From Shock And Awe To Stability And Flaws: Iraq’s Post-Invasion Journey – Analysis

By ECFR

By Hamzeh Hadad

Twenty years after the US-led invasion of Iraq, the country is now run by its eighth government, which took power in October 2022. Despite continuous fears of implosion, the political order and the elite in Iraq have proven resilient in the face of terrorism, civil war, threats of secession, and mass protests. Europeans should now acknowledge that the informal consociational system, the party politics, the patronage networks, and the competing paramilitaries are going to be long-term features of Iraqi governance.

This governance system was on ample display during incoming prime minister Mohammed al-Sudani’s first hundred days in office. He sought to please all sides in his consensus government (and arguably even those outside the government) through various crowd-pleasing measures. Instead of focusing on major reforms or challenging the status quo (something that his predecessor Mustafa al-Kadhimi tried and failed to do), Sudani’s government has prioritised infrastructure and services. Sudani is so intent on this priority that staffers in the parliament refer to his administration as “the services government”.[1]

Sudani’s approach should inform European efforts in Iraq. European governments should acknowledge the limitations of their influence on the turbulent political system in Iraq and plan for the possible when promoting internal reforms and democratic processes. They would not be setting any sort of precedent. European governments have diplomatic relations and shared interests with many other states, regionally and globally, that share some of Iraq’s long-standing challenges. Rather than seeking to make the Iraqi government into something it cannot be, European governments and the European Union need to identify priority areas where they can smartly nudge Iraq onto a positive trajectory.

Europeans no longer need to concentrate their efforts primarily on postwar reconstruction and the prevention of violent extremism. They should now concentrate on responding to the challenges that can make or break the Iraqi state over the coming decade, and are connected to European interests in stability, namely the economy and climate change. Iraq’s violence and extremism is closely tied to economic grievances, especially among the youth, so Europeans should also prioritise managing Iraq’s impending economic crisis. Climate change does not acknowledge borders and creates waves of migration and displacement. In Iraq’s case, this has already resulted in internal displacement from rural to urban areas, particularly in the south, but may also cause external migration in the coming years given the severity of the environmental threat in Iraq.

European governments are increasingly hesitant to engage with the Iraqi state on major economic investments outside of oil – to a large degree because of Iraq’s relations with Iran. As European-Iranian relations have taken a downturn in recent months, European governments increasingly worry that helping Iraq will in turn help Iran’s economy. But while Iraq shares a long border with Iran and the two countries are closely tied by culture, politics, and religion – the Iraqi state remains deeply nationalistic and has always attempted to carefully balance its relations with the United States and Iran. Being Iran’s neighbour should not condemn Iraq internationally. The more the US remains paralysed in its Iraq policy by Iranian-Iraqi relations, the more this will push Iraq closer to Iran. European governments should learn from the US experience and seek to achieve their strategic goals while reducing Iraq’s reliance on Iran, especially as Iraq is now growing closer to its other neighbours.

This policy brief will assess how the Iraqi state has consolidated political order through consensus building. It will consider how the Sudani government will try to work within these realities given the political baggage Sudani carries as the nominee of the Coordination Framework – a coalition of Shia parties, often viewed by the West as being backed by Iran. Even as he focuses on delivering basic services, Sudani will face many challenges. Among them is the lurking threat of the Sadrist Movement. The Sadrists won the most parliamentary seats in the 2021 election, but were nonetheless the sole major political party that did not take part in forming the latest government.

This policy brief also considers other domestic challenges that confront the new Iraqi administration, with a focus on its economic and climate challenges. It calls for Europeans to adopt a more pragmatic approach that is focused on helping Sudani to ease these two challenges in which Europe and Iraq have a shared interest. This approach may alienate some segments of the Iraqi public that are pushing for radical reforms, but many Iraqis are concerned with corruption and the economic situation and an increasing number of the largely youthful population are concerned by climate change.

Europeans should seize the opportunity to foster a stable and economically promising state in the region. A stable Iraq would not only reduce incentives for Iraqis to migrate, but also absorb regional migration pressures. Iraq has one of the largest markets in the region and is considered an untapped treasure by regional entrepreneurs. Investing in Iraq is no longer taboo for Gulf states. The opportunity that Iraq presents is both a cause and a consequence of the strengthening ties between Iraq and its Arab neighbours. Iraq has the potential to achieve an economy proportionate to its resources and assets. With economic strength and a respected role in the region, it can help establish a much -needed equilibrium in the Middle East.

The consolidation of the Iraqi order

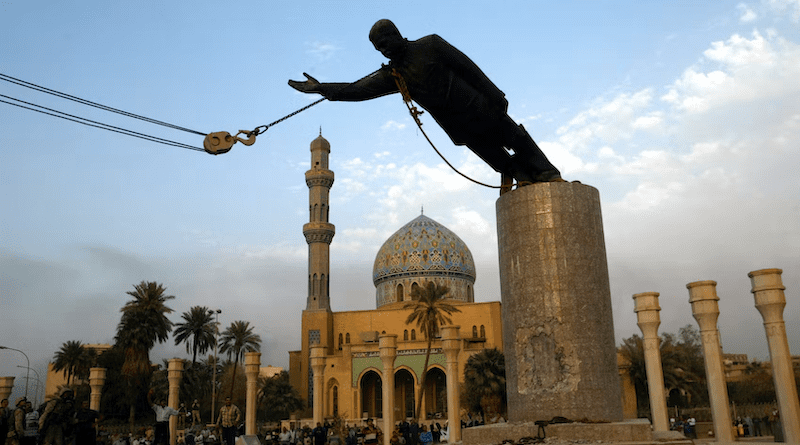

To understand Iraq’s position today, it is important to unpack the components of the political system established after 2003.

