Europe And Morocco: Aspects Of Inter-Cultural Communication And Human Exchange – Analysis

Definition Of The Concept

Cultures are not isolated and static sets of customs, rituals, beliefs and practices, they are living phenomena that need input from other cultures to live and prosper, and experience has shown that those cultures that choose isolation, as a way of life, definitely do not disappear but do remain, somewhat, handicapped.

Over centuries of human history, cultures have entered into collision with other cultures, either through wars, invasions or annexation but they have never died out completely as long as people who represent them are still in life, a good example of that is the Red Indians, who after being decimated by the US Army in the 19th century have been parked in reserves with the idea of assimilating them to the all-powerful American culture. But, though many Red Indians have over decades assimilated to the American way of life, yet the majority clings to their culture because it is a symbol of their identity. And one of the main reasons for which cultures survive even in the most adverse environments is the fact that they are potent symbols of identity.

According to Samuel Huntington,i as argued in his controversial article entitled “The Clash of Civilizations?”, the next century will see a clash between the three main civilisations of the world, i.e. Western, Islamic and Confucian or rather, and that is what is the writer was driving at,: a clash between the Western and the Islamic civilisations. This demonization of Islam is may be the result of the end of the Cold War which left an uncomfortable threat “vacuum:.ii

For some Islamists like Benkirane,iii a moderate Islamic leader of the group Adalah wa Tanmiya, the Western world cannot live and prosper in the absence of a potential enemy. Yesterday it was Communism and today it is Islam and if there were not Islam, they would have had to create an enemy of some sort.

It is a known fact that ideologies, political systems, political philosophies, religions do clash quite often, but cultures iv do not and they manage to co-exist even in the most adverse situations. In fact, even in the most critical situations, cultures manage to set up extraordinary channels for communication and exchange between themselves.

Historical Background

As far as human memory can go back, Europe and the Mediterranean Region have had a very long record of exchange and communication as well as conflict and misunderstanding. Indeed, throughout known history the populations of these two regions visited, lived, traded and made exchanges with each other but also fought, invaded and massacred each other. And today, in spite of centuries of exchanges both peaceful and violent, these two regions stand far apart, unable to benefit from their long common history. The question that comes to mind right away is: why this situation then and now?

Obviously there is no straight down to earth answer to this complex question, maybe the answer is the whole record of history itself and not specific aspects or parts of it. However, there are two main factors that have been instrumental in bringing together and setting apart the two regions: these are religious and ideological beliefs and commercial interests.

The Roman Period

During the Roman Empire, North Africa and the Middle East, which were outside of the Roman control and influence, axis romanus, were conquered by the force of the sword around 146 to 40 BC and brought within the fold of the empire. The Romans imposed on the population their language, their beliefs and way of life and even the urban centres were built within the norms of the Roman architecture, i.e. Volibilus, Lixus, Sbeitla, Dougga, etc.

The Berbers of North Africa, who by the way call themselves Imazighen, “free and noble people”, and their language Tamazight, were given the name Berber by the Romans who called them barbarus i.e. people who live outside the axis romanus and who are not civilised, in other words – barbarians.

In the administration of the territories of North Africa, the Romans were extremely flexible in their approach; they allowed the indigenous people to hold important positions in the administration and in the army as indicated by E. Guernier:v

Un fait parait dominer toute l’administration romaine: une extrême souplesse dans l’application des mesures législatives et des règlements. D’autre part, une place importante est faite aux indigènes dans les rouages impériaux aussi bien dans l’administration civile que dans les cadres militaires.

Economically speaking, the Roman colonisation did not improve the living conditions of the population that was in its majority made of peasants, already under Carthaginian rule the North Africans were used to the techniques of the cultivation of wheat, barley, vines and olive trees which are still somewhat the basic crops of the area today.

However, the most remarkable achievement of the Romans in the area is undoubtedly the introduction of sophisticated irrigation systems and techniquesvi. They built aqueducts for the cities, cisterns for the farms and artesian wells for the oases. The most well-known irrigation works the Romans left behind are: the aqueduct of Carthage and that of Cherchell, the dam of Kasserine and the cisterns of Cirta and Hippone. The Romans, also, taught the locals techniques to collect rain water in valleys in order to use for agriculture, when needed, and to build irrigation ditches along rivers and streams to use the water for the neighbouring lands.

It is, also, a known fact that the Roman legion had in its ranks many engineers who provided advice and, also, built underground canals like the one in Bougie. It is thanks to the experience of the Romans that Berbers developed their own techniques in irrigation such as the famous khettara-s in the plain of Marrakech and the water towers that organise the distribution of water along the two sides of the Atlas chain of mountains.

The Romans, also, built several roads to secure the control of the territories and allow the exchange of goods between the people. Some of the known roads of the time are:

- The Carthage-Thevest road 275 km long; and

- The Carthage-Tripoli road 823 km long.

These roads necessitated a good knowledge of bridge building over rivers and streams and wadi-s.

Among the other Roman influences still present with the population of North Africa is a certain obsession with cleanliness. Indeed, the Romans built baths everywhere, and encouraged people to bathe frequently, and they made out of them public places of intellectual discussion and commercial transactions and political lobbying.

The Romans, also, washed excessively before, between and after meals. Indeed, slaves passed between the beds on which lie their masters and guests and poured on their fingers fresh perfumed water.vii

Later on, when the Muslims arrived they had no problem, as they did in some other areas, in introducing the concept of cleanliness and the idea of ablutions before prayer. Today, it is a common practice in North Africa to offer guests, on arrival, to freshen up and, also, to wash before and after meals.

