Tighter Marine Fuel Sulfur Limits Will Spark Changes By Both Refiners And Vessel Operators – Analysis

By EIA

The sulfur content of transportation fuels has been declining for many years due to increasingly stringent regulations. In the United States, federal and state regulations limit the amount of sulfur present in motor gasoline, diesel fuel, and heating oil. New international regulations limiting sulfur in fuels for ocean-going vessels, set to take effect in 2020, have further implications for both refiners and vessel operators at a time of high uncertainty in future crude oil prices, which will be a major factor in their decisions.

Bunker fuel—the fuel typically used in large ocean-going vessels—is a mixture of petroleum-based oils. Residual oil—the long-chain hydrocarbons remaining after lighter and shorter hydrocarbon fractions such as gasoline and diesel have been separated from crude oil—currently makes up the largest component of bunker fuel. The sulfur content of crude oil tends to be more concentrated in heavier hydrocarbon molecules, with heavier petroleum products such as residual oil having higher sulfur content than lighter ones like gasoline and diesel.

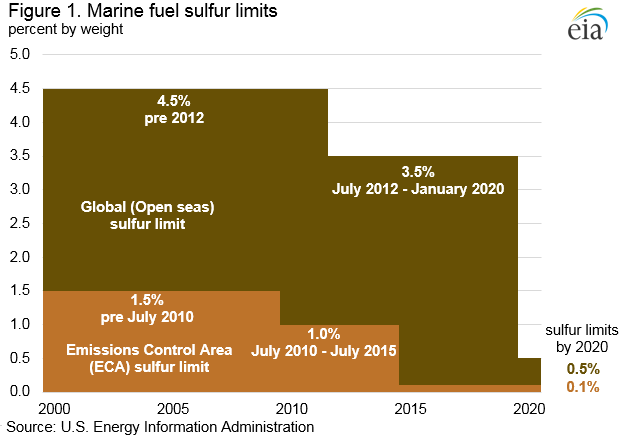

The International Maritime Organization (IMO), the 171-member state United Nations agency that sets standards for marine fuels, decided in October to move forward with a plan to reduce the maximum amount of sulfur and other pollutants present in marine fuels used on the open seas from 3.5% by weight to 0.5% by weight by 2020. This decision follows several other marine fuel regulations limiting sulfur content, such as the implementation of Emissions Control Area (ECA) requirements in coastal waters and specific sea-lanes in North America and Europe, where the maximum sulfur content of fuels was limited to 0.1% by weight starting in July 2015 (Figure 1).

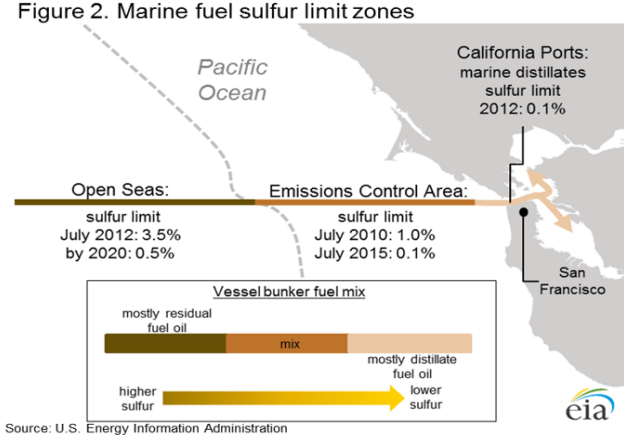

Additionally, the state of California and the European Union have regulations on the sulfur content of marine fuels, and the types of fuel used when ships are at dock, waiting to dock, or are maneuvering within port. For example, a vessel approaching the port of San Francisco may have to change its fuel mix twice: once when going from the open seas higher-sulfur fuel of mostly residual oil, to an ECA compliant lower-sulfur fuel mix, and again to a marine diesel fuel compliant with California’s ocean-going vessel regulations for use within ports (Figure 2).

The IMO sulfur limits that take effect in 2020 will affect the fuel used in the open seas, the largest portion of the approximately 3.9 million barrels per day of global marine fuel use, according to the International Energy Agency, presenting several challenges for both refiners and shippers.

The first challenge for refiners is to increase the supply of lower-sulfur blendstocks to the bunker fuel market. Refiners have several potential paths. One approach is to divert more low sulfur distillates into the bunker fuel market. Another option would be to use low sulfur intermediate refinery feedstocks in bunker blends. In both cases, care is required to assure that new fuels continue to meet specifications for use in marine engines.