Iraq regularly holds competitive elections, despite obstacles such as occupation, civil wars, and terrorism. The electoral process has also evolved over the years from one nationwide electoral district to 18 governorate-level districts to 83 districts in 2021. Iraq has also experimented with both open and closed list proportional representation systems as well as transferable and non-transferable votes, and the Iraqi public has even opined in referendums on the equations for calculating seat shares from votes. Much of the controversy that surrounds Iraq’s election law has to do with whether it entrenches traditional parties or creates space for new political parties and independents.

Elections have often triggered a large turnover in parliamentarians and the prime minister has changed after every election except the one in 2010. Despite the competitiveness of Iraqi elections and the change in elected officials, Iraq has had only consensus governments since 2005 and has never transferred power to an opposition. Although election results determine how many ministries and leadership positions (and which leadership positions) in the state are allocated to a party, they do not restrict any major political party from joining the consensus government. Even if a party performs well, established political parties have already filled the Iraqi bureaucracy with partisan members and patronage networks through mass public sector hiring over the past two decades. Consensus has been the norm because no political party has been able to win the majority needed in an election to form a government. Parties need coalitions to form a government and they tend to invite everyone to join to prevent rivals from becoming spoilers.

The peaceful transfer of power between individuals across Iraq’s competing parties has become routine. But the process it takes to reach that agreement is less so, especially as many political parties in Iraq have the backing of armed groups. Even the parties that are not armed have nevertheless managed to protect themselves through alliances with the groups that are. The torturous process of getting to consensus was on full display in the latest government formation which, at over a year, was the longest in Iraq’s recent history. During government formation, tensions mounted when members of different armed political parties clashed in Baghdad’s International Zone in August 2022.

The violence resulted from a failed gamble by one political coalition – led by the Sadrist Movement – to create a government that would force their opponents, including parties affiliated with the heavily armed Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), into opposition. The violence started after the Sadrists were unsuccessful in assembling the numbers to vote in the majority government they wanted, despite winning the most seats (73) in the election. This failure frustrated Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, the leader of the Sadrist Movement, who forced all his MPs to resign and directed his supporters to besiege the Iraqi parliament. The Sadrists occupied the parliament for weeks without any violent incidents, though they clashed with state security forces and the PMF when the Sadrists tried to occupy other government institutions, such as the PMF headquarters and the Federal Supreme Court in the International Zone. The violence lasted only one night and resulted in tens of casualties (some estimate as high as 63) and ended with the military defeat of the Sadrists. The incident does show that Iraq continues to face stability issues, but the fact that a clash with an actor as significant as the Sadrists was resolved in one night and without devolving into civil war also shows how far Iraq has come. In Iraq’s post-2003 history, similar clashes had drawn on for weeks, if not months or years.

The next day, a dejected Sadr ordered his supporters to leave the International Zone and put down their arms. In doing so, he abandoned his goal of forming a majority government and allowed his rivals, the parties that constitute the Coordination Framework, to form a government without him. This move represented a lost opportunity for the parliament to have an opposition bloc. It also put the new government on high alert, knowing that the armed Sadrist Movement could again galvanise its supporters to take to the streets. This latent power is perhaps what has motivated Sudani to keep many Sadrists in their various government positions, including governors, deputy ministers, and director generals in key service sectors such as the health ministry. There have been exceptions, the highest profile being the removal of the governor of the Central Bank of Iraq, who was nominated by Sadrists in 2020. The decision to do so was based, at least in part, on the falling value of the dinar, rather than a partisan decision.

The events of last summer were a boost to the parties of the Coordination Framework. The leaders of the Coordination Framework succeeded in having Sadr marginalised and positioned their candidate to become prime minister. The Coordination Framework includes many political parties and individuals with strong relations with Iran, including Nouri al-Maliki’s State of Law Coalition and Hadi al-Ameri’s Fateh Alliance. The Coordination Framework also includes Shia parties with closer ties to the West such as former prime minister Haider al-Abadi and leader of the Hikma Movement, Ammar al-Hakim. The consensus government formed by the Coordination Framework also includes the major Sunni and Kurdish parties, making this government look similar to previous ones, just without the Sadrists in cabinet and parliament.

Colluding to preserve the status quo

Government through consensus has been the norm since the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. This model has often slowed political decision-making and at times allowed for incompetent individuals to take on important positions in the government because of their party affiliation. This system of consensus keeps armed actors happy, but it results in a poorly performing government, slow economic development, and erosion in critical government services. In turn, this poor performance frustrates everyday citizens and is exacerbated during lengthy government formations. This dynamic has also contributed to the relatively low turnout in the most recent elections. Iraqis flocked eagerly to vote in December 2005, after the constitution was ratified, with a participation rate of 79.6 per cent. This dropped to 43.5 per cent in the October 2021 election.

Despite this public frustration, there has been no successful attempt to overhaul the consensus system which is increasingly becoming entrenched as various political, ethnic, and religious factions seek to protect their stake in power. Consensus governments remain necessary in part because Iraq is still very politically fragmented. Since the invasion, no political party has ever won a majority in parliament (165 out of 329 seats). In addition, the constitution, which was adopted by a nationwide referendum in 2005, enforces a broad-based consensus in the selection of a president, requiring a two-thirds parliamentary majority (if this fails, as it frequently does, a run-off election takes place). The intent of this mechanism is to avoid a return to tyranny and ensure the buy-in of most of Iraq’s ethno-sectarian components in forming a government.