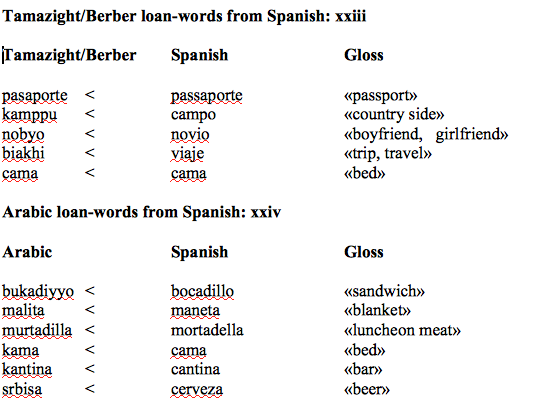

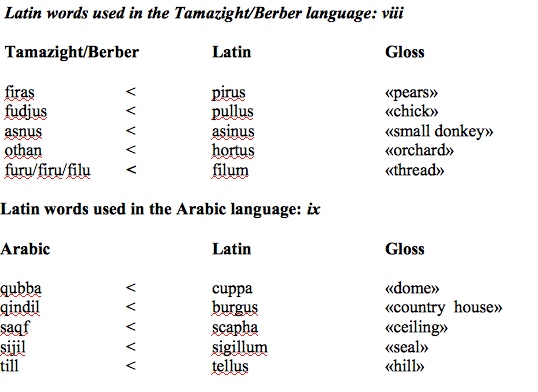

The influence of the Roman civilisation on North Africa is also present in both Berber and Arabic languages as shown by the following examples:

Among the celebrations and the rituals still common in North Africa and especially in Morocco, there is the Boujloudia known in Berber as bou-ihidorn, bou-ilmawen or bou-isrikhen x that often takes place during the religious celebration of l-aid l-kbir, “the feast of sacrifice”. On the first day of the feast, a ram is ritually slaughtered in remembrance of God’s request made to Abraham in a dream to sacrifice his son Ismail to him.

Among the celebrations and the rituals still common in North Africa and especially in Morocco, there is the Boujloudia known in Berber as bou-ihidorn, bou-ilmawen or bou-isrikhen x that often takes place during the religious celebration of l-aid l-kbir, “the feast of sacrifice”. On the first day of the feast, a ram is ritually slaughtered in remembrance of God’s request made to Abraham in a dream to sacrifice his son Ismail to him.

In fact, this practice is quite common in many areas in Morocco and in some parts of Algeria and Tunisia and its existence is traced back to ancient Greece and ancient Rome. It used to take place in the summer at the end of the agricultural cycle, when the crops have been reaped, as gesture of thanksgiving to the gods for their generosity and a prayer for more fertility for the coming year.

However, in the Jbala region of north-western Morocco, in the village of Tatoft among Ahl Srif, an arabised Berber clan, there is a professional group of musicians known as the Master Musicians of Jahjouka who have given the rites of Bou Jelloud xi a special significance because they believe that their rites hark back to pre-Islamic times and derive from the rites of Pan.xii Their origins stem from Greek and Roman influences and correspond – in the wild chase of Bou-Jelloud (the father of skins), the instigator of a fertility dance – to various fertility traditions found in most Mediterranean countries.

There is even a reference to this tradition in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar (Act 1, Scene 2):

Forget not,

In your haste, Antonuis,

To touch Calpurnia,

For our elders say

The barren touched in the holy chase

Shake off their sterile curse

Even today, the ceremony still involves Bou Jelloud, emerging from his place of concealment on hearing the sounds of ghaita-s xiii, and dancing himself into a trance while flailing women with branches to make them fertile.

The location of these rites is a small village situated in the Jbala region of Northern Morocco, in the piedmont region leading, further east, into the mountains of the Rif. The village of Jahjouka is still the home of Pan, the goat like god and his persisting presence is a challenge to time space and religion.

The tradition emerged from Egypt and, despite transformations of nomenclature and culture it has been transmogrified into the practices of the Master Musicians and their practice of the Pipes of Pan. A crucial factor in this development was the fact that the introduction of Islam in the Jbala region did not destroy the pre-existing traditions. Islam was introduced in 800 AD by the eastern mystic, Sidi Ahmed Sheikh, who allowed local practice to continue unhindered and even managed to dignify it by granting it Baraka,xiv The musicians involved were, therefore, able to depend on their music to earn their living.

Today, the musicians receive a tithe – ziyara – from local people for their music and it is this on which they survive. In return they play ghaita music in the courtyard of Sidi Ahmed Sheikh’s shrine, which is located in the village of Jahjouka. Visitors come to the shrine – kubba – every Friday to seek baraka from the saint. The musicians, also, fulfil a psycho-medical function for they cure the sick and those with medical disorders. Those afflicted are tied to a tree in the courtyard of the shrine and the ghaita and tbel xv are played by the musicians to drive out the demons supposed to be responsible for the illness- whether physical or mental.

The major celebration in Jahjouka is the Pan festival which takes place during l-aid l-kbir.xvi For the ten days of the feast, local villagers attend the musical celebrations and participate in its climax, when Bou Jelloud emerges from his cave to seek out according to the myth, his lover – Aisha l-hamqa, “crazy Aisha” – identified by her goat like feet (a typical attribute of female in Morocco). Bou Jelloud’s arrival in the area before the shrine is heralded by the screams of women and children whom he flails as he passes by — a feature that recalls some of the traditions of religious brotherhoods such as Hmadsha xvii and Aissawa.

The Pan festival is not the only cultural practice and ritual inherited from ancient Greece and ancient Rome and still is in use in the popular culture of North Africa, we find such bizarre rituals as dancing around fires and jumping over them as well as throwing buckets of water at passersby during the celebration of the Islamic New Year – Fatih Muharram.

What this means in other words, is that inter-cultural communication and exchange between North Africa and the ancient civilisations of Europe were so strong that subsequent civilisations and religions have been unable to erase them from the memory of the local population. On the contrary, Islam aware of their appeal to the people attempted to Islamic most rituals by introducing Islamic concepts in them as is the case with the Pan festival in which the character of the Haj, “Muslim pilgrim”, dressed in white, dances around aimlessly while Bou Jelloud runs after his lover Aisha l-Hamqa.

