World Oil Transit Chokepoints – Analysis

By EIA

Chokepoints are narrow channels along widely used global sea routes, some so narrow that restrictions are placed on the size of the vessel that can navigate through them. They are a critical part of global energy security due to the high volume of oil traded through their narrow straits.

In 2011, total world oil production amounted to approximately 87 million barrels per day (bbl/d), and over one-half was moved by tankers on fixed maritime routes.

By volume of oil transit, the Strait of Hormuz, leading out of the Persian Gulf, and the Strait of Malacca, linking the Indian and Pacific Oceans, are two of the world’s most strategic chokepoints.

The international energy market is dependent upon reliable transport. The blockage of a chokepoint, even temporarily, can lead to substantial increases in total energy costs.

In addition, chokepoints leave oil tankers vulnerable to theft from pirates, terrorist attacks, and political unrest in the form of wars or hostilities as well as shipping accidents that can lead to disastrous oil spills. The seven straits highlighted in this brief serve as major trade routes for global oil transportation, and disruptions to shipments would affect oil prices and add thousands of miles of transit in an alternative direction, if even available.

Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz is by far the world’s most important chokepoint with an oil flow of about 17 million barrels per day in 2011.

Located between Oman and Iran, the Strait of Hormuz connects the Persian Gulf with the Gulf of Oman and the Arabian Sea. The Strait of Hormuz is the world’s most important oil chokepoint due to its daily oil flow of about 17 million bbl/d in 2011, up from between 15.7-15.9 million bbl/d in 2009-2010. Flows through the Strait in 2011 were roughly 35 percent of all seaborne traded oil, or almost 20 percent of oil traded worldwide. More than 85 percent of these crude oil exports went to Asian markets, with Japan, India, South Korea, and China representing the largest destinations. In addition, Qatar exports about 2 trillion cubic feet per year of liquefied natural gas (LNG) through the Strait of Hormuz, accounting for almost 20 percent of global LNG trade. Furthermore, Kuwait imports LNG volumes that travel northward through the Strait of Hormuz. These flows totaled about 100 billion cubic feet per year in 2010.

At its narrowest point, the Strait is 21 miles wide, but the width of the shipping lane in either direction is only two miles, separated by a two-mile buffer zone. The Strait is deep and wide enough to handle the world’s largest crude oil tankers, with about two-thirds of oil shipments carried by tankers in excess of 150,000 deadweight tons.

Most potential options to bypass Hormuz are currently not operational. Only Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) presently have pipelines able to ship crude oil outside of the Gulf, and only the latter two countries currently have additional pipeline capacity to circumvent Hormuz. At the start of 2012, the total available pipeline capacity from the two countries combined, which is not utilized, was approximately 1 million bbl/d. The amount could potentially increase to 4.3 million bbl/d by the end of this year, as both countries have recently completed steps to increase standby pipeline capacity to bypass the Strait.

Iraq has one major crude oil pipeline, the Kirkuk-Ceyhan (Iraq-Turkey) Pipeline that transports oil from the north of Iraq to the Turkish Mediterranean port of Ceyhan. This pipeline pumped about 0.4 million bbl/d in 2011, far below its nameplate capacity of 1.6 million bbl/d and it has been the target of sabotage attacks. Moreover, this pipeline cannot send additional volumes to bypass the Strait of Hormuz unless it receives oil from southern Iraq via the Strategic Pipeline, which links northern and southern Iraq. Currently, portions of the Strategic Pipeline are closed, and renovations to the Strategic Pipeline could take several years to complete.

Saudi Arabia has the 745-mile-long Petroline, also known as the East-West Pipeline, which runs from across Saudi Arabia from its Abqaiq complex to the Red Sea. The Petroline system consists of two pipelines with a total nameplate capacity of about 4.8 million bbl/d. The 56-inch pipeline has a nameplate capacity of 3 million bbl/d and its current throughput is about 2 million bbl/d. The 48-inch pipeline had been operating in recent years as a natural gas pipeline, but Saudi Arabia recently converted it back to an oil pipeline. The switch could increase Saudi Arabia’s spare oil pipeline capacity to bypass the Strait of Hormuz from 1 million bbl/d to 2.8 million bbl/d, which is only attainable if the system is able to operate at its full nameplate capacity.