Another reason why this system has survived is because Iraq does not have a culture of parliamentary opposition. The established political parties refuse to be in opposition, regardless of how many seats they have won, as it means missing out on influence, positions, and access to state resources. As a result, activists and protesters adopted a popular discourse that rejects the consociational system in the 2019 October Protest Movement. This system was once considered necessary, by external powers and Iraqi anti-Saddam opposition figures, for preventing a diverse country from falling into violence. Iraqi political parties largely rejected the calls for systematic reforms in 2019, and instead chose to collude in protecting a system that was originally designed to prevent them from fighting one another.

Sudani’s priorities

The new Sudani government – despite the lengthy and at times bumpy government formation process – represents continuity rather than rupture. Overall, the Sudani government began its term in a better position than most governments before it. Sudani does not have to deal with a third of Iraq’s territory under Islamic State group (ISIS) occupation, as Abadi did in 2014, or taking office as the nation is engulfed in a pandemic and increasing Iran-US tensions, as Kadhimi had to in 2020. The government has yet to pass a federal budget for 2023, but, when it does so, it will not have to account for paying reparations to Kuwait as Iraq has now fully paid that off. In addition, Iraq’s foreign reserves are at a record level due to high oil prices and limited spending by the previous government, a caretaker government that could not pass a federal budget in 2022.

Sudani has so far balanced the fragile political alliances both within and outside parliament and attempted to ensure his own survival by steering away from pushing for major reforms, especially in the security apparatus. No cuts are planned for the PMF in the budget, and Sudani is continuing to deal with them as an official military institution of the state like the Counter Terrorism Service or the Kurdish Peshmerga Forces.

Sudani has sought to empower himself within the Coordination Framework by seeking Western backing. As many within the Coordination Framework have strong relations with Iran, Sudani has sought Western support to distinguish himself and provide a different asset to his coalition, which does not want Iraq to become a pariah state again. Sudani is not the first prime minister to seek and receive Western backing. Abadi and Kadhimi both did so as well and Western support empowered them and allowed them to push for a more balanced foreign policy agenda. Sudani is trying to repeat this tactic, and accordingly has provided avenues for Western countries to work with Iraq.

For now, Sudani seems well positioned to drive forward his priority to deliver services across Iraq and lead the country out of two decades of continual violence and emergencies. Sudani’s position is further bolstered at a moment when both Iran and the US have demonstrated a mutual interest in avoiding any destabilisation of Iraq and when Iraq’s neighbours have opened a pathway for regional de-escalation. This moment opens new possibilities for European actors to engage with Baghdad to cooperate with the Iraqi government and Iraqi civil society in areas where Sudani can deliver.

Iraq’s challenges

Iraq may have found some internal equilibrium, but significant dysfunctions tied the hands of several of Sudani’s predecessors and will continue to limit his capacity to effect change. From the problem of deeply rooted corruption, to armed insurgents, to the economy and terrorism, successive governments have been hard pressed to deliver breakthrough results. As Sudani grapples with these challenges, there are three key sectors where European involvement can assist his government in stabilising Iraq. They are shoring up the economy, implementing a policy for tackling climate-related challenges, and bolstering Iraqi security. European ambitions for improvements in these three areas need to be modest and should focus on where Iraqis and Europeans share interests and where European support can have the most positive impact.

Corruption and economic challenges

Iraq is relatively wealthy among recipients of foreign aid. It is, as European donors often note, an “Upper Middle Income Country”, but a host of problems plagues Iraq’s economy. The roots of these problems lie in widespread corruption, the youth bulge, and vulnerability to fluctuations in global oil prices due to an undiversified economy.

Corruption is one of Iraq’s greatest challenges – it is ranked 157th out of 180 countries in the Transparency International Corruption Perception Index for 2022. It is not a new problem. Corruption plagued Iraq long before 2003 in part because the country faced strict sanctions after the first Gulf war and access to state services became accessible only through bribes and connections. That legacy continued through the violence after 2003 and remains today. Fighting corruption has been on the agenda of every government since, but there has been a struggle over where to begin. There is both high-level corruption that diverts vast resources as well as low-level corruption that citizens experience every day. High-level corruption is difficult to address because the political parties involved will use any tool, including the armed groups at their disposal, to protect their interests. There are, however, opportunities to tackle low-level corruption, especially by reducing the country’s dependence on cash.

One of the underlying economic challenges facing Iraq is rapid population growth and a young population at a time when the government is struggling with job creation. In 2003, Iraq’s population was about 27 million, but it is estimated today to be over 40 million. According to UN data, Iraq’s population is projected to grow by two per cent annually, meaning that by 2032 its population will be over 50 million. Currently, about 60 per cent of Iraqis are under 25 years old. Iraq’s youthfulness is not an outlier: youth bulges, the demographic trend in which the proportion of young people is greater than that of older people, are a regional phenomenon.

A youthful population can be an opportunity or a curse, depending on the economic and social policies that are put in place. On the one hand, youth bulges are correlated with violence, specifically with civil conflict, particularly when accompanied by high levels of unemployment. On the other hand, youth constitute valuable human capital. Iraq’s challenge is to manage the youth bulge strategically, but it has not yet been able to do so, given its previous preoccupation with existential security threats.