The Arabs In Spain

Many centuries later, the Arabs returned the Roman courtesy by paying Europe a visit that was to last some eight centuries. Indeed, in 711, Musa Ibn Nusayr, then Arab Governor of North Africa, on learning that King Roderick, the last Goth king, was busy in the north subduing rebellious Basques, dispatched one of his able generals the Berber Tarik Ibn Ziyad at the command of an army of 7,000 Berber soldiers to make a raid on Andalusia.xviii Tarik landed at the lion’s rock which was to be named after him since: Jabal Tarik (Tarik’s mountain) or Gibraltar and disobeying his commander burned his ships and made his famous speech:

The sea is at your back,

The enemy is in front of you

And all that is left for you to do

Is to push forward and die in the name of Allah

It might be true that the Arabs conquered Spain by the sword, but it is universally admitted that their presence in this part of Europe brought prosperity, knowledge, culture and refinement to this country and the whole of Europe and was instrumental in its renaissance. This is corroborated by S. Lane-Pool in his book entitled The Moors in Spain published in 1887: xix

“The history of Spain offers us a melancholy contrast. Twelve hundred years ago, Tarik the Moor added the land of the Visigoths to the long catalogue of kingdoms subdued by the Moslems. For nearly eight centuries, under the Mohammedan rulers, Spain set to all Europe a shining example of a civilized and enlightened State. Her fertile provinces, rendered doubly prolific by the industry and engineering skill of her conquerors, bore fruit and hundredfold. Cities innumerable sprang up in the rich valleys of the Guadelquivir and the Guadiana, whose names, and names only, still commemorate the vanished glories of their past. Art, literature, and science prospered, as they then prospered nowhere else in Europe. Students flocked from France and Germany and England to drink from the fountain of learning which flowed only in the cities of the Moors. The surgeons and doctors of Andalusia were in the van of science: women were encouraged to devote themselves top serious study, and the lady doctor was not unknown among the people of Cordova. Mathematics, astronomy and botany, history, philosophy and jurisprudence were to be mastered in Spain, and Spain alone. the practical work of the field, the scientific methods of irrigation, the arts of fortification and shipbuilding, the highest and most elaborate products of the loom, the graver and the hammer, the potter’s wheel and the mason’s trowel, were brought to perfection by the Spanish Moors. In the practice of war no less than in the arts of peace they long stood supreme. Their fleets disputed the command of the Mediterranean with the Fatimites, while their armies carried fire and sword through the Christian marches. The Cid himself, the national hero, long fought on the Moorish side, and in all save education was more than half a Moor. Whatsoever makes a kingdom great and prosperous, whatsoever tends to refinement and civilization, was found in Moslem Spain.”

It goes without saying that the Arab-Islamic civilisation in Spain did not reach its apogee by the sheer might of the sword but on the contrary it owes its success to inter-cultural communication and exchange initiated by the Arabs. The Arab presence in Spain for eight centuries is undoubtedly the result of some sort of coexistence between people of different ethnic origins, cultures and religions. S. Lane-Poolexx argues that the Jews and the Moors and the Persians were instrumental in the development of Muslim Spain:

“Jew, wherever the arms of the Saracens penetrated, there we shall always find the Jews in close pursuit : while the Arab fought, the Jew trafficked, and when the fighting was over, and Moor and Persian joined in that cultivation of learning and philosophy, arts and sciences, which pre-eminently distinguished the rule of the Saracens in the Middle Ages.”

It is a known fact among historians that prior to the arrival of the Arabs to Spain, the Jews were persecuted,xxi especially during the Visigoth King Sisebut (612-21 AD), though in reality the legislation allowing discrimination against them had been passed earlier during the reign of Alaric II (484-507 AD) as a follow-up of the decisions of the third Council of Toledo approved by Reccared (586-601 AD), which forced Jews to convert to Christianity and forbade them to buy Christian slaves.

After the conquest of Spain by the Muslim forces was completed, the original inhabitants of the conquered land were given the choice between converting to Islam or remaining Christian with the status of dhimmi and be subjected to the payment of a poll tax known as jizya, and indeed many people preferred to stick to their Christian faith. A good illustration of the ideal inter-cultural communication that was set up by the Muslims then is the rise to power of many Christians within the bureaucratic and political structure of the Islamic state.xxii

As a result of the contact between the Muslims and the European inhabitants of the Iberian Peninsula, we still find today on either side of the of the Strait of Gibraltar traces of the civilisation of the other in cultural practises or in the language.

Indeed, one of the most famous dishes of Spain is paella which is made of rice, chicken meat and seafood. In the time of Muslim Spain, this was actually the dish of albaycin, the poor, (name given in Granada to a quarter which was inhabited by the poor) and which consisted of the remains al-baqiyya of the previous days. In the North African side, the Spanish word fiesta, “feast” pronounced fishta has a special meaning that no other word could describe, in spite of their abundance in the Arabic language: hafl,’ihtifal , ‘id, etc. because it refers back to the excessive celebrations of the Spaniards during the weekend, unknown elsewhere in either side of the Strait of Gibraltar. Another word which is of Spanish origin and has a special meaning in North African Arabic is the word gana, “mood, disposition, feeling, etc.”. Indeed this word is used in Arabic in various situations as shown by the following examples:

- tl°at li l-gana °lik

I am disposed to like you - ma °andi gana

I am in no good mood - huwwa u gantu

It is up to how he feels - kayjini °la ganti

We get along together

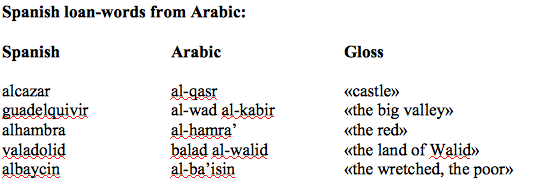

Because of the long inter-cultural interaction between the Arabs, the Berbers and the Spaniards, the languages of these people borrowed from each other:

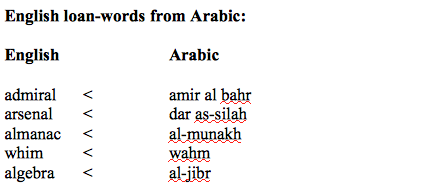

Through contact with other European cultures and languages in Muslim Spain, there took place an important word-borrowing on both sides. An important manifestation of this is the word- borrowing that took part in English as shown by the following examples:

The Image Of The Other

Representation of the Moor

In 1603-1604, Shakespeare (1564-1616) at the height of his career as a playwright produced Othello, the Moor of Venice, which the critics believe was based on a story in Giraldi Cinthio’s Hecatommithi (III, 7), a collection of some hundred plays published in Italy in the 16th century. It is believed that at this time there was no translation of this work in the English language and it is more likely that Shakespeare read the collection in its original version in Italian and may have also been exposed to the French language as translated by Gabriel Chappuys.xxv

The story from Giraldi Cinthio’s Hecatommithi, which inspired Shakespeare to write his tragedy Othello, is about a valiant and handsome Moor in Venice, who distinguished himself in battle against the Turks and this earned him much respect and recognition from the Signoria of the Republic in whose pay he was. Desdemona, a virtuous lady of great beauty, moved by his courage and valour fell in love with him. He returned her love vanquished by her ravishing beauty and nobility of character. Her parents, unhappy with the subject of her infatuation tried to convince her to change her mind, but in vain, because responding to her heart’s desire she ended up marrying the Moor.

