The ‘Goebbels Method’: RIA Novosti As Window Into Russian Propaganda – Analysis

By Manucharian Grigoriy

Some of the Russian state-owned media are known globally, like RT or Sputnik, which continue to resonate across the West with their far-right pro-war pro-Putin propaganda. But some such news agencies don’t cross the domestic borders and instead focus on Russian-speaking consumers. RIA Novosti is one of them, with its headquarters located in Moscow.

In December 2013, not long after Putin’s controversial reelection, the RIA media group was dismantled. It was later replaced with the Russia Today brand (Россия Сегодня) which absorbed RIA’s assets, some of its employees, and also appropriated its name for a new media resource.

RIA Novosti is now known as the Russian regime’s ally. On February 26th, at 8 AM Moscow time, it published a pre-written article to mark the end of the special operation in Ukraine. But due to Russian defeats in key areas on the Eastern borders, the article was deleted from the official website. Nevertheless, it is still available thanks to the WBM online archives.

Entitled “The advent of Russia and a new world” (Наступление России и нового мира), it declares that “Russia is restoring its historical fullness, gathering the Russian world — the Russian people — together, in their entirety, from Great Russians to Belarusians and Little Russians.” It continues by stating that “if we had abandoned this, if we had allowed the temporary division to take hold for centuries, then we would not only betray the memory of our ancestors but would also be cursed by our descendants for allowing the disintegration of the Russian land.” This imperial message is then completed with the following: “Vladimir Putin has assumed, without a drop of exaggeration, a historic responsibility by deciding not to leave the solution of the Ukrainian question to future generations.”

This article, published in error, demonstrates that Russia was planning to conquer Kyiv in two days, more or less. Yet, after more than a hundred days of the war, thousands of dead, and unprecedented global geopolitical consequences, Ukraine still stands. And so too does the Russian propaganda.

On April 3rd, after Russian war crimes in Bucha started to unravel, covered extensively by Bellingcat, RIA published another now-controversial article. Entitled “What should Russia do with Ukraine?”, the article argues for ethnocide and ideological purges. The term “de-Ukrainization” is used extensively in relation to mass repressions of the inhabitants of Ukraine who, as “passive Nazis […] are also guilty.” The term “denazification” — one of the Russian casus bellorum along with Ukraine’s demilitarization — was employed there 38 times. The main argument is that “denazification will inevitably become de-Ukrainization,” but also the “unavoidable de-Europization” of Ukraine.

RIA Novosti’s standpoint throughout only these two articles confirms that this war is not a war between Russians and Ukrainians, as some Russians are fighting for the Armed Forces of Ukraine, and some Ukrainians are fighting in the Russian Armed Forces. This is not a war of religions either — both are mostly orthodox.

This is hybrid information warfare to dominate spheres of influence and to sell a narrative. In 2014, in Crimea, Russia propagated then successively sold the story of Crimeans cheering the Russian “green men” and happily voting at the referendum for adherence to Russia.

And it worked: the Minsk agreements were not respected but rather redacted, again and again; the MH17 flight criminal prosecution led nowhere; and, at the same time, between 2015-2022, France along with Germany armed Russia with some €273 million of military hardware, including bombs, rockets, and missiles – all of which is likely being used against Ukraine now.

Russian propaganda certainly came in handy for the Kremlin over the past decade. Yet one of the major differences between then and now is the general awareness of its methods.

Portraying the Nazi Phenomenon

RIA Novosti associates tags to each of its articles. One of them is “Nazification,” created in late March. To this date, it applies to 22 articles.