Another major issue for the Iraqi state is its dependence on oil and its lack of economic diversity. The latest Iraqi budget draft reveals that 87 per cent of Iraqi state revenues comes from oil sales.[2] This dependence has made Iraq vulnerable to oil price shocks. Most recently, the Iraqi economy plummeted in 2020 when global oil prices fell because of the covid-19 pandemic. The state struggled to meet the public sector payroll, let alone inject any significant stimulus package into the economy. The Iraqi government quickly turned to international organisations such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, as well as to Western missions, for grants and loans to get through the financial crisis.

Simultaneously, in 2020 the government produced an economic white paper, which was meant to be a blueprint to reform the Iraqi economy to both get through the pandemic economic crisis and to diversify the Iraqi economy for the long term. Even in the most ideal scenario, the writers of the white paper were aware that implementing the reforms would be difficult.[3] So much so that, when global oil prices bounced back the next year, the white paper was ignored by the same government that wrote and adopted it.

By the time Sudani was elected prime minister in October 2022, Iraq’s central bank reserves were at an all-time high and the government no longer felt pressed to pursue politically difficult reforms. But the Iraqi public sector remains a growing burden, with no major revenue stream other than oil exports and a private sector not large enough to lessen the burden on the state for employment. The economic reforms in the white paper are still necessary to manage an ever-expanding and youthful population that requires adequate healthcare, services, education, and employment.

Unfortunately, the Iraqi government sees no incentive for reforms when global oil prices are high. Worse, as long as monthly oil revenues remain bountiful, there are growing demands from citizens for more public sector hiring. An important lesson for Europeans therefore is that they have greater influence with Baghdad when oil prices are low and should utilise future such openings to push the government for more dramatic reforms. During times of abundance, Europeans should focus on more modest reforms, though as part of a broader vision.

As oil prices are now high, Europeans need to be aware that Sudani and his ministers will seek assistance and advice (as they did during a recent tour of European capitals and Washington) but will not necessarily tie these to critical economic reforms. With provincial elections around the corner and all eyes on the next parliamentary election, no official will push for reducing the public payroll or stop growing their patronage networks. The proposed 2023 federal budget is the highest in Iraq’s history at 199 trillion Iraqi dinars (roughly $153 billion). The size of the current budget and the economic outlook point to more modest involvement from Europe. European governments are simply not going to be able to put forward enough development aid to influence the Iraqi government when oil prices are high and the government budget is so large.

Accordingly, European efforts should focus on issues that align with the direction of the Iraqi government, such as furthering investment, improving government efficiency, and strengthening ties with regional partners. Despite the large budget, Iraq has a poor record on budget execution and often failed to spend what its budget promised it would. In the period of its last budget (2021), the Iraqi government only managed to spend 79 per cent of allocated funds.

Climate change

Iraq faces significant environmental challenges including water scarcity, pollution, and rising temperatures. The country is already experiencing climate change and its citizens are becoming increasingly attuned to the natural crisis that has long been ignored by successive governments.

Historically, Iraq has relied on its rivers. Nearly every major Iraqi city has been built along the banks of rivers. They have been a source of livelihood for agricultural and fishing communities throughout the country but, in the last few years, water levels have become visibly lower and entirely dry in some areas. This scarcity has upended entire agricultural communities and put pressure on urban centres. Issues of water scarcity are attributable both to climate change and to governance failures in water diplomacy and planning. Iraq has failed to attain adequate volumes of water from upstream neighbours, which complain about Iraq’s outdated infrastructure and primitive irrigation practices. The rapidly rising temperatures and sandstorms also exacerbate water scarcity and threaten to make southern cities, especially Basra, uninhabitable.

Climate change has already caused internal displacement of the Iraqi population and may result in transforming an internal displacement crisis into a refugee crisis. The drying up of the rivers and lakes, the salination of water in the south, and the frequent sandstorms are driving new waves of internal displacement. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) has a tracking matrix that has traditionally been used to follow internal displacement from terrorism (the ISIS war), but more recently the IOM has begun paying attention to climate-caused displacement. According to data collected up to March 2023, over 70,000 individuals remain forced to move due to water scarcity and other environmental issues from ten of Iraq’s 18 governorates. In the near future, climate migration will put even more pressure on densely populated urban centres in southern Iraq such as Najaf and Karbala

Unfortunately, Iraqi officials usually approach climate change on a year-to-year basis and procrastinate on preventive action to, for example, avert future water scarcity during periods of ample rainfall. But at this point, the visible signs of climate change and their impact on the daily lives of ordinary Iraqis in recent years has forced the Iraqi state to acknowledge the vast problems that lie ahead. This admission has not only inspired the Mesopotamia Revitalisation Project but also more long-lived endeavours such as the resurrection of the Ministry of Environment in 2022 and the establishment of a climate change envoy in the Prime Minister’s Office. It is critical that the Iraqi government’s efforts to address climate change are associated with an institution, rather than with an individual.

Many of Iraq’s environmental challenges are legacy issues and can be traced back several decades to policies of previous governments and occupying powers. But the environmental challenges that Iraq confronts were also to a great extent caused by the irresponsible practices of developed nations. Like many developing nations, Iraq will pay a large and unfair price for climate change.

Climate change knows no borders, but climate vulnerability does. As a recent article in the New York Times showed, different cities (in this case, Basra and Kuwait City) have different abilities to respond and acclimate to the same environmental challenges depending on their wealth, stability, and levels of development. Iraq, for example, ranks 99th out of 182 countries in terms of climate vulnerability. Meanwhile, its bordering neighbours, except for Syria (116th), are all less vulnerable. (Jordan is 49th, Turkey is 28th, Iran is 57th, Saudi Arabia is 74th, and Kuwait is 53rd.) By contrast, Yemen is among the most vulnerable in the world at 160th, while neighbouring Oman is 81st out of 182.

