Syrian Rebels Capture Idlib – Analysis

By Syria Comment - Joshua Landis

By Aron Lund*

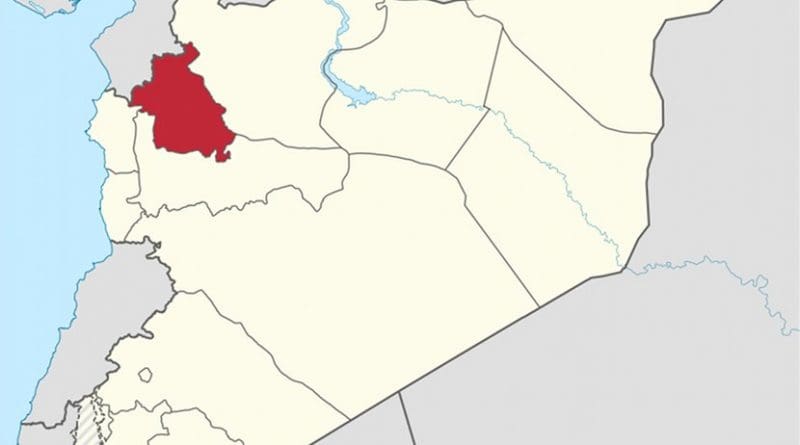

On March 28, Syrian rebels and jihadi fighters announced that they had captured the city of Idlib, posting pictures and videos online that showed them in control of government buildings and other landmarks. This followed a lightning offensive of several days, by a coalition of Sunni Islamist militias that assaulted the city from several directions.

After the security forces of President Bashar al-Assad violently put down protests inside the city in 2011 and 2012, resistance had been relegated to the countryside. With most of the surrounding Idlib Province captured, rebels had in the past year slowly but surely increased pressure on the city itself. They repeatedly demonstrated their capacity to block access roads as a way to force concessions and prisoner exchanges, which must have been a demoralizing experience for pro-Assad forces inside the city. In December 2014, the bell tolled for Idlib City, when the opposition overran the long-besieged Wadi Deif base, freeing up hundreds of crack rebel fighters for new campaigns.

At the time of writing, the situation remains unstable and it cannot be ruled out that Assad’s forces will launch a counterattack from areas still under their control. The government-run SANA news agency only speaks of “repositioning forces” in the southern neighborhoods of the city. Still, the apparent collapse of government defenses in Idlib has punched a gaping hole in the government’s narrative of approaching victory and boosted the opposition politically as well as militarily, spelling trouble for Bashar al-Assad.

A Sign of Government Overstretch

Out of thirteen provincial capitals, Idlib is only the second to be lost to the government, after the northeastern town of Raqqa was captured in early 2013. And like Raqqa, Idlib is a regional center rather than a major city – it would not fit on a top-five list over Syria’s most important cities. But the blow is heavy nonetheless.

The government remains much stronger than any rebel group on the national level, controlling perhaps two thirds of the population. Assad’s semi-cohesive central leadership and his control of a fully functional air force makes him Syria’s by far most powerful political actor, but his regime suffers from serious shortcomings nonetheless. It lacks enough reliable troops to conduct multiple offensives while also controlling its current territory and has been forced to farm out sensitive security tasks to local militias and Iranian-backed Shia Islamist foreign fighters.

Meanwhile, the state-run economy is withering, with a currency crisis and increasingly debilitating lapses in the fuel supply system and electricity production. The falling oil price is likely to cap Russian and Iranian support at levels too low to sustain the current ambitions of their Syrian ally. In short, it seems that Assad is still trying to bite off more of Syria than he can swallow, and the recent defeat in Idlib underlines how dangerously overstretched his regime has become.

The Islamic Emirate of Idlib?

The fall of Idlib is not without its risks for the rebels. Previous attempts by opposition groups to govern urban areas in Syria have been disastrous failures. Of course, a major reason has been Assad’s systematic bombings of civilian areas and infrastructure, which have killed and maimed tens of thousands of Syrians and forced millions out of their homes – a treatment now likely to be extended to Idlib. Even so, the rebels themselves are far from blameless. They have by and large failed to produce anything other than chaos and economic collapse, with what they refer to as liberated territory now suffering from chronic infighting, predatory criminal bands, and the brutal imposition of ultra-conservative Islamist norms. Most infamously, Raqqa has since its capture in 2013 transformed into a local capital of sorts for the self-declared Islamic State.