A second challenge for refiners is what to do with the high sulfur residual oil that can no longer be blended into bunker fuel. Adding capacity to desulfurize residual oil is one option, but the economics do not currently appear to be attractive. An alternative strategy is to build or expand refinery units that take heavy hydrocarbons, such as residual oil, and upgrade them into lighter, more valuable products, but this would require large investments. In either of these cases, refineries would be faced with investments and costs that are acceptable only if there is certainty of future demand from the shipping industry.

Vessel operators also have several choices for compliance with the new IMO sulfur limits. For example, IMO regulations allow for the installation of scrubbers, which remove pollutants from ships exhaust, allowing them to continue to use higher-sulfur fuels. Some ship owners that operate primarily in coastal areas, such as cruise lines and ferries, opted to install scrubbers on their vessels as the new ECA regulations came into force. The possibility of widespread scrubber installations, which would allow for continued use of higher sulfur residual oils, could make refiners hesitant about making large investments to build refining units capable of upgrading the residual oils.

Ships also have the option of switching to new lower sulfur blends or to non-petroleum based fuels. Some newer ships and some currently being built have engines that would allow them to use liquefied natural gas (LNG) rather than petroleum-based products. However, the infrastructure to support use of LNG as a shipping fuel is currently limited in both scale and availability.

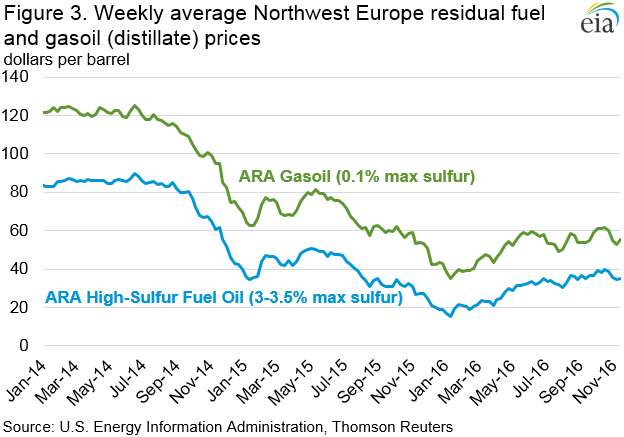

Vessel operators and shippers will also likely be faced with the higher costs as the sulfur content in marine fuels decreases and the role of distillate in the bunker fuel market increases. An example of the price difference between fuels can be observed at the refining and trading hub in Northwest Europe, known as the ARA, collectively the cities Amsterdam and Rotterdam, in the Netherlands and Antwerp, in Belgium. Prices for low sulfur gasoil, a type of distillate, in the ARA has averaged over $20 per barrel more than high sulfur fuel oil (residual oil for use as a fuel) to date in 2016. Fuel blends used to meet the new IMO regulations are likely to price somewhere in between these two fuels (Figure 3).

U.S. average regular gasoline and diesel retail prices decline

The U.S. average regular gasoline retail price dropped three cents from the previous week to $2.16 per gallon on November 21, up six cents from the same time last year. The Gulf Coast price fell six cents to $1.92 per gallon, while the West Coast, Rocky Mountain, and East Coast prices each fell five cents to $2.59 per gallon, $2.19 per gallon, and $2.17 per gallon, respectively. The Midwest price rose two cents to $2.01 per gallon.

The U.S. average diesel fuel price dropped two cents to $2.42 per gallon, down two cents from the same time last year. The Rocky Mountain price fell four cents to $2.46 per gallon, while the West Coast and Midwest prices each fell three cents to $2.73 per gallon and $2.36 per gallon, respectively. The Gulf Coast price dipped two cents to $2.30 per gallon, and the East Coast price fell a penny to $2.44 per gallon.

Propane inventories gain

U.S. propane stocks increased by 1.8 million barrels last week to 102.7 million barrels as of November 18, 2016, 3.5 million barrels (3.3%) lower than a year ago. Gulf Coast and Rocky Mountain/West Coast inventories increased by 1.7 million barrels and 0.1 million barrels, respectively, while East Coast and Midwest inventories remained virtually unchanged. Propylene non-fuel-use inventories represented 4.0% of total propane inventories.

Residential heating oil price unchanged while residential propane price increases

As of November 21, 2016, residential heating oil prices averaged around $2.38 per gallon, virtually unchanged from last week and less than one cent per gallon higher than last year at this time. The average wholesale heating oil price is $1.55 per gallon, nearly eight cents per gallon higher than last week and 13 cents per gallon more than a year ago.

Residential propane prices averaged nearly $2.06 per gallon, one cent per gallon more than last week and almost 11 cents per gallon more than one year ago. Wholesale propane prices averaged $0.62 per gallon, about the same price as last week but 13 cents per gallon more than last year’s price.