Tech Becomes CCP’s New Frontier For Spreading Its Influence – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

By Kalpit A Mankikar

While the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) is getting more and more determined to shape global discourse in its favour, it’s approach towards the same is getting sophisticated.

Global social media platforms have become the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) arena to spread its influence, and dox critics. The CCP is enlisting private firms to produce content that can be used in influence operations, in what it terms as “public opinion management”, revealed an international media outlet. While the Party deploys global social media platforms to spread its propaganda, they are out of bounds for ordinary residents living in China.

Social media seems to have particularly come in handy for the CCP in the post-truth world where facts and empirical evidence have less heft in moulding mass opinion than social media narratives, which appeal to emotion. A case in point being the claim by a Swiss biologist that the US government was impeding efforts of the World Health Organization to zero in on the starting point of the coronavirus pandemic. While the Swiss embassy in China clarified that the said biologist simply did not exist, it did not stop Chinese state-controlled media from amplifying the fantastic claims.

The CCP deploys the concept of “United Front” to co-opt and offset sources of resistance to its programmes. The CCP’s United Front Work Department—the unit tasked with coordinating different types of influence operations—concentrated on tackling potential opposition groups internally. Early in 2021, the unit updated guidelines for conducting domestic and overseas influence operations. The new regulations, which bring up to date the 2015 manual, point to the fact that United Front activities have expanded in scope. The new directives elucidate in detail the importance of providing “guidance” to Chinese returning from abroad and those based overseas, including their families in China. In a first, they lay out the United Front’s focus on “new social classes,” which include media outlets, knowledge workers, and other highly-skilled Chinese staffers of foreign-invested enterprises and social organisations.

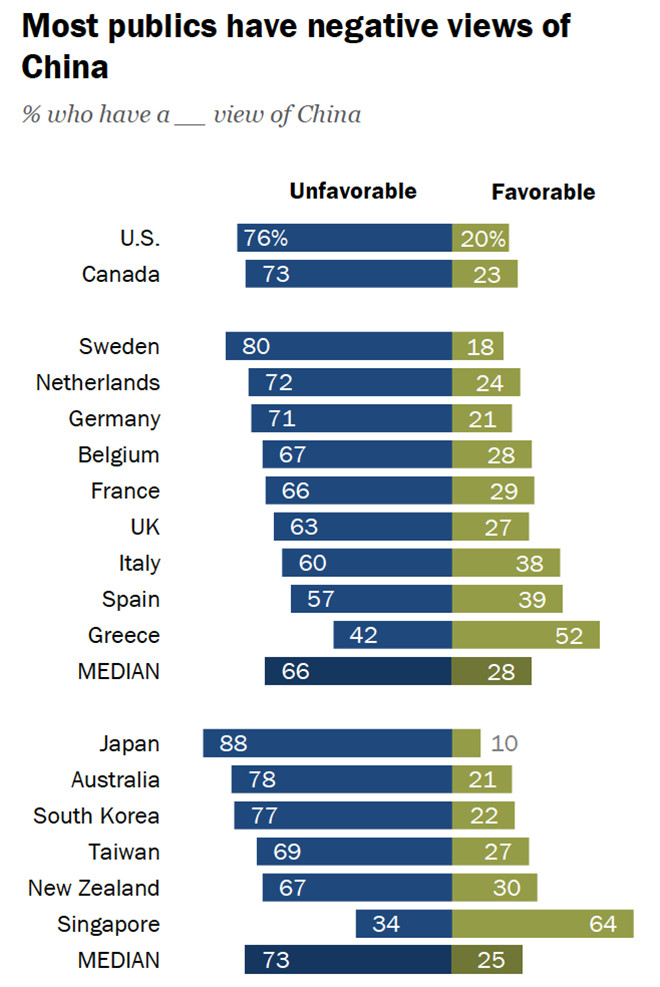

Since the onset of the pandemic, China’s relations with many important global powers have deteriorated. The CCP has got flak for human rights abuses against the Uyghur minority group in its Xinjiang province and the relentless crackdown on activists advocating greater freedoms in Hong Kong, amongst other issues. It is also combating American efforts to broaden investigations into whether or not COVID-19 originated from a research facility on the mainland. A survey by Pew Research Center across 17 nations published in June 2021 revealed that its citizens have developed unfavourable views of China since the pandemic broke out (see graphic).