In the case of Idlib, many different groups were involved and all of them are hostile to the Islamic State, but the offensive appears to have been spearheaded by jihadis from the al-Qaeda-aligned Nusra Front and the large Islamist faction known as Ahrar al-Sham. While there are important sources of friction between these two groups – Ahrar al-Sham refuses to endorse al-Qaeda’s anti-Western attacks and is seeking local allies to avoid being swallowed up by the Nusra Front’s increasingly bold bid for hegemony in Idlib – they are both overtly anti-democratic, hostile to religious minorities, and committed to establishing a Sunni Islamist theocracy in Syria.

There is already great concern in the United States and Europe over the riseof jihadi groups in Syria. Now, early headlines in the Western press speak of a city that has “fallen into the hands of al-Qaeda,” which is hardly the kind of coverage that Syrian rebels were looking for.

This will be a serious problem for the rebels in the coming weeks and months. If Idlib becomes the scene of public floggings and streetside executions of “immoral” women, such as the Nusra Front has committed elsewhere in Idlib Province, or if it collapses into a turf war between rival groups, it would not only weaken more moderate rebel factions – it would also provide Bashar al-Assad with an opportunity to turn military defeat into political gain.

Where Next?

Militarily, however, the Idlib defeat puts Assad in a difficult spot as he needs to foresee the next rebel assault and deploy accordingly. Rebels already controlled most of the Idlib Province, but some pro-regime pockets remained apart from the provincial capital – notably the twin Shia towns of Fouaa and Kefraya, near the Sunni Islamist-controlled town of Binnish to the northeast of Idlib City. On March 27, Ahrar al-Sham announced that it had cut the last remaining supply route via Idlib City to Fouaa and Kefraya, meaning that these towns will now have to sue for peace with the rebels or risk destruction and perhaps a sectarian massacre.

To the south of Idlib City, the government controls a string of towns in the northern Jabal al-Zawiya region, the largest being Ariha, that served to supply forces inside Idlib. If that is no longer an objective, the regime may decide to abandon some of them to focus on defending territory of larger strategic value. However, at the other end of the road controlled by Ariha, we find the city of Jisr al-Shughour which connects the Idlib province to the Sunni-populated and rebel-friendly northern areas of Latakia Province. While Jisr al-Shughour is of little value in itself, Assad will presumably be reluctant to allow for increased pressure on his strongholds on the Alawite-majority coast. According to some sources, the government transferred its provincial government offices from Idlib to Jisr al-Shughour already two weeks ago.

South of Jisr al-Shughour lies the Ghab area of Hama, a heavily irrigated agricultural plain that butts into the Idlib Province alongside the Alawite Mountains. This religiously mixed powder keg has seen fierce fighting and may be of particular value to some rebel groups – for example, many of the founding fathers of Ahrar al-Sham hailed from villages in the Ghab. It is also possible that rebels from Idlib could move further south past Khan Sheikhoun and the battleground town of Morek, thereby attempting to put pressure on Hama, Syria’s fourth-largest city. It is a Sunni stronghold that has remained under Assad’s rule but could prove difficult to control once rebels gather critical mass on its outskirts. A rebel advance on Hama would certainly force the army to concentrate forces there, even at the expense of other fronts.

To the east, there is another very attractive target: the Abu Duhour air base. Capturing it would not only hobble Assad’s air campaign, it would also open up an area of coherent rebel control from the Turkish border to the desert south of Aleppo. In so doing, the rebels would also expose Assad’s only remaining supply line into Aleppo, a desperately improvised logistics trail through the rural towns of Khanaser and Sfeira that would be tremendously difficult to defend against multi-pronged attacks, especially if air cover falters. Under that scenario, the rebels could turn the tables on Assad in Aleppo, threatening his control over the city by cutting it off entirely from the rest of Syria.

At the end of the day, however, Idlib City is of limited value in itself. It is possible that the regime will counterattack or that none of the scenarios sketched out above will materialize. But considering the military and economic resources invested by Bashar al-Assad in its defense over the past four years, the loss of Idlib would undoubtedly signal to many of his supporters that the government’s current strategy is untenable in the long term

*Aron Lund is a freelance writer on Middle Eastern affairs and the editor of Syria in Crisis, a website published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Affairs.