad took over in 1981 as prime minister, acts such as the University and University Colleges Act of 1971 (UUCA) and its instrument of intellectual oppression the Academic’s Pledge of Loyalty (to the ruling regime,) had discouraged the development of critical sensibility. Even today, as current, as this review is written, the new Minister of Higher Education has pledged that there will not be a revision to the Act since it is still useful for the new government to control the universities,

- The continuing rise of Malay-Muslim influence in all spheres of life and governance since the “Islamization Agenda” of the Mahathir-Anwar administration, has institutionalized hegemony of this nature, destroying the urge and necessity for the educational institutions to teach subjects such as Philosophy or Critical Thinking or those in the field of Liberal ideas, thereby closing the Malaysian mind from an in-depth exploration of profound ideas of the Western world,

- The policy of de-emphasizing the use of the English Language in all educational institutions, especially in the refusal to teach Mathematics and Science in English, has created perhaps now two generations of students and also governmental leaders with command of the language low enough to master the complexities and rigor of understanding and mastering philosophical thinking useful for the advancement of society.

Those are among the few observations I made on the death of philosophizing in Malaysia today, in relation to the work of the Straits Philosophical Society.

How to read this book

The Straits Philosophical Society and Colonial Elites in Malaya is essentially a book on philosophical ideas pertaining to colonial rule in British Malaya, a fascinating read if one is interested in Philosophy in general and Political Philosophy in particular. The Straits Philosophical Society established at the end of the 1800s was a forum to intellectualize the directions and inner workings of the empire, especially on issues of race, identity, and the economy. Pedagogically, how do we read this collection of essays and commentaries then if we are to use it to teach Colonial History?

In my decades of teaching, amongst other subjects/courses such as United States History. Ancient and Modern World History, Colonialism, and Imperialism, and even currently in Human Geography and Sociology of the Future I would use primary sources as the main texts to analyze phenomena and patterns in History. I’d asked students to read first-hand accounts, treatises, letters, and journal entries, and analyze visual text such as photos and other similar forms of representations.

Although students might have a difficult time reading works such as those written in “archaic English” they will be encouraged to persevere. I’d guide them through the language usage and most importantly the content.

Thus, reading Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, Plato’s Dialogues, Symposium, Meno, or translated texts of the Enlightenment Period such as Voltaire’s Candide, Rousseau’s Emile and essays and discourses on equality and human nature, or even “reading paintings” such those by the French master Jacques Louis-David and his visual commentaries on the French Revolution (housed primarily in the Louvre in Paris,) may be challenging but necessary.

The essays in this collection on the philosophical discourse concerning the Straits Settlement and, on the economy, the “civilizing mission of the British Empire, the Straits Chinese, and the Malays I suggest must be read in the following sequence:

First, read the primary essays

Next, read the counter-arguments

Lastly, read what the authors/compilers have to say.

I value original thinking in my students. The key question is “What do you think? How do you support your claim?” after ensuring that they understand what they have read, have them summarize the contents and explain the author’s idea, in the student’s own words. This is the process of reading I have been using since I started teaching. It is a metacognitive process of close reading, contextualizing text, and context and hypertext so that there is a sense of “heteroglossic” understanding of what one is reading. Complex is the idea or reader-response to the text since our reading will always be subjective and culturally bound and governed by a multiverse of experiences we bring, in the process of interpreting.

I want to create philosophers out of my students. I have no answers for them. This has been an aspect of my philosophy of teaching that has kept me passionate as an educator, academic, and student of humanist praxis and complex systems in general. Hence, the suggestion on how to use the book as an enrichment material on Colonial Malaya.

Conclusion

Lim Teck Ghee’s and Charles Brophy’s must-read work in commenting on the primary sources of political philosophical ideas pertaining to race, identity, and governing the Malay colony is both valuable as an analysis and a classroom text to teach about colonialism and the construction of colonial identity. The Straits Philosophical Society and Colonial Elites in Malaya is an elegant work in its own class of originality given the fact that these papers were about to be discarded. The value of the collection of excellent essays, written circa 1895 to 1915 lies in its nature as the primary source, which historians and teachers of Colonial History especially would appreciate using in class. Even more valuable is the nature of philosophical arguments crafted and debated in the style of Marxist dialectics concerning how the colonies, especially Malaya and Java are to be governed.

The British and Dutch ideologues at times illustrated in the essays have differing conceptions of human nature, the interpretation of worldviews, on race and identity, of Malayness, and how human labor in the colonies is to be managed. One must give credit and even show admiration for the members of the Straits Philosophical Society for bringing philosophical perspectives to the study of colonizing. Aside from the idea that colonialism is evil and that for example, the British Empire siphoned trillions of dollars from the continent and make millions suffer, one must get to the root of the analysis of the anatomy and chemistry of colonizing strategy itself: what role does philosophy and anthropology play in structuring the intellectual strength and rationale for subjugating and enslaving “the little brown brothers”, to advance the civilizing mission of the empires? To capture and control resources in the name of the Cross and in the context of the Crusade, and finally to hold on tight to the often-quoted (or misunderstood) line from Rudyard Kipling’s poem “Mandalay” East is East, West is West and the twain shall never meet?

The world of Western intellectual progress circa the late 1800s to mid-1900s produced a systematic and universalizing view of human nature and social order vis-a-viz colonialism, of raw Structuralism, I’d say, founded upon race superiority and the advancement of empires as the highest stage of “colonial and mercantile” capitalism, as Vladimir Lenin analyzed in his famous essay.

Lim Teck Ghee and Charles Brophy’s work The Straits Philosophical Society and Colonial Elites in Malaya is an elegant invitation to the foundational debates of colonialism of the day circa World War I. As elegant as the Nobel Prize novel by Kazuo Ishiguro on a World War II theme, The Remains of the Day.

The professional–and even anecdotal– literature on colonial elites and power structures is lean and scattered. There is no equivalent of, say, of C. Wright Mills’ Power Elite (the US) and elite studies of that vintage (Dahl, Agger, Swanson et al. and a small cluster of other similar published, peer reviewed studies. The distinguished Lim Teck Ghee’s published study (with his colleague Charles Brophy), Colonial Elites in Malaya, is, I hope, a trend setter. It breaks ground long overdue for being broken. Elite and power structure studies lay bare how power is deployed, what interlocking elite structures (particularly the informal ones) work and, inter alia, who gets what, when and how in real life politics. This study bears out once again, senior author, Lim Teck Ghee’s crisp, clean, erudite and comprehensive grasp of subject matter aided by Brophy’s, apparent, considerable assistance. I recommend it to the next generation of scholars and those of ours. It ought to be required reading–subject matter that should excite our curiosity, whets appetites for discussion, debate and critical, balanced evaluation. Colonial Elites in Malaya widens the bandwidth in which our common colonial heritage (such as it is) is ensconced. This new text invites us all to think anew about much hitheto taken for granted and accepted uncritically at face value. I recommend it without reservation, unconditionally and with warm enthusiasm.