Kazakhstan: Political Party Reshuffle Hints At Arrival Of New Order

By Eurasianet

By Almaz Kumenov*

(Eurasianet) — Formal politics in Kazakhstan are more performance than substance. The merger of two parties this week, however, may have some real-world implications.

On April 26, the ruling Amanat party, which is the post-rebranding name of the ruling Nur-Otan party, held its 23rd congress and had lots of important news to share.

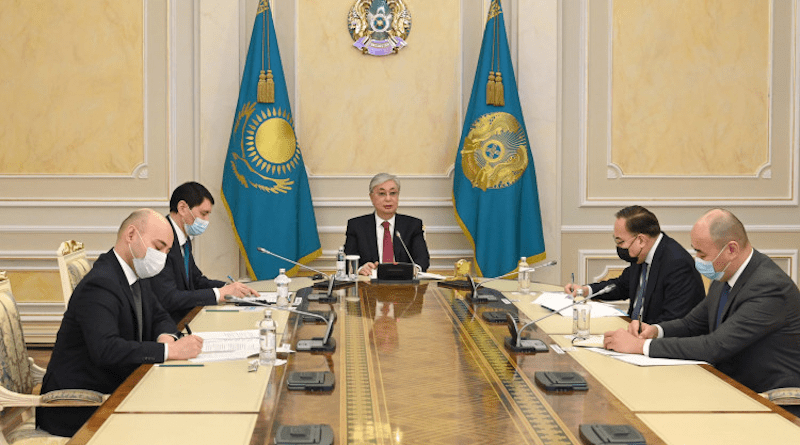

The first was that President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev will no longer lead the party. On paper, this is a marked departure from form.

Until earlier this year, the party was led by Tokayev’s predecessor, Nursultan Nazarbayev, who stepped down as president in 2019. (The very name Nur-Otan, Radiant Fatherland, was a transparent tribute to the former leader). But Nazarbayev was unceremoniously shunted out of the chairmanship job in the wake of the public unrest that broke out in early January, much of which was fueled by anger at his decades of crony rule.

But Tokayev doesn’t want the job either. He is all about what he calls “deep de-monopolization of all spheres,” meaning that he doesn’t want the executive branch to be seen as also dominating the political scene.

“I consider it expedient for the head of state not to give their preference to any party. In other words, they should be politically neutral. This is my unshakable position,” he said.

There is still room for some constitutional overlap, though. The new leader of Amanat will be Yerlan Koshanov, who is also speaker of the Majilis, the lower house of parliament. Koshanov is a former chief of staff to Tokayev and, accordingly, an uber-reliable ally.

Koshanov looks as close to Tokayev as the former speaker of the Majilis, Nurlan Nigmatullin, who resigned from the position on February 1, was to Nazarbayev.

The lingering whiff of Nazarbayev and his extended network of wealthy relatives and cronies is indeed behind much of this reorganization of the furniture.

In another congress-based development, it was announced that Amanat is poised to merge with another pro-government micro-party called Adal. The tie-up makes little sense at first glance. At the January 2021 election, Nur-Otan, as it was then called, got 71 percent of the vote, earning it 76 seats out of the total 98 elected posts up for grabs. Adal got 3.6 percent of the vote and not a single deputy.

But that doesn’t mean Adal is without influence. The founder of the party was none other than Nazarbayev’s own son-in-law, the billionaire Timur Kulibayev. Among his many perches, Kulibayev was until recently head of the Atameken National Chamber of Entrepreneurs, a business lobby with claws that were once deep in the flesh of the state. Key positions in Adal were held by figures from within Atameken.

Adal party secretary Eldar Zhumagaziyev sold the merger as a blow for national renewal.

“We are all builders of a ‘New Kazakhstan,’” he said, citing a term often used by Tokayev to describe his stated liberalizing agenda. “And we are aware of the need for further development of our party through consolidation with the country’s leading political force: Amanat.”

This is lofty but disingenuous rhetoric. The reason for this reorganization looks to be more influenced by electoral expediency than anything else.

Tokayev appears genuinely committed to creating the appearance – or possibly even the reality – of a competitive electoral scene. This is what he means when he refers to liberalizing the political system. In practical terms, this implies making it easier for new parties to register.

Merging with Adal, some believe, could give Amanat a solid head-start by providing it with a ready-made base of support among the well-monied entrepreneur class.

“Amanat is mainly represented by civil servants and state employees, and now there will also be many entrepreneurs in the party,” as Talgat Ismagambetov, a researcher at the Almaty-based Institute of Philosophy, Political Science and Religious Studies, told Eurasianet.

Once Amanat and Adal complete the merging process, the number of legally registered parties in Kazakhstan will shrink from a mere six to an even slimmer five. But other aspiring party builders are gradually emerging. News website Zakon reported last week on four parties known to be preparing the paperwork: El Tiregi (Pillar of the Nation), Halyk Derbestigi (People’s Independence), Namys (Honor) and Baiterek.

Ismagambetov is caustic about this semblance of activity, however. Amanat will continue to dominate the political arena, despite Tokayev’s promises of future competition among the parties, he said.

“Even when registration requirements for political organizations are eased, the authorities will have enough leverage to prevent the legalization of movements they find objectionable,” Ismagambetov said.

As for 81-year-old Nazarbayev, his star keeps waning. More of his relatives and allies, many of whom grew obscenely wealthy under his watch, keep getting into trouble. The most high-profile victim of the purge so far has been his nephew, Kairat Satybaldy, who was thrown behind bars in March pending investigations on major embezzlement charges. Barely a week passes without somebody in his wider constellation either being arrested, losing their job, or becoming the subject of rumors they are about to be arrested or lose their job.

Until now, Nazarbayev himself has been off-limits, but even his position is looking weaker than ever. Under planned changes to the constitution, he is expected to lose the perks that came with his title of Elbasy, or Leader of the Nation, a sinecure bauble that granted him lifetime immunity from prosecution and ensured that his riches, of which he is said to have very many, would be protected.

Nazarbayev will continue to be honored as the “founder of the state,” so there is no suggestion he is also about to be slung into jail, but whatever authority he once wielded from behind the scenes will vanish almost entirely.

*Almaz Kumenov is an Almaty-based journalist.