China’s diplomatic corps has become increasingly vociferous in recent years, and gone to the extent of upbraiding governments who take a mildly critical position.

The strategy touted as “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy—named a blockbuster movie in which Chinese special forces challenge American soldiers of fortune.

Amidst these developments, Xi Jinping has emphasised that China must tell its story in a positive way and that it is imperative to strike friendships and constantly expand the circle of friends with respect to international public opinion. In this endeavour, the narrative-setting through cyberspace is a key tool.

Xi had realised the potential of the internet as a propaganda tool early on. Through China’s popular mobile messaging app and micro-blogging site, WeChat and Weibo, Xi promoted his campaign against corruption, and to build a personal following. Notwithstanding the ban of Facebook in China, the CCP used the platform to promote Xi’s profile during his state visits to other nations.

“The internet has become the chief battleground for public opinion struggle,” Xi declared at the National Propaganda and Ideology Work Conference in 2013. He then moved to quickly consolidate the institutions regulating cyberspace in China. He assumed charge of the Central Internet Security and Informationised Leading Group a year later, and reconstituted the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC). The leading group had been previously headed by China’s premier, and the changes gave Xi greater control over the nation’s internet policy. Xi’s pick to head the CAC, Lu Wei, who had worked as a journalist with the state-run Xinhua, had argued in an essay in the CCP’s journal ‘Qiushi’ (which means seeking truth) that the Party must have a grip on information technology. He stated that there was “no economic, financial or national security without information security.”

Amazon—one of the Big Five companies in the US info-tech sector—manipulated ratings in its online store for a book authored by Xi after a nudge from the CCP.

The CCP conceives cyberspace as an “internet civilisation”—where the civilised forces are arrayed against those with selfish motives who want to spread “harmful” information. CCP’s theorist in charge of propaganda Liu Yunshan had argued that, “The nation’s approach towards internet development would prioritise fortifying of online public opinion guidance, and the consolidation of positive mainstream public opinion.” Domestically, China has an army of cyber-warriors to maintain its writ on information flows, titled ‘internet public opinion analysts’. These personnel are deployed across the government’s propaganda units, private firms, and media outlets. An examination of China’s social media revealed that the Party activity shapes internet discourse, putting out as many as 488 million online posts each year, and deleting those that are unfavourable. Besides, China’s Big Tech have ‘red genes’; Baidu’s Robin Li and Qihoo 360 Technology (internet security services provider) Zhou Hongyi are members of the advisory body Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference.

China presents a large opportunity for Big Tech, and thus, internet doyens seek to be in the CCP’s good books. Amazon—one of the Big Five companies in the US info-tech sector—manipulated ratings in its online store for a book authored by Xi after a nudge from the CCP. Microsoft’s career-networking site, LinkedIn, blocked access to the accounts of Greg Bruno and other journalists for users in China. Bruno, who has documented the conditions of Tibetans, said he was disappointed that a US technology major was “caving into the demands of a foreign government”. US senator Rick Scott red-flagged this appeasement of Communist China in missives to LinkedIn Chief Executive Ryan Roslansky and Microsoft boss Satya Nadella.

Thus, social media, which has been a catalyst for social change in Africa and West Asia by playing its part in enabling the ‘Jasmine Revolution’ and ‘Arab Spring’, has unwittingly or otherwise become instrument for the CCP’s influence operations. Furthermore, the penetration of global media platforms and their use by the CCP to spread its influence pose a huge challenge to democracies across the world. CCP’s subversion of the internet domestically in China, has now emboldened it to foist its model elsewhere. Social media has become a main pillar of public participation in democracies, it also plays the role of barometer of public opinion. In recent times, when the concept of democracy is being hotly debated in different parts of the world, democracies must highlight China’s double standards in use of social media platforms in democracies, and the CCP’s domestic legislation that criminalise spreading rumors that “undermine economic and social order”, and mandate its own social media platforms to republish news reports from registered news media.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s).