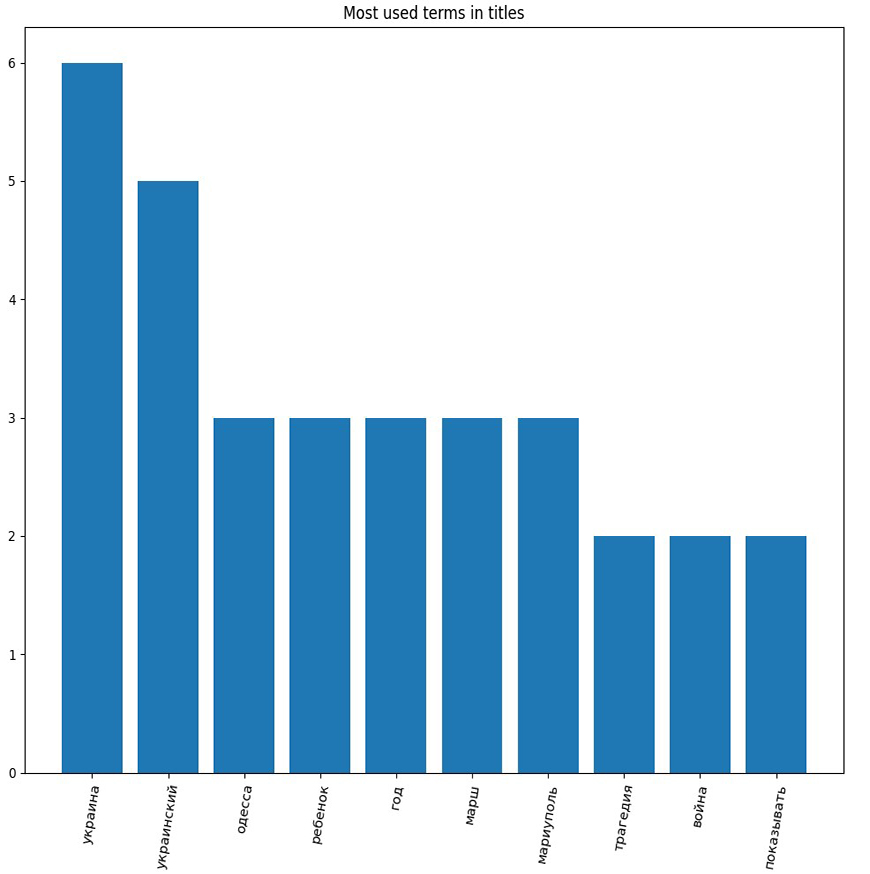

By automatically extracting and analyzing the most used terms across their titles, the top-10 is as follows:

In the titles, “Ukraine” (ru. Украина) is predominant (used 6 times), “kid” (ru. ребёнок) and “Mariupol” (ru. Мариуполь) are also worth noting (used 3 times), as well as” tragedy” (ru. трагедия) and “war” (ru. война) (used 2 times).

Such terms in article titles put into focus the violent events unfolding in Ukraine. It then shifts to the younger generation of its victims, and to the place where most tragic events happened: Mariupol.

It is not the first time that Russian propaganda has disseminated this narrative. The crucified boy story, which came to light in July 2014, did the same by putting a child in a violent narrative and attributing it to Ukrainians.

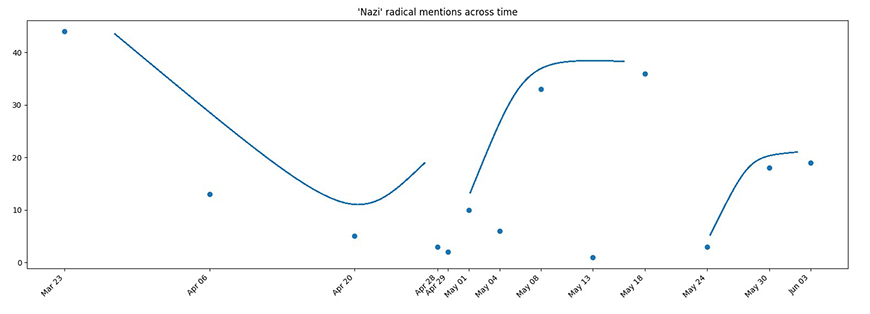

In the articles themselves, the terms like “Nazi”, “Nazism”, or “Nazification” create patterns of preference across time. In the beginning, in March, they were used more than 40 times in several articles, then it went down and up two times. Nevertheless, it never met the initial level again, losing around 10 quantity points at every drop. At the end of May, the Nazi-derived terms were used at the half of their March rate, only around 20 times:

By taking three separate articles, one from every time zone, when they dominated the language, this dropping pattern becomes more tangible.

Entitled “Why is the Ideology of Ukrainian Nationalism Assessed as Nazism in Russia?” this article from March 23rd has 1,249 words in total and 31 mentions of the Nazi-related terms (every 40th word).