The UAE constructed a 1.5 million bbl/d Abu Dhabi Crude Oil Pipeline that runs from Habshan, a collection point for Abu Dhabi’s onshore oil fields, to the port of Fujairah on the Gulf of Oman, allowing crude oil shipments to circumvent Hormuz. The pipeline was recently opened and the first shipment of 500,000 barrels of oil was sent through the pipeline to the Fujairah oil terminal where it was loaded on a tanker and sent to the Pak-Arab Refinery in Pakistan. The pipeline will be able to export up to 1.5 million bb/d, or more than half of UAE’s total net oil exports, once it reaches full operational capacity in the near future. However, the UAE does not currently have the ability to utilize this pipeline completely, until it ramps to full capacity. In late May, Fujairah ruler Sheikh Hamad bin Mohammed Al-Sharqi noted that this pipeline capacity could rise further to a maximum 1.8 million bbl/d.

Currently Operable Pipelines that are Unavailable as Bypass Options

Saudi Arabia also has two additional pipelines that run parallel to the Petroline system and bypass the Strait of Hormuz, but neither of them have the ability to transport additional volumes of oil should the Strait of Hormuz be closed. The Abqaiq-Yanbu natural gas liquids pipeline has a capacity of 290,000 bbl/d and is running at capacity. The IPSA (Iraqi Pipeline through Saudi Arabia) is used to transport natural gas to Saudi Arabia’s western coast. It was originally built to carry 1.65 million bbl/d of crude oil from Iraq to the Red Sea, but Saudi Arabia later converted it to carry natural gas, and has not announced plans to convert it back to transport crude oil.

Other pipelines, such as the Trans-Arabian Pipeline (TAPLINE) running from Qaisumah in Saudi Arabia to Sidon in Lebanon, have been out of service for years due to war damage, disuse, or political disagreements, and would require a complete renovation before being usable. Relatively small quantities, several hundred thousand barrels per day at most, could be trucked to mitigate closure of the Strait of Hormuz.

Malacca

The Strait of Malacca, linking the Indian and Pacific Oceans, is the shortest sea route between the Middle East and growing Asian markets.

The Strait of Malacca, located between Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, links the Indian Ocean to the South China Sea and Pacific Ocean. Malacca is the shortest sea route between Persian Gulf suppliers and the Asian markets—notably China, Japan, South Korea, and the Pacific Rim. Oil shipments through the Strait of Malacca supply China and Indonesia, two of the world’s fastest growing economies. It is the key chokepoint in Asia with an estimated 15.2 million bbl/d flow in 2011, compared to 13.8 million bbl/d in 2007. Crude oil makes up about 90 percent of flows, with the remainder being petroleum products.

At its narrowest point in the Phillips Channel of the Singapore Strait, Malacca is only 1.7 miles wide creating a natural bottleneck, as well as potential for collisions, grounding, or oil spills. According to the International Maritime Bureau’s Piracy Reporting Centre, piracy, including attempted theft and hijackings, is a constant threat to tankers in the Strait of Malacca, although the number of attacks has dropped due to the increased patrols by the littoral states’ authorities since July 2005.

Over 60,000 vessels transit the Strait of Malacca per year. If the strait were blocked, nearly half of the world’s fleet would be required to reroute around the Indonesian archipelago through Lombok Strait, located between the islands of Bali and Lombok, or the Sunda Strait, located between Java and Sumatra.

There have been several proposals to build bypass options and reduce tanker traffic through the Strait of Malacca, but most have not been followed through. China is on schedule to complete the Myanmar-China Oil and Gas Pipeline in 2013, two parallel oil and gas pipelines that stretch from Myanmar’s ports in the Bay of Bengal to the Yunnan province of China. The oil pipeline will be an alternative transport route for crude oil imports from the Middle East to potentially bypass the Strait of Malacca. The oil pipeline capacity is expected to reach about 440,000 bbl/d.

Suez Canal/SUMED Pipeline

The Suez Canal and SUMED Pipeline are strategic routes for Persian Gulf oil shipments to Europe. Closure of the Suez Canal and SUMED Pipeline would add an estimated 6,000 miles of transit around the continent of Africa.

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal is located in Egypt, and connects the Red Sea and Gulf of Suez with the Mediterranean Sea, spanning 120 miles. In 2011, petroleum (both crude oil and refined products) and liquefied natural gas (LNG) accounted for 15 and 6 percent of Suez cargoes, measured by cargo tonnage, respectively.

