Tibet Returns As Fulcrum Point Between US And China – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

Decades after the US pushed the Tibetan resistance movement under the bus, in its bid to befriend Beijing, Washington seems to have developed some remorse. But in reality, what has happened is that the geopolitical world has taken a complete circle.

By Manoj Joshi

As part of the continuing US pressure on China, the US Congress has passed a bill to step up US support to Tibetans. The Tibetan Policy and Support Act (TPSA) has been passed by the two houses of Congress as an amendment to the $1.4 trillion government spending bill and the $900 billion COVID-19 relief package.

The Act will bring on economic and visa sanctions on any Chinese officials who interfere with the succession of the Dalai Lama and will require Beijing to allow the US to establish a consulate in Lhasa, before it can open any more consulates in the US.

The Dharamshala-based Central Tibetan Administration is ecstatic, with Lobsang Sangay, its President (Sikyong), declaring this to be a “momentous landmark for the Tibetan people.”

Recently, Sangay, who was educated at Harvard University and is an American national, was invited to the White House where he met with Robert Destro, the newly appointed US special coordinator for Tibetan issues.

Decades after the US pushed the Tibetan resistance movement under the bus, in its bid to befriend Beijing, Washington seems to have developed some remorse. But in reality, what has happened is that the geopolitical world has taken a complete circle.

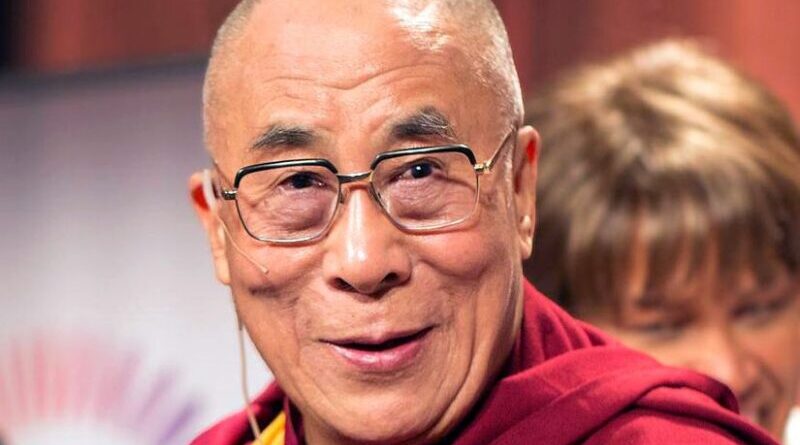

Modern politics should not really be concerning themselves with issues like the reincarnation of a high lama. But the Dalai Lama belongs to a category of his own. Ever since he fled China and took up exile in India, he has symbolised the Tibetan struggle against Chinese oppression. His personality and message have reverberated through the world and despite strenuous efforts by Beijing, he is still received in the capitals of the world with respect and, by his followers, with adoration.

The Dalai Lama himself has been clear about the need to pursue the Tibetan struggle in a non-violent fashion and has repeatedly made it clear that what he seeks is greater autonomy from China, rather than independence. But Beijing refuses to buy this and terms him “splittist.”

Reincarnations and reincarnates

Tibetan Buddhists, like many Hindus believe that everyone goes through a cycle of re-incarnation which is decided on by your karma. But high lamas, or Tulkus, of whom the Dalai Lama, a reincarnation of the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, is the senior most, can determine when and where they will be reborn. Usually, the high lama confides the details of his new reincarnation with some chosen acolytes who then set about finding him.

As he ages, the present Dalai Lama has thought a great deal about the issue. He has been worried that the process of reincarnation will be hijacked by politics. On one hand he has wondered whether it was time that he does not reincarnate at all. On the other, he has expressed an interest in working out clear-cut guidelines to ensure that there “is no room for doubt or deception” in the process. This is aimed at the Chinese who will almost certainly set up their own successor Dalai Lama when this one passes.

This is what worries the Dalai Lama. A Chinese “capture” of the Dalai Lama would result in a discrediting of the high office. As the Dalai Lama said in his statement, the Chinese Communists “who explicitly reject even the idea of past and future lives,” leave alone the concept of Tulkus, should hardly meddle in such areas. The Chinese believe that the final authority in appointing a high lama belongs to them, sanctioned by history and custom. In 2007, the State Administration for Religious Affairs in China had decreed that reincarnations must be approved by the government or they would be deemed invalid.

Earlier in 1995, the Chinese had reinstated a Qing dynasty rite that mandated that prominent Tibetan monks be identified through a draw of lots from a golden urn. In May that year, the Chinese authorities had negated the Dalai Lama’s selection of six-year old Gedhun Choekyi Nyima as the reincarnation of the 10th Panchen Lama, and installed Gyaincain Norbu in his place. Nyima and his family have not been seen again. Traditionally, the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama have played the role of each other’s preceptors and the Dalai Lama’s choice was based on the tenets of Tibetan tradition.