Many of the world’s poorest countries are vulnerable to a crisis that was largely created by industrial countries and by the unsustainable living standards of the wealthiest nations. The countries in the EU have contributed 22 per cent of the global cumulative emissions since 1751, while Iraq has only contributed 0.25 per cent. Considering Europe’s historical impact on the climate and its current involvement in gas flaring in Iraqi oil fields through companies such as BP and Eni, tackling climate problems in Iraq is a matter of moral responsibility.

Managing security deficits

Iraq’s continuing security deficits will likely plague the country for some time to come. One key factor that drew European political, economic, and security attention back to Iraq after the 2003 invasion was the growth of ISIS in Iraq. Through their direct support to Iraq, as well as to the US-led anti-ISIS coalition since 2014, European governments and the EU have taken part in many anti-terrorism projects in Iraq. But since Abadi announced the territorial defeat of ISIS while he was prime minister in December 2017, European attention has dwindled. Nevertheless, remnants of the terrorist group have resorted to small-scale attacks, taking advantage of the security vacuum between federally controlled Iraq and Iraqi Kurdistan.

This security vacuum persists in areas where citizens had to flee early in the ISIS war and the threat of attack still makes it difficult for them to return, even six years after the war ended. As of the start of 2023, over 1 million Iraqis are still displaced and the largest increase in displacement occurred in disputed territories, including instances of secondary displacement due to recurrence of violence, according to the IOM.

The places that have seen further displacement are Sinjar district (Ninawa governorate), Al-Ba’aj district (Ninawa governorate), and Khanaqin (Diyala governorate). These areas all lack security and provide space for armed groups, including the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), to operate and make durable returns difficult.

In many adjacent areas that also suffered under ISIS occupation, reconstruction programmes are under way. However, despite significant international investment in reconstruction and rehabilitation, the main obstacles to durable returns are the lack of economic opportunities. International organisations have tended to focus on reconstruction, social cohesion, and economic revitalisation as a three-pronged approach. But the structural barriers of the Iraqi statist economy, particularly stringent business regulations and primitive banking structures, have limited the success of their efforts.

An ISIS comeback in these locations remains unlikely, but their diverse make-up and their demographic shifts may create more ethno-sectarian violence in the future. In some parts of the Ninawa plain, for example, Assyrian and Yazidi communities are wary of the migration of Shabaks, particularly in Bashiqa and Bartella. There have also been historical Arab-Kurdish demographic tensions in the areas of Kirkuk and Diyala. The main fear of ISIS resurgence has to do with the rehabilitation programmes of the Al-Hol and Al-Jada’a camps, which are being overseen by the government of Iraq in collaboration with various UN agencies. Al-Hol in particular is frequently described by Iraqi and foreign officials, including the Iraqi national security adviser, as a ticking time bomb, due to the presence of ISIS affiliates in the camp alongside unrepatriated victims and youth who are vulnerable to radicalisation.

The threat of terrorism has faded in the last few years, but it lurks in the background. Terrorists are emboldened by gaps in Iraq’s security apparatus that result from the multiple security organisations operating in Iraq. These security organisations have various ties to the central state structure and sometimes have conflicting agendas and goals. This includes both traditional and non-traditional security organisations such as the Iraqi army and police on the one hand, and the PMF and the Kurdish Peshmerga on the other.

Their lack of unity creates an enduring challenge for the Iraqi state. Strategic planning is necessary to curb both the immediate and the structural causes of terrorism and violence. To see the effects of a lack of planning, one need only notice what happened when tensions arose between the Kurdish Peshmerga (the KDP faction) and the rest of the Iraqi security forces after a referendum on Kurdish independence was held in disputed territories in September 2017. In response, Iraqi security forces (including the PMF) extended their control over most of the disputed territories that had been held by the Peshmerga since the war against ISIS. This military movement was a delicate operation that could have created a new civil war.

Another source of instability in Iraq are the foreign incursions taking place regularly in Iraqi Kurdistan, a region once considered the safest in Iraq. Turkey has launched air strikes into Iraqi Kurdistan, targeting the PKK, an EU-listed terrorist group that Turkey believes Iraq cannot or will not suppress. Numerous such strikes have resulted in civilian casualties. Indeed, Turkish air strikes killed at least 98 civilians between August 2015 and December 2021. Iraqis are dismayed by Turkey’s ability to infringe on sovereign territory with seemingly no consequence.

On its eastern border, Iran has also made life tough for Iraqis. In March 2022, a dozen Iranian ballistic missiles targeted the home of Baz Karim, the CEO of KAR Group, the largest Iraqi private sector energy company, in Erbil. Iran claimed this location was being used as an Israeli training facility. Iran has also targeted Iranian-Kurdish opposition groups operating in Iraq. These attacks are disruptive to local communities and threaten to turn Iraq into a theatre of regional and global score settling.

What Europeans should do

European leaders and policymakers need to acknowledge that addressing Iraq’s multitude of challenges will likely be a long-term process. There are areas that Europeans will be unable to impact – most notably, major security sector or political reforms in Iraq. But there are also ways to support Iraq in maintaining a degree of stability and improving the livelihood of ordinary Iraqis.

This paper has outlined some areas of challenge in the economy, environment, and security where Europe could make a difference, and that, if left unaddressed, could spiral into larger problems that might affect European security. The Iraqi political elite have shown that they can survive crises, but improving governance is a proactive measure that can both prevent domestic instability as well as reduce the structural causes of migration (chiefly poverty and unemployment).