In 2011, 17,799 ships transited the Suez Canal from both directions, of which 20 percent were petroleum tankers and 6 percent were LNG tankers. Only 1,000 feet wide at its narrowest point, the Canal is unable to handle Ultra Large Crude Carriers (ULCC) and most fully laden Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCC) class crude oil tankers. The table above shows weight and capacity for the different tanker types. The Suezmax was the largest ship capable of navigating through the Canal until 2010 when the Suez Canal Authority extended the depth to 66 feet to allow over 60 percent of all tankers to use the Canal, including ships that are 220,000 of dead weight tons in size.

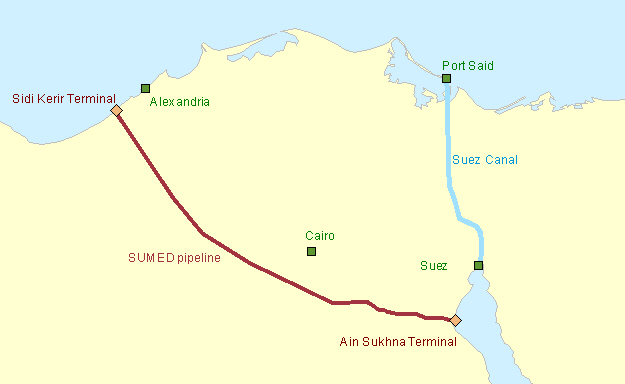

SUMED Pipeline

The 200-mile long SUMED Pipeline, or Suez-Mediterranean Pipeline, provides an alternative to the Suez Canal for those cargos too large to transit through the Canal (laden VLCCs and larger). The crude oil flows through two parallel pipelines that are 42-inches in diameter, with a total pipeline capacity of around 2.4 million bbl/d. Oil flows north through Egypt, and is carried from the Ain Sukhna onshore terminal on the Red Sea coast to its end point at the Sidi Kerir terminal on the Mediterranean. The SUMED is owned by Arab Petroleum Pipeline Co., a joint venture between the Egyptian General Petroleum Corporation (EGPC), Saudi Aramco, Abu Dhabi’s National Oil Company (ADNOC), and Kuwaiti companies.

The SUMED Pipeline is the only alternative route to transport crude oil from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean if ships were unable to navigate through the Suez Canal. Closure of the Suez Canal and the SUMED Pipeline would divert oil tankers around the southern tip of Africa, the Cape of Good Hope, adding approximately 6,000 miles to transit, increasing both costs and shipping time. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), shipping around Africa would add 15 days of transit to Europe and 8-10 days to the United States.

Fully laden VLCCs transiting toward the Suez Canal also use the SUMED Pipeline for lightering. Lightering occurs when a vessel needs to reduce its weight and draft by offloading cargo in order to enter a restrictive waterway, such as a canal. The Suez Canal is not deep enough to withstand a fully laden VLCC and, therefore, a portion of the crude is offloaded at the SUMED Pipeline at the Ain Sukhna terminal. The now partially laden VLCC then goes through the Suez Canal and picks up the portion of its crude at the other end of the pipeline, which is the Sidi Kerir terminal.

Crude Oil

The majority of crude oil transiting the Suez Canal travels northbound, towards markets in the Mediterranean and North America. Northbound canal flows averaged approximately 535,000 bbl/d of crude oil in 2011. The SUMED Pipeline accounted for about 1.7 million bbl/d of crude oil flows from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean over that same period. Combined, these two transit points were responsible for nearly 2.2 million bbl/d of crude oil flows into the Mediterranean. Northbound crude transit has declined by almost half since its level in 2008 when 943,000 bbl/d of crude transited northbound through the Canal and an additional 2.1 million bbl/d of crude travelled through the SUMED to the Mediterranean. Contrarily, crude oil shipments travelling southbound through the Canal toward the Red Sea, primarily destined for Asian markets, increased from 2008 through 2010, but fell slightly in 2011.

Total Oil and Products

Total oil flows from the Suez Canal declined steeply by more than one-third in 2009 to about 1.8 million bbl/d, down from 2008 levels of over 2.4 million bbl/d. Crude oil flows through the SUMED experienced a much steeper drop to1.2 million bbl/d from approximately 2.1 million bbl/d over the same period. The year-over-year difference reflects the collapse in world oil market demand that began in the fourth quarter of 2008, followed by OPEC production cuts (primarily from the Persian Gulf), which caused a sharp fall in regional oil trade starting in January 2009. Drops in transit also illustrate the changing dynamics of international oil markets where Asian demand is increasing at a higher rate than European and U.S. markets, and West African crude production is meeting a greater share of the latter’s demand. At the same time, piracy and security concerns around the Horn of Africa have led some exporters to travel the extra distance around South Africa to reach West African markets. Total oil flows through the Suez Canal increased year-over year to almost 2.2 million bbl/d in 2011, but still remain below previous levels prior to the global economic downturn.

Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG)

Unlike oil, LNG transit through the Suez Canal has been on the rise since 2008, with the total number of laden tankers increasing from approximately 210 to over 500, and volumes of LNG traveling northbound (laden tankers) increasing nearly six-fold. Southbound LNG transit originates in Algeria and Egypt, destined for Asian markets while northbound transit is mostly from Qatar and Oman, destined for European and North American markets. The rapid growth in LNG flows over the period represents the startup of five LNG trains in Qatar in 2009-2010. The only alternate route for LNG tankers would be around Africa as there is no pipeline infrastructure to offset any Suez Canal disruptions. Countries such as the United Kingdom, Belgium, and Italy received over 80 percent their total LNG imports via the Suez Canal in 2010, while Turkey, France, and the United States had about a quarter of their LNG imports transited through the Canal.

Bab el-Mandab

Closure of the Bab el-Mandab could keep tankers from the Persian Gulf from reaching the Suez Canal and Sumed Pipeline, diverting them around the southern tip of Africa.

The Bab el-Mandab is a chokepoint between the Horn of Africa and the Middle East, and a strategic link between the Mediterranean Sea and Indian Ocean. It is located between Yemen, Djibouti, and Eritrea, and connects the Red Sea with the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea. Most exports from the Persian Gulf that transit the Suez Canal and SUMED Pipeline also pass through the Bab el-Mandab.

An estimated 3.4 million bbl/d flowed through this waterway in 2011 toward Europe, the United States, and Asia, a drop from 4.5 million bbl/d in 2008, but an increase from 2.9 million bbl/d in 2009. Oil shipped through the strait decreased by almost one-third in 2009 as a result of the global economic downturn and the decline in northbound oil shipments to Europe. Northbound traffic through the Suez Canal and SUMED Pipeline also reflects the adverse affects of the global economic crisis in 2009 and 2010, when total oil flows through the complex declined significantly, as noted in the previous section. Northbound oil shipments increased through Bab el-Mandab in 2011 and over half of the traffic, about 2.0 million bbl/d, moved northbound en route to the Suez Canal and SUMED Pipeline.

The Bab el-Mandab is 18 miles wide at its narrowest point, making tanker traffic difficult and limited to two 2-mile-wide channels for inbound and outbound shipments. Closure of the Strait could keep tankers from the Persian Gulf from reaching the Suez Canal or SUMED Pipeline, diverting them around the southern tip of Africa, adding to transit time and cost. In addition, closure of the Bab el-Mandab would mean that oil entering the Red Sea from Sudan and other countries could no longer take the most direct route to Asian markets. This oil would instead have to go north into the Mediterranean Sea through other potential chokepoints, such as the Suez Canal and SUMED Pipeline.

Security became a concern of foreign firms doing business in the region, after a French tanker was attacked off the coast of Yemen by terrorists in October 2002. In recent years, this region has also seen rising piracy, and Somali pirates continue to attack vessels off the northern Somali coast in the Gulf of Aden and southern Red Sea including the Bab el-Mandab.

Turkish Straits

Increased oil exports from the Caspian Sea region make the Turkish Straits one of the busiest and most dangerous chokepoints in the world supplying Western and Southern Europe.

The Bosporus and Dardanelles are the Turkish Straits and divide Asia from Europe. The Bosporus is a 17-mile long waterway that connects the Black Sea with the Sea of Marmara, and the Dardanelles is a 40-mile long waterway that links the Sea of Marmara with the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas. Both are located in Turkey and supply Western and Southern Europe with oil from the Caspian Sea Region.

An estimated 2.9 million bbl/d flowed through the Turkish Straits in 2010, almost all of which was crude oil. The ports of the Black Sea are one of the primary oil export routes for Russia and other former Soviet Union republics. Oil shipments through the Turkish Straits decreased from over 3.4 million bbl/d at its peak in 2004 to 2.6 million bbl/d in 2006 as Russia shifted crude oil exports toward the Baltic ports. Traffic through the Straits increased again as crude production and exports from Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan rose in recent years.

Only half a mile wide at its narrowest point, the Turkish Straits are one of the world’s most difficult waterways to navigate due to its sinuous geography. With 50,000 vessels, including 5,500 oil tankers, passing through the straits annually it is also one of the world’s busiest chokepoints.