Having decided to make a change in the troops stationed in Cyprus, the Signoria of Venice appointed Othello commander of the soldiers to be dispatched. For Othello this decision was a great honour bestowed upon him by the state, but it caused him at the same time great pain because he was going to be away from his beloved Desdemona. Having realised the true source of her husband’s pain and sadness, she revealed to him the extent of her love and affection. Relieved by what he heard and engulfed by her expressions of love for him, he left for Cyprus happy and content.

But it so happened, that Othello had in his soldiery a handsome man of tremendous wickedness and malice by the name of Ensign who was in the favour of the Moor. This man had great infatuation for Desdemona and was constantly plotting to make her fall with the Moor in order to gain her favour and affection. Among the brave and loyal men of Othello, there was a Captain for whom he had much affection and whom Desdemona liked as a consequence.

This Captain, on killing a guard with his sword was deprived by the Moor of his rank, troubled by what had happened Desdemona aware of her husband’s respect and friendship for the man, intervened in his favour. Ensign, who in his villainy and wickedness was waiting for such a propitious occasion, started leading purposefully the Moor to believe that her attempts to have him reintegrate the Captain were justified by her love for him. The web of villainy so neatly knitted by Ensign started to unfold slowly. Thus, Othello turned against his wife and began to treat her with much disdain and disrespect.

Once, while visiting Ensign’s wife, with whom she used to spend much time, Desdemona had an embroidered handkerchief, offered to her by Othello, stolen from her by the villain soldier and left at the Captain’s house. Having found the handkerchief, resolved to return it to its rightful owner, so he went to Desdemona’s house and knocked at the back door and Othello who had just returned home answered the door, fearing for his life the Captain fled before Othello opened the door. This incident increased the level of suspicion that the Moor had towards his wife’s faithfulness and allegiance to him. After consulting with Ensign, who further aroused his jealousy and hatred, he resolved to slay both his wife and the Captain in such a way that their death would not be attributed to him.

The Moor convinced Ensign to kill the Captain in return of a handsome reward while he would put Desdemona to death, but later changed his mind. Ensign attacked the Captain but only managed to cut off his leg. Having realised that Othello did not have enough courage to kill his wife, he suggested carrying out this dirty task by himself by beating her on her head with a sand back and attributing her death to the old ceiling of the room that he would pull down on her and pretext that it caved in. And this he did, but before dying Desdemona, not aware of the conspiracy, turned to her husband for help and her appeal was met with insults and disdain, having realised what had happened she appealed for the heavenly justice.

However, it did not take long for this justice to materialize, because right after Desdemona’s burial, the Moor whom she loved more than her life regretted his act and felt tremendous loss and sorrow as a consequence. Realising that it was Ensign who was responsible for much of his trouble, he resolved to kill him, but had it not been for his fear of the retribution of the Signoria of Venice he would have fulfilled his resolution gladly. Instead, he deprived him of his rank and had him moved away from his company. This incensed Ensign who decided to take revenge, so he first informed the Captain that it was the Moor who was behind his misfortune on the account of the suspicion he had formed of the conduct of his wife. On hearing this, the Captain went to the Signora and accused the Moor of the murder of his wife; the latter was brought before justice in Venice but would not confess in spite of torture. Later, he was thrown in jail where he was slain by his wife’s kinsmen.

As for Ensign, he returned to his country and following up on his mischief he accused one of his companions of inciting him to kill an enemy of his of a noble rank. This man was arrested and denied all accusations, even under torture, upon which Ensign was arrested and tortured to prove his accusations. Later, he was removed from prison and died in his house a horrible death.

Shakespeare’s version is not much different apart from a surgical change of some characters’ names and some facts. But with the great mastery that is his he managed to give the plot more flavour, the tragedy more suspense and the characters more life and more independence and reality.

In introducing this play, Alvin Kernan xxvi argues that Othello came about at the height of Shakespeare’s career as a playwright at a time when he acquired a better knowledge of humanity, its nature and its aspirations:

When Shakespeare wrote Othello, about 1604, his knowledge of human nature and his ability to dramatize it in language and action were at their height. The play offers, even in its minor characters, a number of unusually full and profound studies of humanity : Brabantio, the sophisticated, civilized Venetian senator, unable to comprehend that his delicate daughter could love and marry a Moor, speaking excitedly of black magic and spells to account for what his mind cannot understand; Cassio, the gentleman-soldier, polished in manners and gracious in bearing, wildly drunk and revealing a deeply rooted pride in his ramblings about senior officers being saved before their juniors; Emilia, the sensible and conventional waiting woman, making small talk about love and suddenly remarking that though she believes adultery to be wrong, still if the price were high enough she would sell- and so, she believes, would most women. The vision of human nature which the play offers is one of ancient terrors and primal drives – fear of the unknown, pride, greed, lust- underlying smooth, civilized surfaces- the noble senator, the competent and well-mannered lieutenant, the conventional gentlewoman.

Othello in its entirety is but a cultural representation of the other, the other here being the dark world of Islam symbolised by the black complexion of the Moor. Even if the Moor had converted to Christianity and had learned the ways of the civilised, he remained suspicious and barbaric and indeed at the height of his rage, Shakespeare makes him compare himself to the raging seas, savage and uncontrollable: xxvii

Like to the Pontic Sea,

Whose icy current and compulsive course

Nev’r keeps retiring ebb, but keeps due on

To the Propontic and the Hellespont,

Even so my bloody thoughts, with violent pace,

Shall nev’r look back, nev’r ebb to humble love?

Till that a capable and wide revenge

Swallow them up

In short, what Shakespeare means to say is that all the Moor can think about is violence and revenge and that is his true personality, his true nature and culture and for all of this he is but a genuine reflection of his people and their beliefs.

In this representation, the Moor is a brave soldier and an able commander and that is why beautiful Desdemona fell in love with him, but he is a fool and is considered by Iago as such and advises to treat him like an ass: xxviii

The Moor is of free and open nature, That thinks men honest that but seem to be so; And will as tenderly be led by th’ nose As asses are.