In planning for their engagement with the Sudani government, European governments and the EU should prioritise the following areas.

Support Iraq’s economy to go digital

Iraq’s economy faces huge challenges. It is unlikely that Sudani can implement major reforms of the economy. But there are concrete areas where European stakeholders can positively contribute by working with both the public and private sector in Iraq.

For example, Europeans should help reduce corruption by supporting Iraq to digitise its economy. As one of the last cash-based economies in the world, the use of cash creates enormous opportunity for petty corruption to take place. Because of the sanctions in the 1990s, Iraq lagged technologically, which considerably hindered its banking sector. The lack of a developed banking sector means many Iraqis are forced to use cash in both small transactions and large ones, such as purchasing cars and homes.

Iraq now has the technological infrastructure to move beyond cash; it just needs the incentive. For example, many of Iraq’s public sector workers have bank accounts and receive their salary and pension through direct deposit, but they withdraw that cash, and choose not to use digital payments and banking.

Digitising Iraq and easing its dependence on cash will be one of the leading factors in addressing corruption in Iraq. Utilising digital payments for passports, government identification, taxes, utility bills, and fines will limit the space for petty corruption that citizens witness directly and improve the experience at public-facing government offices.

And digitisation can also reduce high-level corruption by providing a clearer trail for the movement of state funds. It will also help with generating non-oil revenue. State revenue will be traceable through digitisation and different ministries (other than the Ministry of Oil) can bring in revenue. Implementing digital payments, for example, will not only improve the ability of the Ministry of Electricity to collect payment for energy use, it will also decrease demand on the national grid as Iraqi households will be more accountable for their consumption.

In the past, poor infrastructure kept Iraq reliant on cash, but that is no longer the case. With 4G mobile data, higher internet speeds, and fewer electricity cuts, Iraq’s transition to a cashless economy now requires only political will and expertise. Europeans are the pioneers in transitioning away from cash-based economies: Norway, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands are all nearly cashless.

Helping Iraq digitise will help combat corruption, improve services, and create non-oil revenue. Sudani has set up a committee tasked with implementing digital payments across the public and private sectors and has called for foreign expertise to help, as well as encouraged citizens to adopt digital practices. This need for foreign expertise presents an opportunity for European companies to invest in Iraq’s financial sector by partnering with Iraqi financial institutions. Together, they can push electronic payments using both European experience in transitioning away from cash and the latest technology.

European governments and the EU should also support Iraq to expand private sector jobs. Iraq will need job creation in both the private and public sector to meet the youth bulge challenge. The Iraqi government has expanded the public sector significantly since the invasion. In 2003, the Iraqi state employed an estimated 1,200,000 public sector employees. By the end of 2020, it had reached 4,500,000 public sector employees and 2,500,000 pensioners. The Sudani administration has continued public sector hiring since then.

Experts agree that Iraq’s public sector is both bloated and inefficient, but the private sector cannot immediately serve as a replacement without the proper incentives. Iraqis prefer public sector employment for its reliability and benefits, including generous pensions, loans, grants, and even property. The private sector, by contrast, may pay higher wages, but it is not well regulated and private sector employees do not feel protected from potential employer predation, including unstable wages, workplace harassment, and lack of contributions to retirement funds.

In order to nurture a private sector, there needs to be a concerted effort to change the incentive structure, which will require more social security spending rather than more public employment. Currently, Iraq’s public employment is akin to social security spending, given how unproductive many public sectors jobs are. If the same funds were reimagined as welfare funds, it would create enough of a social safety net for more individuals to seek private sector employment opportunities.

These funds can also be used to create incentives for private sector jobs by increasing the government’s contribution to the private sector retirement fund. In addition, creating a credit system in Iraq would allow individuals to seek out loans without needing a government backer, and thus reduce the preference for public sector employment.

Europe’s support is vital in this arena because, unlike the US, European countries have managed to create strong social safety networks for their citizens, while preserving their open-market economies. Eastern European countries, such as Poland and Romania, are particularly well suited to provide advice and expertise to Iraq, given their own transitionaway from a statist economy in the 1990s. Many eastern European countries were able to privatise state-owned enterprises and to build private sectors.

Europe can also support Iraq’s economy by seizing opportunities for constructive and profitable investment. Europeans have long encouraged the Iraqi government to grow the private sector, but it has been difficult to persuade European companies to invest in this area given the levels of corruption, insecurity, and red tape in Iraq. There are some thriving Western companies operating in Iraq, such as the Spanish-owned retailer Mango and American food chains like Burger King and Cold Stone Creamery, as well as corporations such as the Uber-owned Careem.

The Iraqi government can address the challenges facing foreign investors by focusing on the demonstrably successful sectors – like retail and food – as well as by partnering with other international investors, including investors from Gulf Arab states that have more experience with businesses in Iraq. For example, American franchises such as Pizza Hut and Kentucky Fried Chicken, which opened in Iraq in early 2023, are owned by the Kuwait-based Americana Group. Given the recent regional opening by Gulf Arab states to Iraq, there is likely to be increasing private and public sector investment in Iraq by its Arab neighbours.