Turkey has raised concerns over the navigational safety and environmental threats to the Straits. Commercial shipping has the right of free passage through the Turkish Straits in peacetime, although Turkey claims the right to impose regulations for safety and environmental purposes. Bottlenecks and heavy traffic also create problems for oil tankers in the Turkish Straits. While there are no current alternate routes for westward shipments from the Black and Caspian Sea region, there are several pipeline projects in various phases of development underway.

Panama Canal

The United States is the top country of origin and destination for all commodities transiting through the Panama Canal; however, it is not a significant route for U.S. petroleum trade.

The Panama Canal is an important route connecting the Pacific Ocean with the Caribbean Sea and Atlantic Ocean. The Canal is 50 miles long, and only 110 feet wide at its narrowest point called Culebra Cut on the Continental Divide. Over 14,000 vessels transit the Canal annually, of which more than 60 percent (by tonnage) represent United States coast-to-coast trade, along with United States trade to and from the world that passed through the Panama Canal.

Closure of the Panama Canal would greatly increase transit times and costs adding over 8,000 miles of travel. Vessels would have to reroute around the Straits of Magellan, Cape Horn and Drake Passage under the tip of South America.

However, the Panama Canal is not a significant route for petroleum transit or for U. S. petroleum imports. Roughly one-fifth of the traffic through the canal (measured by both transits and tonnage) was by tankers. According to the Panama Canal Authority, 755,000 bbl/d of crude and petroleum products were transported through the canal in Fiscal Year 2011, of which 637,000 bbl/d were refined products, and the rest crude oil (EIA conversions from long tons to barrels). Nearly 80 percent of total petroleum, or 608,000 bbl/d, passed from north (Atlantic) to south (Pacific).

The relevance of the Panama Canal to the global oil trade has diminished, as many modern tankers are too large to travel through the canal. Some oil tankers, such as the ULCC (Ultra Large Crude Carriers) class tankers, can be nearly five times larger than the maximum capacity of the canal. The largest vessel that can transit the Panama Canal is known as a PANAMAX-size vessel (ships ranging from 60,000 â 100,000 dead weight tons in size and no wider than 108 ft.)

In order to make the canal more accessible, the Panama Canal Authority began an expansion program to be completed by the end of 2014. However, while many larger tankers will be able to transit the canal after 2014, some ULCCs will still be unable to make the transit. The Panama Canal Authority features a description of the expansion program and progress reports.

Trans-Panama Pipeline

The Trans-Panama Pipeline (TPP) is operated by Petroterminal de Panama, S.A. (PTP) and is located outside the former Canal Zone near the Costa Rican border. It runs from the port of Charco Azul on the Pacific Coast to the port of Chiriquie Grande in Bocas del Toro on the Caribbean. The pipeline was built in 1982, with the original purpose of facilitating crude oil shipments from Alaska’s North Slope to refineries in the Caribbean and the U.S. Gulf Coast. However, in 1996, the TPP was shut down as oil companies began shipping Alaskan crude along alternative routes. Since 1996, there were intermittent requests and proposals to utilize the TPP. In August 2009, TPP completed a project to reverse its flows in order to enable it to carry oil from the Caribbean to the Pacific. The pipeline’s current capacity is about 600,000 bbl/d.

BP and PTP recently signed a seven-year transportation and storage agreement, allowing BP to lease storage located on the Caribbean and Pacific coasts of Panama and to use the pipeline to transport crude oil to U.S. West Coast refiners. According to PTP, BP has leased 5.4 million barrels of PTP’s storage and committed to east-to-west oil shipments through the pipeline averaging 100,000 b/d. BP started shipping crude oil through the TPP earlier this year. The route reduces transport time and costs of ships having to go around Cape Horn at the tip of South America to get to the U.S. West Coast.

Danish Straits

The Danish Straits are becoming an increasingly important route for Russian oil exports to Europe.

About 3 million bbl/d flowed through this waterway in 2010, with most of this flowing westwards.

Russia has increasingly been shifting its crude oil exports to its Baltic ports, especially the relatively new port of Primorsk, which accounted for half of the exports through the Straits.

An estimated 0.3 million bbl/d of crude oil, primarily from Norway, flowed eastward to Scandinavian markets.

About one-third of the westward exports through the Straits are for refined products, coming from Baltic Sea ports such as Tallinn (Muuga), Venstpils, and St. Petersburg.