Iago, a man of lesser rank and valour but of tremendous intelligence manages to manipulate Othello, at will, and to work him up in such a rage of jealousy that he loses his wisdom and composure and murders his wife. Emilia, the wife of his villain attendant, enraged by his act speaks her mind and treats him like dirt:xxix

t pow’r to Thou hast not half thado me harm As I have to be hurt. O gull! O dolt! As ignorant as dirt! Thou hast done a deed.

Brabantio, Desdemona’s father, grieved by his daughter’s decision to marry the Moor, considers the marriage as being an act against nature. He lets free his deep feelings of racism and ethnocentrism by wondering why on earth his daughter agreed to marry “what” she feared most to look on: xxx

A maiden never bold,

Of spirit so still and quiet that her motion

Blushed at herself; and she, in spite of nature,

Of years, of country, credit, everything,

To fall in love with what she feared to look on!

It is a judgement maimed and most imperfect

That will confess perfection so could err

Against all rules of nature, and must be driven

To find out practices of cunning hell

Why this should be.

He believes the whole business of love and marriage to be the work of witchcraft and black magic, and like all the men of his time what they could not explain by the prevalent logic of the time is automatically attributed to the dark forces of magic: xxxi

I therefore vouch again

That with some mixtures pow’rful o’er the blood,

Or with some dram, conjured to this effect,

He wrought upon her.

For Brabantio, Desdemona did not choose to live with the Moor of her own free will. She does not control her actions; she is under a strong spell:xxxii

She is abused, stol’n from me, and corrupted

By spells and medicines bought of mountebanks

For nature so prepost’rously to err,

Being not deficient, blind, or lame of sense,

Sans witchcraft could not.

But the Moor is not only portrayed as savage, violent and uncivilised, he is also vulgar and vile, and when Iago went to the house of Brabantio to inform him that his daughter has taken Othello the Moor for husband, he described what happened in the most xenophobic and racist terms possible using terminology related to horses and equestrian life :xxxiii

You’ll have your daughter covered with a Barbary

horse, you’ll have your nephews neigh to you,

You’ll have coursers for cousins, and gennets for

germans.

He used the basest of metaphors and idioms to make reference to their betrothal and especially its physical aspect :xxxiv

I am one, sir that comes to tell you your daughter

and the Moor are making the beast with two backs.

Iago’s hatred for Othello, in particular, and for the Moors, in general, is incommensurable and he expresses his abhorrence of them in a monologue that could well express the general feeling that was prevalent in his time:xxxv

These Moors are changeable in their wills-fill thy purse with money. The food that to him now is as luscious as locusts shall be to him shortly as bitter as coloquintida. She must change for youth; when she is sated with his body, she will find the errors of her choice.

Therefore, put money in thy purse. If thou wilt needs damn thyself, do it a more delicate way than drowning. Make all the money thou canst. If sanctimony and a frail vow betwixt an erring barbarian and supersubtle Venetian be not too hard for my wits, and all the tribe of hell, thou shalt enjoy her.

In Shakespeare’s Othello, the Moor is valiant, courageous and faithful in his allegiance and he has proved that by rendering numerous services to the Signora of Venice as a military commander and that is why he was appointed to command the troops in Cyprus and confront the Turks. He is, also, of the Christian faith.

But, in spite of all these fine qualities and excellent attributes, he is violent, savage, barbaric and vile because the general feeling expressed by the playwright in his work is one of disgust and that seems to reflect the image the public opinion of that time had of people of darker complexions and foreign origins.

Racial superiority of the white Christian European over other races was a very important issue for the Elizabethan public as explained in what follows by Margaret Webster: xxxvi

“The question of racial division is of paramount importance to the play, to its credibility and to the validity of every character in it. There has been much controversy as to Shakespeare’s precise intention with regard to Othello’s race. It is improbable that he troubled himself greatly with ethnological exactness. The Moor, to an Elizabethan, was a blackamoor, an African, an Ethiopian. Shakespeare’s other Moor, Aaron, in TITUS ANDRONICUS, is specifically black; he has thick lips and a fleece of woolly hair. The Prince of Morocco in THE MERCHANT OF VENICE bears « the shadowed livery of the burnished sun, » and even Portia recoils from his « complexion » which he himself is at great pains to explain.”

As argued above, it did not matter much to the Elizabethan elite what the term Moorxxxvii stood for as long as it represented someone of “inferior” race and different religion as well as darker complexion, something close to the derogatory term wog used today by the British racists to refer to Arabs and sometimes aliens, in general, or the term basané or bicot used by the French racists to refer to Arabs, too, or to people with darker complexions.

We learn from this tragedy of the 17th century that Europe and the southern Mediterranean were at all times engaged in inter-cultural communication and exchange. A Moor from the Barbary States xxxviii, made his way to Venice, he even might have been fighting on the Ottoman side prior to joining the Venetian army, where he rose to the prominent position of commander. Being a Moor, it is more likely that originally he was a Muslim and later on converted to the Christian faith. It is likely, also, that he spoke Arabic or Berber or some other African language but managed later on to learn and converse easily and fluently in European tongues. He managed to mix with the aristocracy and the elite and that is how he managed to meet the ravishing Desdemona. Desdemona, on her part, did not bother neither about his colour nor his origin, she fell in love with him, because of his worth and courage and went on to marry him not worrying, in the least, about her father’s misgivings about the whole thing, for when asked to whom she owes allegiance most, her father or the Moor, she chose the latter:xxxix

My noble father,

I do perceive here a divided duty.

To you I am bound for life and education;

My life and education both do learn me

How to respect you. You are the lord of duty,

I am hitherto your daughter. But here’s my husband,

And so much duty as my mother showed

To you , preferring you before her father,

So much I challenge that I may profess

Due to the Moor my lord

In the council chamber, where the affairs of the state are debated, the Moor is held in much esteem, a proof of that are the terms of address used to call his attention by First Senator: xl

Here comes Brabantio and the valiant Moor

Even the Duke addresses the Moor with much respect:xli

Valiant Othello, we must straight employ you Against the general enemy Ottoman.

It is a well-established fact that love and affection know no boundary, no obstacle , do not owe allegiance to no religion, no ideology or race, no bias and no prejudice, but on the contrary they have always been ambassadors of goodwill and understanding. Love always brings people together and bridges gaps between cultures and civilisations. It is, perhaps, the best form of inter-cultural communication; it needs no words, no etiquette and no special occasion. It is spontaneous, direct and clear.