Help Iraq address climate challenges

Europe can support Iraq in addressing climate change by providing targeted resources and expertise. Many Iraqi political leaders have of late begun to acknowledge the need to address climate change, and some, including the new prime minister, are leading the process. Iraq is a latecomer to the issue, having only adhered to the UN climate convention in 2009 (almost two decades after most of its neighbours) and so has not been able develop a deep understanding of the subject. For example, key line ministries that are crucial to the problem are still not as involved as their counterparts in Saudi Arabia or the United Arab Emirates are. These negligent ministries include the Ministry of Oil, which is responsible for gas flaring and the mitigation of methane emissions, and the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of Water Resources, and the Ministry of Housing and Construction, which are responsible for climate adaptation.

According to Iraq’s climate change envoy, Fareed Yasseen, the country needs expertise from Europe to adapt to climate change.[4] One way to leverage Europe’s support is to identify worthwhile pilot projects that are being developed in Iraq by, for example, the Ministry of Agriculture, and sharing expertise to help better implement and scale up these projects.[5]

Expertise can come in the form of providing advisers to the relevant Iraqi institutions and creating a Climate Contact Group. This contact group would consist of diplomatic missions focused on climate change, much like the Iraq Economic Contact Group. One area, for example, where capacity is lacking is in how to measure climate data. Iraq lacks the means to measure its greenhouse gas emissions, especially methane. This data will be necessary to participate in the carbon markets, but this is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of missing data.

There is already an interest among public servants in various ministries to address climate change. Representatives of various ministries, including the Ministry of Electricity, the Ministry of Environment, and the Ministry of Planning, as well as the central bank, have put together a cross-government initiative – the National Initiative for Energy Support and Emission Reduction. That initiative would be an ideal partner for European development organisations or the proposed Climate Contact Group to work with.[6]

By demonstrating the need for multi-actor cooperation in climate change through the proposed Climate Contact Group, Europeans can lead by example and encourage the Iraqi government to create more departments and organisations that have a mandate to be partners on climate change. One example would be to create a climate or environment department in each ministry, like the department of women’s empowerment, which was created in the past. Climate experts working on Iraq have complained about the lack of coordination among relevant ministries.

The need for data leads to the second area in which Europeans can assist Iraqi climate efforts: supporting Iraq in regional dialogues regarding climate change. The Iraqi government not only needs help obtaining national data, but also acquiring data with regards to its upstream neighbours, Iran and Turkey, to deal with water scarcity. Iraq has struggled to conclude negotiations with Iran and Turkey over the amount of water those countries release into rivers that flow into Iraq. According to a senior Iraqi official, neither country is interested in sharing its data on water usage with Iraq.[7] With European support using satellite technology, Iraq could measure how much water is lost in Turkish and Iranian dams from evaporation (water that could be released to Iraq rather than wasted).

With the recent thaw in Iran-Saudi relations, Iraq is likely to grow closer to its neighbours, particularly those in the Gulf Cooperation Council, which have now joined Iraq in having ties with Iran. New regional convenings or regional Conferences of the Parties (COPs) could initiate concrete negotiations and action plans to tackle common climate challenges facing the region. The regional COPs are a great opportunity to encourage awareness and dialogue within Iraq. As my ECFR colleague Cinzia Bianco has recommended, European governments should also support the creation of a regional platform to address climate change issues, beginning with a focus on Iraq’s water scarcity.

Europeans should also support the growing number of civil society organisations, climate activists, and youth volunteer groups that are promoting environmental literacy. Iraq’s civil society organisations are ideal partners in climate change. There are ample opportunities to bring them closer to their regional peers for learning and for cooperation, a process that Europeans can help facilitate and support. The Iraqi public’s interest in climate issues ebbs and flows with the water levels of the rivers and with the number of sandstorms. Civil society organisations try to counter this peripatetic attention and play a key role in informing society about the structural causes of climate change and how to counteract them. For example, they can correct misinformation about Turkey’s dams being the sole cause of water shortages. However, the organisations face a challenge in that, although they can find youth volunteers, they struggle to attract local funding and need international support. The EU should provide specific grants for climate-related civil society programmes in Iraq.

There are also smaller actions European embassies in Iraq can take regarding climate change. Various international organisations with European backing have held conferences and workshops with Iraqi youth and civil society on the importance of addressing climate change, but they have suggested band-aid solutions such as recycling or consuming less plastic without acknowledging the lack of recycling infrastructure or the larger forces at play. At the same time, Western diplomats regularly use gas-guzzling convoys, keep cars turned on for security reasons (thereby emitting pollution), and do not practise what they preach in their own embassies. At the United Nations compound in Baghdad, for example, there are recycling bins that everyone knows empty into a regular trash collection vehicle. As Iraqi youth grow more connected to the world, these attitudes are alienating and patronising. Europeans can use their presence in Iraq to instead lead by example, focusing on a sustainable presence and on promoting a message that acknowledges Iraq’s position as a victim of climate change.

Bolster Iraqi security

Europeans should steer clear of controversial and highly sensitive security topics, such as the role of the PMF and its relationship with the state. This is an area where former prime minister Kadhimi was unable to secure progress despite making it a flagship goal. Kadhimi encountered pushback early in his premiership from political parties and armed tribes when going after specific individuals affiliated with or sympathetic to the PMF. Those groups were simply too powerful for an unaffiliated prime minister to resist. Given that there is a well-documented link between joining armed groups and economic vulnerability, Europeans should instead adopt an indirect approach to tackling this issue and channel their concerns towards economic development.