However, the Chinese reverted to a process begun at the instance of the Manchu Emperor in the late-18th century to confirm rimpoches, lamas, and other high authorities of Tibetan Buddhism. The rules were established after a Qing army helped the 7th Dalai Lama to re-establish his authority and also extend Chinese authority over Nepal in 1720. According to the Manchu law, names of candidates for the top Lamas, including the Dalai and the Panchen were put in urns in temples in Lhasa and Beijing and a draw of lots decided the candidate. Though this practice was only fitfully carried out, the Chinese now claim that this has been a practice of Tibetan Buddhism.

History

The People’s Republic of China claims itself to be the successor “central Administration of China” whose history goes back millennia. Further, it sees no contradiction in a Marxist-Leninist state claiming the imperial borders, or for that matter, the imperial culture of its predecessors. So, in this case, the Chinese have built their case with their own interpretation of the relationship between the Dalai Lama and the Chinese empires which in two important cases were not Han Chinese.

Tibet was first conquered by the Mongols, who also conquered China in the 13th century, and many Mongol kings viewed Tibetan Lamas as religious preceptors. The Ming Empire that succeeded the Mongols in the 14th century left Tibet alone, but Tibetan religious leaders were welcomed at the court.

At this time Tibet was dominated by independent Mongol kings who patronised the Dalai and, indeed, the fourth Dalai Lama was reincarnated in the family of a powerful Mongol chief Altan Khan. The next Dalai Lama, the Great Fift (1617-1682), was both the religious and temporal ruler of the country. Historian Sam van Shaik has noted that “though many modern Chinese historians have taken his visit [to Beijing to meet the emperor] as marking the submission of the Dalai Lama’s government to China, such an interpretation is hardly borne out either by the Tibetan or Chinese records of the time.”

The reality is that China, itself never viewed itself as China till the 20th century. The relationship of its various empires with other regions were complex and not comparable to modern practice. Indeed, the British deserve a lot of blame for inventing the concept of “suzerainty,” which was some kind of semi-sovereignty, to legitimise Chinese rule over Tibet to serve their own imperial goals.

The future

At various points in time in the last three decades the Chinese and Tibetans have made efforts to negotiate a settlement. But as China ascended the world order beginning 2008, it began to take a hard line on Tibet and terminated the negotiations. In 2013, Yu Zhensheng, a ranking Politburo Standing Committee member in charge of Tibet had categorically declared that the Dalai Lama’s call for autonomy was against the Chinese constitution. Yu added that until the Dalai Lama “publicly announces that Tibet is an inalienable part of China since ancient time, gives up the stance of ‘Tibet independence’ … can his relations with the Communist Party of China Central Committee possibly be improved.”

As of this point the Chinese control over Tibet is firm. Indeed, going by the recent remarks of President Xi Jinping, China would now like to ‘Sinicize’ Tibetan Buddhism. Just what that means is not clear. But at a meeting on Tibet’s future governance, Xi called for the authorities to build an “impregnable fortress” to maintain stability there and for a struggle against the forces of “splittism.” The Chinese are seeking to come up with “re-educational” campaigns and programmes to push Tibetan Buddhists in the desired direction. Molding Tibetan Buddhism to conform to the CPC’s beliefs is not unusual. China, especially under Xi Jinping, insists that every faith, Buddhist, Daoist, Christian or Islam, must conform to the CPC’s values. Notwithstanding decades of repression and campaigns against “splittism” and Buddhism, Tibetans remain loyal to their culture and refuse to identify with China and the Han race as their premier identity. This is not very different from the situation in Xinjiang. But the CPC insists on trying to merge them all to create “one nation.”

To a large degree, China’s India policy has been shaped by its interests in Tibet. The Chinese don’t want to accept the fact that Tibet and India have had traditional relations that neighbours have. The most sacred sites of Hinduism, Kailash and Mansarovar, are in Tibet and, till the 1950s, a great deal of traffic, even between China and Tibet was through the port of Kolkata (then Calcutta).

The fact that the Dalai Lama has taken refuge in India has deepened the Chinese unease about the role of New Delhi, not just in ongoing affairs, but also on his future re-incarnation plans. In part this is what drives the Chinese demand that the minimum condition for a border settlement would be India conceding Tawang, with its famous monastery, built in the seventeenth century at the instance of the Great Fifth Dalai Lama.

With growing tensions between China and the US, Tibet is re-emerging as a fulcrum of new Cold War politics. India has in recent years tried to play the Tibet card, but it lacks the heft to make effective use of it. But the US is a different ball game, both the Chinese and the Tibetans know this.

Finally, a word of caution. It has been the Tibetans who have paid the heaviest price for the contest between China and the US. Hopefully this time their fortunes will fare better.