In the following verse, Othello describes to the council members of Venice, the circumstances in which Desdemona fell in love with him:xlii

Her father loved me; oft invited me;

Still questioned me the story of my life

From year to year, the battle, sieges, fortune

That I have passed.

I ran it through, even from my boyish days

To th’very moment that he bade me tell it.

Wherein I spoke of most disastrous chances,

Of moving accidents by flood and field,

Of hairbreadth scapes i’ th’imminent deadly breach,

Of being taken by the insolent foe

And sold to slavery, of my redemption thence

And portance in my travel’s history

Wherein of anters vast and deserts idle,

Rough quarries, rocks, and hills whose heads touch heaven,

It was my hint to speak. Such was my process.

And the Cannibals that each other eat,

The Anthropophagi, and men whose heads

Grew beneath their shoulders. These things to hear

Would Desdemona seriously incline;

But still the house affairs would draw her thence ;

Which ever as she could with haste dispatch,

She’d come again, and with greedy ear

Devour up my discourse. Which I observing,

Took once a pliant hour, and found good means

To draw from her a prayer of earnest heart

That I would all my pilgrimage dilate,

Whereof by parcels she had something heard,

But not intentively. I did consent,

And often did beguile her of her tears

When I did speak of some distressful stroke

That my youth suffered. My story being done,

She gave me for my pains a world of kisses.

She swore in faith’twas strange, ‘twas passing strange;

‘Twas pitiful, ‘twas wondrous pitiful.

She wished she had not heard it ;yet she wished

That heaven had made her such a man. She thanked me,

And bade me, if I had a friend that loved her,

I should but teach him how to tell my story,

And that would woo her. Upon this hint I spake.

She loved me for the dangers I had passed,

And I loved her that she did pity them.

This only is the witchcraft I have used.

Here comes the lady. Let her witness it.

So, we conclude that origin, colour of skin, religion, language and social status have not been an obstacle for Othello to reach the centres of knowledge and excellence in Europe and become an important member of society there and this is a fine example of the cultural interaction that existed then between Europe, as a whole, and the Southern Mediterranean.

Inter-Cultural Interaction

Lyautey, The Great cCommunicator

At the beginning of the 19th century, the European nations’ appetite for more colonies, raw materials and markets grew stronger and especially among France, Britain, Germany, Italy and Spain who expressed a special colonial interest vis à vis the North African countries of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya.

In 1830, the French occupied Algiers and in 1847 they won complete control of the rest of the country except for the Saharan area which was subdued between 1900 and 1909.xliii In the French colonial terminology, Algeria was an integral part of France: Algérie française. As for Tunisia it was occupied by the French in 1881 and despite Italy’s opposition, they went ahead and established a protectorate under a French resident general with the bey as titular ruler.xliv Italy took control of Libya in 1911 and began its development as a colony in 1930 when they brought 20,000 colonists and settlers from the home country. xlv Morocco, which remained free of Ottoman influence and control, was finally subdued in 1912 by European powers and as such French and Spanish protectorates were established.

Both in Morocco and in Tunisia, the French established a European type of administration and government alongside the traditional system of rule based on the Islamic model, whereas in Algeria they only acknowledged the French system on the ground that Algeria is French and should be ruled by the French legal system only.

In Morocco the cohabitation between the traditional Moroccan system and the modern European one was initiated by the first French resident general Lyauteyxlvi and was instrumental in the emergence of modern Morocco. Lyautey was an excellent cultural communicator, he was respectful of the local traditions and all his efforts and those of his administration were geared towards the modernisation of the country without destroying, in the process, its culture. He had an incredible sense of adaptation to places and situations as pointed out by Alan Scham: xlvii

Lyautey had qualities that appealed to the Moroccan, Berber or Arab. He was a man of decision, integrity, and justice; he liked a good show; he was a superb horseman, and a born leader. One of his greatest qualities was that he could adapt himself to new situations without restricting himself to any specific formula in his administration of Morocco: «Everything depends upon the time and place. You tried one method in Indochina and it succeeded; that does not mean it is going to work in Madagascar or Morocco. What is suitable for some is not necessarily suitable for others: climate, religion, race, history- so many elements can change the problem.»

Lyautey was a man with the distinctive ability, that only few people possess, to respect the “other” in all aspects of his “otherness”, in all humility. In his legendary generosity of soul and nobility of origin, he taught people of different languages, cultures and faiths to engage in inter-cultural communication for a better understanding of each other and undoubtedly this is one of the valuable secrets of his success in leading Morocco, with extreme care and serenity, to modernity and development.

Alan Scham xlviii points out in this respect that Lyautey did not sincerely wish any form of Frenchification of Moroccans:

“Lyautey’s distinction, aside from his exceptional force of character, was that, unlike most contemporary French colonial officials, he was not an «assimilationist.» He felt a sincere respect for Moroccan civilization, and did not think it either possible or desirable simply to Frenchify the Moroccans. He hoped that Frenchmen and Moroccans would be able to collaborate in the necessary modernisation of Morocco without destroying intrinsically valuable Moroccan traditions and characteristics. He wanted the Protectorate to be a genuine protectorate, not a disguised colonial administration.”

Mohammed V (1913-1961), xlix monarch of Morocco (1927-1953; 1956-1961), was very much an admirer of Lyautey and his work in this country, for his respect of the traditions and his great ability to convince and communicate with people in their own beliefs and cultural symbols. During a visit to the Colonial Exhibition at Vincennes in France in 1931, Mohammed V, then a young monarch, paid a unique tribute to the man:

“Coming to admire the Colonial Exhibition, which is a wonderful achievement of your genius, it is Our special pleasure on this occasion to convey Our greeting to the great Frenchman who was able to safeguard Morocco’s ancient traditions, morals, and customs, while at the same time introducing the spirit of modern organization, without which no country could exist today.

Can we in fact forget that upon your arrival in Morocco, the Sherifian Empire was threatened with ultimate ruin? Her institutions, her arts, her faltering administration- all were calling for an organizer, a renovator of your ability to put her back on the right path, to direct her toward her destiny. By taking into consideration the susceptibilities of her inhabitants, by respecting their beliefs and customs, you have drawn them to la France protectrice by your noble qualities of heart and by the grandeur of your soul.”