More directly, European countries and the EU can bolster Iraqi security by focusing on three key areas. Firstly, Europeans should take advantage of the regional opening between Saudi Arabia and Iran to promote greater regional integration and security. Iraq has frequently been caught in the crossfire of regional and international tensions involving Iran, Saudi Arabia, Israel, and the US. Despite this (or perhaps because of it), Iraq has had an enduring interest in playing the role of regional mediator as well as strengthening its ties with its neighbours. Iraqi leaders know that Iraq’s stability is dependent on regional peace. For their part, Europeans can encourage regional integration and provide a model for regional cooperation initiatives. The EU is the world’s most successful example of regional integration and thus is uniquely positioned to provide leadership and advice to the Middle East on regional cooperation. My ECFR colleagues Julien Barnes-Dacey and Cinzia Bianco have provided an example of how Europeans can capitalise on the Iran-Saudi rapprochement to promote peace in Yemen.

Secondly, Europeans can help cool tensions and press for greater cooperation between the Kurdish regional government in Erbil and the federal government in Baghdad, particularly on continued anti-ISIS efforts. The Iraqi security forces and the Peshmerga coordinated throughout the war to defeat ISIS, with the support of the Global Anti-ISIS Coalition. This coordination should continue especially as remnants of ISIS linger and prey on vulnerable communities in disputed territories. If this issue goes unaddressed, the grievances of the local population could grow into a national dispute.

Europeans are experts on security coordination in part because of their experience with the vast border of the EU, which stretches across many states and security organisations. They are ideally placed to advise on addressing security vacuums between the various security forces in Baghdad-controlled Iraq and Iraqi Kurdistan. The gaps in security arising from a lack of Baghdad-Erbil coordination are an important cause of outward migration from Iraq, largely to Europe.

The Sudani administration has begun addressing these security risks by including Peshmerga leadership in National Security Council meetings alongside all other Iraqi security forces, something previous Iraqi leaders failed to do. Europeans should build on this new trust and encourage greater cooperation by providing military support to both sides conditional on continued cooperation.

If the Iraqi security forces and Peshmerga can operate joint brigades and command centres to fill the current security vacuum and extinguish the remaining ISIS threat, then Iraqi policymakers can direct their efforts towards further professionalising the PMF and Peshmerga. Europeans may be tempted to turn their attention to disbanding the various paramilitary groups that they consider too friendly to Iran – or unifying the two Kurdish Peshmerga forces. But such efforts risk backfiring. This cannot be done if the main threat that these paramilitaries exist to repel – ISIS – remains, even if on the periphery. Moreover, the lesson of 2003 should linger in the minds of external actors: dissolving an Iraqi security institution without a clear strategy is ill advised and likely to invite violence.

Iraq’s normal problems

Twenty years after the US-led invasion of Iraq, the country’s political system is maintained by a mix of constitutional, legal, and informal practices. Despite the constant prediction that the Iraqi state would soon collapse, it has demonstrated resilience in the face of many crises. But it continues to operate in an unstable environment. The formation of Iraq’s latest government under the leadership of Sudani, and the recent thaw among Iraq’s neighbours, creates an opening for European countries to work with Baghdad. They should seek to usher in incremental yet important changes in concrete areas where there is both a European interest and a capacity to influence Iraq.

Iraq has now transitioned from having exceptional crises and challenges to ones that are shared by many other countries, particularly in the economic and environmental sectors. This includes over-reliance on oil, a weak private sector, and climate vulnerability. There are many avenues for cooperation with Europe to deal with these problems.

Security is another area of potential Iraqi-European cooperation. Security has improved generally in Iraq, but some specific areas in the disputed territories remain vulnerable to terrorist attacks and Iraqi Kurdistan faces ever more foreign incursions. Here, European experience in collective security structures as well as their diplomatic weight in Iraq are valuable assets in improving security coordination in the country.

Iraq’s political system may be durable, but the country faces a host of problems. But just as Iraq has problems, it also has powerful tools to address these challenges, including democratic institutions (e.g. elections), a robust civil society, a battle-hardened security force trained by the international coalition, abundant natural wealth, an important geostrategic position, and significant human capital. Rather than seeking to tackle overwhelming and multi-layered challenges that cannot be solved, Europeans need to have a more precise picture of where Iraq stands and choose the strategic areas in which they can help Iraq.

About the authorL Hamzeh Hadad is a visiting fellow with the Middle East and North Africa programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations. In 2021, Hadad was an adviser to the president of the Trade Bank of Iraq.

Acknowledgments

I am thankful to my colleagues at the European Council on Foreign Relations, Julien Barnes-Dacey, Ellie Geranmayeh, and Jeremy Shapiro for their advice, feedback, and editing during research and writing and to Nastassia Zenovich for providing graphics support. In Iraq, I especially want to thank His Excellency, Ambassador Fareed Yasseen, for his time and valuable expertise on climate change as well as the many other Iraqi officials and experts for their input.

Source: This paper was published by ECFR and made possible by support for ECFR’s Middle East and North Africa programme from Fondazione Compagnia di San Paolo.

[1] Author’s conversations with parliament staffers in Baghdad, Iraq, 26 March 2023.

[2] Budget draft provided to author by Iraqi official, Baghdad, March 2023.

[3] Author’s conversation with one of the contributing writers of the white paper in Baghdad, Iraq, 30 March 2023.

[4] Author’s interview with climate change envoy of the Republic of Iraq, in Baghdad, Iraq, 29 April 2023.

[5] Author’s interview with climate change envoy of the Republic of Iraq, in Baghdad, Iraq, 29 April 2023.

[6] Author’s conversation with representative of the initiative in Baghdad, Iraq, 4 April 2023.

[7] Author’s interview with climate change envoy of the Republic of Iraq, in Baghdad, Iraq, 29 April 2023.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.