Such terms are encountered in the contexts like “NSDAP measures for the Naziification of Germany” (мероприятия НСДАП по нацификации Германии), “relation between the Ukrainian nationalism and Nazi Germany” (отношение украинского национализма к гитлеровской Германии), “copied by Ukrainian nationalism from German Nazism” (скопирована украинским национализмом с немецкого нацизма), and “a Jew can be a Ukrainian nationalist-Nazi” (еврей может быть украинским националистом-нацистом).

Here is made an attempt to equate the Ukrainian nationalistic ideas to the Nazi Germany doctrine. This equating strategy is particularly efficient — it puts a sovereign country like Ukraine into a historical context whose war crimes and atrocities are still present in the European collective conscience.

Next, an article from May 18th, “Regiment “Azov”: Laboratory of Fascism,” which is 3,540-words-long, contains 33 Nazi-related terms (every 107th word).

They appear in phrases like “neo-Nazis, anti-semites and racists” (неонацисты, антисемиты и расисты), “attracting radicals and neo-Nazis into Azov” (привлекает в “Азов” радикалов и неонацистов), “neo-Nazi with the emblem of the Azov Regiment” (неонацист с эмблемой полка “Азов”), and “disgusting Nazi formation” (омерзительным нацистским формированием).

While still linked to Nazism, a new connotation is used here, that of neo-Nazism. The definition of this term can be viewed as less transparent, since it is not related to clear historical phenomena, like in the previous article. Here is an ideological novelty, as if Ukraine represented the logical evolution of German Nazism.

Finally, published on June 3rd, “Satanism and Occultism have become the Ideology of the Ukrainian National Battalions.” The article is 3,247-words-long and contains 20 Nazi-related terms (every 162nd word).

The contexts where they occur are “occultism in Nazi Germany” (оккультизм в нацистской Германии), “neo-Nazi-satanist movements” (неонацистко-сатанистские движения), and “esoteric Nazism” (эзотерический нацизм).

Ritualistic occultism emerges in these contexts, yet the article’s content continues to underline neo-Nazi notions presented previously. Every new article and, with it, every new point of view places itself around the semantic core of “Nazi,” then refines its semantic message, first by stating that Ukraine’s nationalism is inspired by Nazi Germany, then by saying that Ukraine’s kind of Nazism is new, with the Third Reich still at its foundation, and finally by expressing the idea that occultism and satanism are the primary constituents of Ukrainian Nazism.

With every new article though, the core Nazi message dissipates further into background. It demonstrates that, as pointed out above, the average Nazi-related terms usage drops across time, appearing every 40th, then every 107th, and finally every 162nd word. This animated word cloud takes into consideration that behavior, extracting the most important words per article, with the Nazi-related terms underlined in red. With time passing, they appear smaller and less significant overall.

Fluctuations in Russian Propaganda

“Repeat a lie often enough and it becomes the truth”; that is one of the methods of Russian propaganda, called, ironically, the Goebbels method. “Ukrainians are all Nazis and Russians are there to save them”; that is a fact repeated in different shapes and forms across RIA Novosti’s comments. Russian propaganda works.

RIA Novosti uses Nazi-derived words less and less, which is indicative of them shifting to new narratives. Those narratives are nevertheless complementary to the core message — Ukrainians are Nazis — but they are also neo-Nazis, and satanists. So, Russian propaganda also lives, it changes, creates comfortable stories, adapts itself to new contexts.

In our digital age, when information and disinformation are accumulating every second to be preserved in all of their triteness, the human brain relies even more on mental shortcuts when processing news. It goes to such an extent that if the political agenda of pro-Russian media changes, everything changes: in a fraction of a second, Putin can become an enemy of the people, the West the best ally, and so on.

The only working remedy to fake news and disinformation is not debunking, but prebunking, not repairing the damage, but preventing it. Russian propaganda has mastered the ways to counter debunking, like fake cures. Prebunking, on the other hand, focuses on spreading awareness that politically motivated groups could attempt to mislead the public on topics like the war in Ukraine.

Once the doubt is there, nothing is taken at face value. Consume news with a grain of salt, and stay aware of propaganda’s strategies. The truth is earned by methodically countering them.

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com