Migration

As early as 1920s, North African populations started to move north to work or study in Europe. At the initial stage this movement involved individuals only, but, with time, families and dependents joined the movement and communities started to form in the main capitals of Europe, as well as, in the main industrial centers. After World War II , in the wake of the Marshall plan, Europe in full frenzy of reconstruction encouraged thousands of unqualified workers to move north to work in construction sites, coal mines and assembly lines. This migratory movement, considered one of the most important of the century was at the origin of a new cultural reality: the establishment of migrant communities’ ghettos.

Initially, the migrants in their majority illiterate and coming from poor rural areas went to the bled nsara l with the intention of making as much money as possible, in the shortest time possible and return home to build a house and start a business. However, after the initial euphoria, this goal proved quite difficult to achieve and around 1975, as the European governments decided to put an end to legal migration, the migrants were allowed to bring their families and settle down with them. With the arrival of the families, new cultural challenges appeared, having to do especially with the education of children: in what culture to educate them Arab-Islamic tradition or Christian / secular European system? The former was difficult and costly to set up; the latter was readily available but was alienating and contrary to religious teachings.

With time the migrants had children born to them in the countries of migration and brought up in its culture; generally speaking they are bicultural and bilingual by belonging to both countries i.e. country of origin of parents and country of residence, but they are also confused and torn apart between two allegiances. To solve this thorny problem, the children of migrants born in the country of migration, referred to themselves as beur li and their culture as culture beur.

In this regard Paul Balta,lii argues quite rightly that the beurs and beurettes (feminine form for beur) are considered to be pernicious vehicles of western way of life and thought. But in spite of this recrimination, it is a well-known fact that the beur generation has achieved success in various fields: show biz, theatre, cinema, literature, etc.: liii

«Non pas que la situation de la génération « beur » soit idyllique et qu’elle ne connaisse pas de nombreux problèmes (délinquance juvenile, difficultés d’insertion dans la société d’accueil pour les moins favorisés, les plus fragiles, les plus déchirés) mais remportent aussi d’indéniables succès dans des domaines très divers, elle s’affirment de jour en jour à travers ses représentants. Comédiens : Isabelle Adjani, Nadia Samir, Souad Amidou, Lydia Maoudj, Smain, Kader Boukhanef, Mouss, Hakim Ghanem, Rachid Ferrache, Pascal Kelaf, Hammou Graia, Farid Chopel, Karim Allaoui, pour n’en citer que quelques-uns ; écrivains : Farida Belghoul, Leila Sebbar, Leila Houari, Nacer Kettane, Akil Tadjer, Azouz Begag, Jean-luc Yacine, etc. ; chanteurs et musiciens mais aussi peintres, graveurs, sculpteurs, journalistes , hommes et femmes de radio et de télévision, chercheurs, entrepreneurs… »

This migrant community proved to be a formidable instrument in inter-cultural communication and exchange between North Africa and Europe and, indeed, thanks to them, such foods as tagine, couscous, harira, mechoui, etc. became popular in all of Europe and especially in France. The migrants also succeeded in imposing their music and educating the western ear to accept it and enjoy its melodies. As such in the late 70s and early 80s, the Berber singer Idir took France and Europe by the storm with his album “vava inou va” of Kabyle melodies, Cheb Khaled followed in his steps and brought to fame world-wide the Algerian Arab rai music. His song “ddi ddi” was the first Arab single to make it to the top 40, an important parameter of fame and appreciation in the field of European show business.

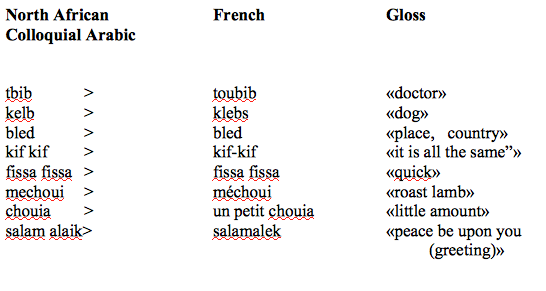

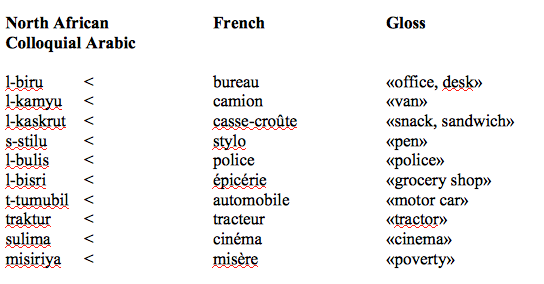

Because of contact between France and North Africa through colonization and migration, both French and colloquial Arabic borrowed from each other scores of words as shown below:

It must be said that inter-cultural communication and exchange between North Africa and Europe is bound to increase in quantity and quality at the beginning of the next millennium with the implementation of the partnership agreement between Morocco and Europe and Tunisia and Europe.

Conclusion

We have attempted to show in this paper that inter-cultural communication and exchange between Europe and North Africa is a social and cultural phenomenon that has existed as far back as there were contacts between the two regions.

We have shown, also, that this form of interaction has always manifested itself directly through the following channels:

- language;

- literature;

- migration;

- commerce;

- colonization, etc.

Irrespective of the difference of way of life, religious beliefs, patterns of thinking and materiel wealth.

Similarly, we have argued that xenophobia, racism, and ethnocentrism have never been a serious hindrance to inter-cultural communication and exchange.

In conclusion, we believe that inter-cultural interaction will continue to grow between Europe and North Africa during the next millennium as the two sides initiate a new phase of partnership in the era of globalisation of exchanges.

You can follow Professor Mohamed Chtatou on Twitter: @Ayurinu

END NOTES:

i. Cf. Huntington, S.P. « The Clash of Civilizations ?». Foreign Affairs 72, no. 3 (Summer 1993) ; cf. also Lewis, L. « The Roots of Muslim Rage ». Atlantic Monthly, September 1996.

ii. Cf. Roberson, B.A. « Islam and Europe : an Enigma or a myth ». The Middle East Journal 48, no. 2 (Spring 1994)

iii. Personal communication

iv. Webster’s New World Dictionary of the American Language (second college edition) defines culture as : « the ideas, customs, skills, arts, etc. of a given people in a given period. » ; as for The Columbia Viking Desk Encyclopaedia (second edition), it defines culture in the following terms : « … the way of life of a society, without implication of refinement or advanced Knowledge. Culture is historically transmitted, primarily through language, and is the attribute that most distinguishes man from the animals. »

v. Cf. Guernier, E. 1950. La Berbérie, l’Islam et la France. Vol. 1. Paris : Editions de l’Union Française. P. 98.

vi. Cf. Albertini, E. 1937. L’Afrique Romaine. Alger. P. 34 :

« L’aménagement hydraulique a été la partie la plus importante de l’oeuvre romaine en Afrique. »

vii. Cf. Carcopino, J. 1939. La vie quotidienne à Rome. Paris : Hachette.

viii. Cf. Hammouda, A. 1988 . La Victime et ses masques. Paris: Seuil, for ample discussion of this unique phenomenon which is traced back to ancient Greece and ancient Rome.

ix. http://thequietus.com/articles/07488-master-musicians-of-jajouka-joujouka-glastonbury

x. Pan, in Greek religion, pastoral god of fertility. Worshipped chiefly in Arcadia . He was portrayed as merry, ugly man with horns, beard, tail, and goat’s feet. All his myths deal with amorous affairs : e.g. , his unsuccessful pursuit of the nymph Syrinx, who became a reed, which Pan plays in memory of her. He was later identified with Greek Dionysus and Roman Faunus, both gods of fertility.

xi. Oboe-like pipe.

xii. baraka: divine blessing .

xiii. bel : a large and resonant drum played by beating two wooden sticks on either of the skin covered sides of the instrument

xiv. http://www.ircam.ma/sites/default/files/doc/revueasing/mohamed_chtatou_asinag2fr.pdf

xv. Cf. Crapanzano, V. 1973. The Hamadsha : A Study in Moroccan Ethnopsychiatry. Berkeley: University of California Press.

xvi. Cf. Lane-Pool, S. 1887 (1984). The Moors in Spain. London : Darf Publishers Ltd. P. 13 xvii. Ibid. pp vii-viii.

xviii. Op. cit. p. 24.

xix. Cf. Taha, A.D. 1989. The Muslim Conquest and Settlement of North Africa and Spain. London: Routledge . P. 42 « There is clear and unequivocal testimony from every Visigothic edict concerning the Jews that they were persecuted and savagely treated. »

xx. Cf. The moors in Spain op. cit.

xxi. Cf. Muir, K.1957. Shakespeare’s Sources : Vol. I, « Comedies and Tragedies ». London: Methuen &Co., Ltd. The first volume on comedies and tragedies, attempts to ascertain what books were Shakespeare’s sources, and what use he made of them.

xxii. Cf. Kernan, A. 1963. « Introduction » in Othello. New York, New York : New American Library

xxiii. Cf. Othello, III iii, 450-457.

xxiv. Ibid, I, iii, 390-393.

xxv. Ibid, V, ii, 159-161.

xxvi. Ibid, I , iii, 94-103.

xxvii. Ibid, I, iii , 103-106.

xxviii. Ibid, I , iii, 60-64.

xxix. Ibid, I , iii, 108-111.

xxx. Ibid, I, iii, 113-114.

xxxi. Ibid, I , iii, 342-354

xxxii. Cf. Webster, M. 1966. Shakespeare without Tears. New York, New York: Premier Book. P. 178.

xxxiii. New World Dictionary (Second College Edition) 1976 , defines the term Moor as 1. a member of a Moslem people of mixed Arab and Berber descent living in NW Africa 2. a member of a group of this people that invaded and occupied Spain in the 8th century AD. P..924.

The Columbia-Viking Desk Encyclopedia( Second Edition), 1966. Moors, nomadic people of N Africa, once inhabitants of Mauretania. Converted to Islam in 8th cent. , and became fanatic Moslems. Crossed into Spain in 711 and easily overran crumbling Visigothic kingdom of RODERICK. Spreading beyond Pyranees into France, they were turned back at Tours by CHARLES MARTEL 732. Moors made TOLEDO, CORDOBA and SEVILLE centers of learning and culture, but never had a strong central government. Christian reconquest of Spain began with recovery of Toledo (1085) by Alfonso VI, king of Leon and Castile, and ended with recovery of Granada by Ferdinand and Isabella in1492. Moors were driven from Spain, leaving contributions to W Europe in art, architecture, medicine, science and learning. P 1207-1208.

xxxiv. Barbary States, term used for the N African states of TRIPOLITANIA, TUNISIA, and ALGERIA (and usually also MOROCCO), which were semi-independent under Turkish rule from 16th cent. onward. Rulers derived revenue from large-scale piracy on Mediterranean shipping. European powers launched punitive expeditions against them but largely relied on payment of tribute as means of protection. The U.S. joined in this system. The insult offered by the dey of Algiers to William BAINBRIDGE, taking U.S. tribute to Algiers, led to the TRIPOLITAN WAR. French capture of Algiers (1830) marked the end of piracy in the region. (Cf. The Columbia-Viking Desk Encyclopaedia, 1966. P. 150.)

xxxv. Cf. Othello, I, iii, 178-187.

xxxvi. Ibid, I, iii, 47.

xxxvii. Ibid, I, iii, 48.

xxxviii. Ibid, I, iii, 127-169.

xxxix. Cf. The Columbia-Viking Desk Encyclopaedia, p , 56.

xl. Ibid, p. 1862.

xli. Ibid, p. 1025.

xlii. bid, pp. 1068-1069, Lyautey, Louis Hubert Gonzalve, 1854-1934, marshal of France. As French resident general in Morocco (1912-16,1917-25), he proved an extremely able colonial administrator and may be said to have created modern Morocco.

xliii. Cf. Scham, A. 1970. Lyautey in Morocco. Berkeley : University of California Press. P. 17.

xliv. Ibid, p. 192.

xlv. bid, p. 204.

xlci. bled nsara means literally « the land of the Christians », it is also used to refer to Europe.

xlvii. beur finds its origin in rbeur French slang for arabe, and it refers generally to second generation Arabs in France.

xlviii. Cf. Balta, P. 1990. Le Grand Maghreb : Des indépendances à l’an 2000. Paris : La Découverte. P. 285

xlix. Ibid, p. 286.